Editor’s note: I am happy to welcome a guest contributor who will be known to many of you. Professor Emeritus Robert Shipley was Associate Director of the School of Planning, University of Waterloo and Director of the Heritage Resources Centre until his retirement in 2016. He was a Research Fellow at Oxford Brookes University, England and is recognized as a leading international expert on culture, heritage and tourism and the economics of heritage development. He is a former VP of the Canadian Association of Heritage Professionals and recipient of the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal.

In the last months, by way of Bill 108 and a new draft regulation, changes are being made to the Ontario Heritage Act and the language of heritage designation in particular. This made me shake my head. It doesn’t matter what the details are but it raises the question, what has become of our corporate memory? Is there anyone in or near the Ministry of Heritage, Sport, Tourism and Culture Industries who knows what took place over the last couple of decades that once took us to the brink of a systematic built heritage conservation culture? Apparently not.

As an elder in the heritage field, all I can do is tell the story and hope that it helps those who now have the torch. They say that it is the victors who get to write the history. In this case, there are no victories, so perhaps it is the last left standing who gets to tell the tale. What I write about here are the undertakings that I think are salient. If others remember things differently, they can tell their own version.

Let’s go back to the latter part of the last century. There had been a slow buildup of interest and enthusiasm for historic conservation from the signing of the World Heritage Convention in 1972, the endowing of the Heritage Canada Foundation (now the National Trust for Canada), and the passing of provincial heritage statutes, including the Ontario Heritage Act in 1974. At the federal level the Parks Canada of the day managed numerous historic sites and undertook some education and outreach. Canada was participating, albeit timidly, in what was a worldwide movement.

At the core of this movement, philosophically, was a three-pronged approach: identify, regulate and fund. Identifying historic properties meant having a sound and objective system of recognizing value. Entrusting this function to trained professionals was the practice in most advanced countries. In Canada, for the most part, it was left to well-meaning amateur advisory committees.

The second component of the conservation philosophy was to regulate properties with historic value. That involved preventing their destruction and having a fair process for managing change. That usually involved the owner submitting plans to a local authority for approval.

Lastly, there was some mechanism for financial assistance. Based on the notion that property owners are giving up some control of their property for the common good, they should therefore be entitled to some level of public funding support.

Why has this not worked in Canada to any satisfactory degree? The straightforward answer is that there has virtually never been a financial incentive for property owners.

Once, however, a golden age almost dawned. In 1996, Hamilton MP Sheila Copps became the Minister of Canadian Heritage in a period when cabinet posts lasted longer than a few months (she held the position until 2003). Ms. Copps was dedicated to bringing Canada into the twenty-first century with regard to heritage conservation. On her watch a career public servant, Peter Frood, was charged with creating the Historic Places Initiative (HPI). Parks Canada, where the expertise in cultural heritage management resided, was an arm of the Environment department. Treasury Board had the money and Revenue Canada the tax levers, so cooperation in Ottawa among departments and agencies was required to make anything work.

Since land use planning and property regulation are provincial responsibilities under the Canadian constitution the federal government had no direct involvement in managing heritage conservation except on federal Crown land. What national government does have is financial resources. The HPI set out to coordinate an effective federal/provincial/territorial approach to heritage and to assist in implementation.

Encouraged by the example of the U.S. federal Historic Tax Credit, a wildly successful program that has leveraged enormous sums of private investment in the rehabilitation of historic buildings, HPI set about to establish the three-pronged strategy. HPI would bring order to historic site identification and description that was, at the time, a dog’s breakfast of different provincial procedures. HPI would also create and promulgate standards and guidelines for conservation practice that could be used across the country. Finally, HPI would rely on good documentation to channel the funding for heritage projects that would probably be in the form of tax incentives, and would use the standards and guidelines to evaluate whether conservation work had been done properly.

All of this work was made somewhat easier because Canada was adopting conservation practices that were well established in other countries and supported by the experience of UNESCO and the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS).

By the early 2000s the Standards & Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places were launched. The new system for documenting sites, called Statements of Significance (SOS), came into use a little later. The advantage of the SOS is that it set up a common format that was adopted by all the provinces, except Ontario where an exact duplicate with slightly different wording was used.

The SOS was designed to be used as the text for municipal by-laws designating properties. An SOS consisted of three parts: an exact description of the property, an outline of the reasons for designation (in Ontario “a statement of cultural heritage value or interest”), and lastly a list of character-defining elements (in Ontario “heritage attributes”). The components for a statement of cultural heritage value or interest were written into Ontario law in 2006 as Regulation 9/06 under the OHA. It states that there are three possible reasons for designation (design value, historic value and contextual value) and each of these has three subsections. Any one or more of these areas of value could be justification for recognition. Character-defining elements or heritage attributes are those aspects of a property the loss of which would detract from its historic nature.

The principle is this: it is not the volume of information about an historic property that counts but the significance of the property and the crafting of language that can be used to make decisions such as funding. Does a property meet the funding criteria and when completed has the work been done properly?

The logo of the Canadian Register of Historic Places

By 2005 the HPI documentation system was in place and the Canadian Register of Historic Places, consisting of all the documented places, was beginning to grow. In Ontario, it was decided to create Statements of Significance (statements of cultural heritage value or interest) for all existing municipally designated properties. The responsibility for the documentation was passed down to municipalities. They already had the responsibility to identify heritage properties but had the least resources.

A modest $2 million was made available to run a pilot program for rehabilitation projects (the Canadian Historic Properties Incentive Fund). A few eligible sites did receive funding (about $15 million in total) and the program showed genuine promise — but in 2006 the government changed and that was the end of the project financing.

The Historic Places Initiative wanted to carry on with the register in hopes that money would eventually flow. However, without the funding incentive, there was little to motivate municipalities to devote time and treasure to updating all their designation by-laws. That was when Parks Canada approached the Heritage Resources Centre (HRC) at the University of Waterloo.

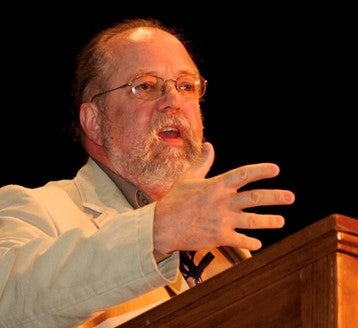

While working for the Parks Canada Historic Places Initiative, members of the Heritage Resources Centre attended conferences, addressed public meetings and conducted workshops around Ontario promoting the work of creating proper documentation for historic sites. These panels were an integral part of their travelling road show.

What was particularly exciting about this program was the dynamic that developed. The process started with the HRC team drafting SOSs, which were then sent back to municipalities to be checked by local staff and/or municipal heritage advisory committees. Once the local people and the HRC team agreed on the text, the files went forward to the Provincial “Registrar” in Toronto. The file might go back and forth until HRC and the Registrar concurred, and then it would be sent to the HPI office at Parks Canada in Ottawa where the reviewing would be repeated. Over time, this process helped to evolve and refine the language used to describe heritage in the Canadian context. Over time, the procedure became smoother and faster. Once everyone had agreed on the SOS text, the site information was posted on the online Canadian Register of Historic Places maintained by Parks Canada.

Members of the Heritage Resources Centre action team at Chiefswood near Six Nations/New Credit Reserve. During the Historic Places Initiative projects the University of Waterloo teams reached out to include many communities that had previously been under-represented in the heritage sector. The refinement of historic site documentation helped to build a broad-based culture of conservation.

Over three years HRC staff worked with 25 municipalities in Southern Ontario. As many as seven people at a time worked on the project gaining extremely valuable experience and helping to build a community of professional heritage practice and a culture of conservation. That was the prime goal of the HPI.

Other universities participated to a lesser extent: Queens and Carleton completed about 100 sites each but Waterloo wrote over 800 SOSs. Many Waterloo graduates are now working as heritage planners in both the public and private sector mainly in Ontario.

Then, about 2011, the whole effort came to a grinding halt. There was no more funding for fieldwork or operations. Keeping a register of designated properties reverted to the Ontario Heritage Trust but they only know what municipalities send them. Their system is not compatible with the Canadian Register, which is available but does not appear to have any recent entries. No one any more even dreams of ever seeing funds for actual restoration projects. The idea of creating a culture of conservation is moribund.

This is why, when I see the current Ontario bureaucrats tampering with the wording of regulations and haphazardly adding so-called principles of heritage, I figuratively weep.