Remembrance Day: Uncovering my grandfather’s story of war

The long night in a lifeboat on the Atlantic Ocean

The long night in a lifeboat on the Atlantic Ocean

By Geoff Keelan (MA ’10, PhD ’15) Waterloo MagazineGeoff Keelan is an archivist at Library and Archives Canada.

On April 21, 1941, the SS Nerissa pulled out of the port of Halifax to begin a journey across the Atlantic Ocean to England where Canadian soldiers were preparing for the invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe.

On April 21, 1941, the SS Nerissa pulled out of the port of Halifax to begin a journey across the Atlantic Ocean to England where Canadian soldiers were preparing for the invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe.

On board was a 21-year-old RCMP officer, my grandfather Gerry Keelan.

Nine days and 4,000 kilometers later, my grandfather and some of his fellow officers were finishing a game of bridge around midnight when a terrific blast threw them out of their chairs.

Thankfully, my grandfather’s cabin was the last one on the stern which meant he and his cabin mates were able to jump in a nearby lifeboat.

From this lifeboat, they spotted a Nazi submarine just 15 meters away. Then a second and third torpedo passed under their lifeboat, hitting the Nerissa at the same time — tearing the ship in two and sinking it within seconds.

For the next nine hours, it rained as my grandfather and the other conscious survivors baled water from their leaking lifeboat. Constantly battered by the high waves of the Atlantic Ocean, it was 8 a.m. when a destroyer finally pulled up alongside them just off the coast of Ireland.

Twelve were still alive in the boat when they were finally pulled out of the rocking seas. Seven others had died in the night.

Only 84 of the 290 passengers and crew of the SS Nerissa survived in the single largest loss of Canadian troops en route to England during the Second World War — 62 Canadian servicemen died that night.

My grandfather survived and arrived in England safe and uninjured, where he was stationed at Aldershot, Hampshire with the 21st Army Group as a member of the Military Police. Soon after, he met Irene Trott, an English schoolteacher and my grandmother.

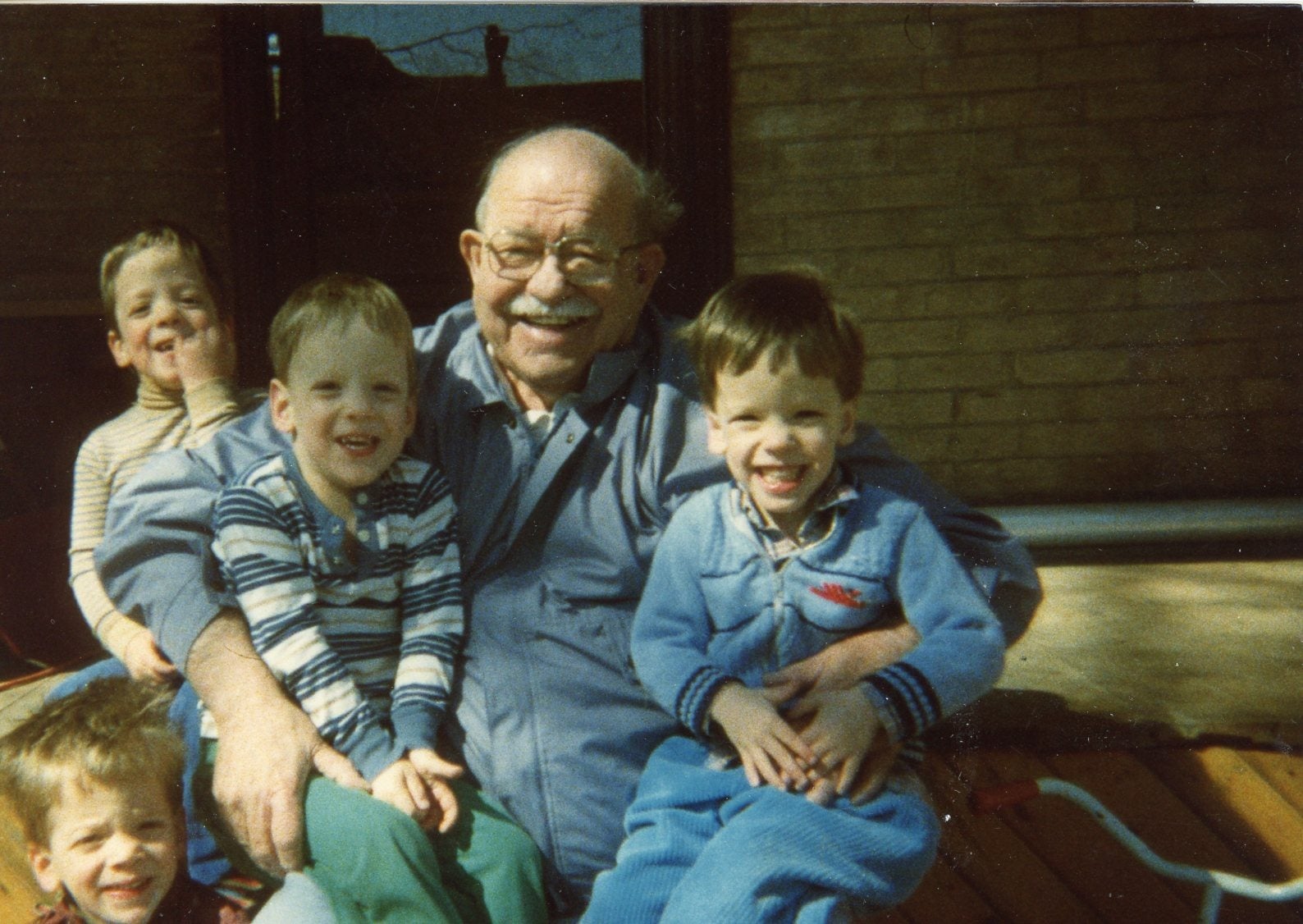

I never heard any of these stories from my grandfather, or even from my father. Grandpa Gerry did not talk much to any of his children or grandchildren about the war before his death in 1998. Or, I was just too young to listen.

Eventually, I studied Canadian history at the University of Waterloo with History Professor Whitney Lackenbauer, beginning my doctoral studies 70 years after the Nerissa sunk.

Although my work did not focus on the Second World War, my experience with Library and Archives Canada eventually helped me get a job there as an Access Archivist. With closer and easier access, I finally took the time to dive deeper into the holdings. I searched, not for my grandfather’s service records, but for records around the ship he had been on.

Although my work did not focus on the Second World War, my experience with Library and Archives Canada eventually helped me get a job there as an Access Archivist. With closer and easier access, I finally took the time to dive deeper into the holdings. I searched, not for my grandfather’s service records, but for records around the ship he had been on.

I discovered that he was interviewed for the Court of Inquiry regarding the sinking, but even still his words cover less than a page. One of the Provost Corps soldiers who roomed with him wrote a much more complete record of the event, which is how I now know of this harrowing night and his brush with death.

On Remembrance Day, when we are meant to remember those who were lost and those who survived, I always consider myself lucky to have even a small part of my grandfather’s story. If I had taken a different career path, my family likely never would have thought to look for anything other than a service file, or known where to look for it.

I reflect on this story whenever I give public or classroom lectures about the war, or when I have a chance to speak with a veteran. For many of us, our family histories are intertwined with wartime struggles, good and bad, but few ever get the chance to see written transcripts of something their grandparents endured.

Most can only imagine their stories in our larger history of the wars, imagining what triumphs and failures they endured and the dark times through which they lived.

There is one reason, above all else, to find and tell these stories: They are meant to be remembered.

All of these stories have the same common thread, whether they be found deep in the archives or told over a glass of wine late at night decades later. There is one reason, above all else, to find and tell these stories: They are meant to be remembered.

Read more

Since the beginning, Waterloo’s co-operative education program has been launching successful careers

Read more

Disney Lam honours her father’s legacy by encouraging the next generation of female software engineers

Read more

Meet the alumni shaking up major league baseball with a pitching robot that replicates pro players

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.