How co-op education helps students innovate for the real world

University of Waterloo teaching award winner tells his engineering co-op students that the best design problems are found, not made

University of Waterloo teaching award winner tells his engineering co-op students that the best design problems are found, not made

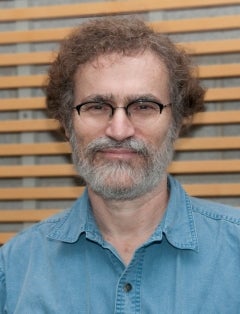

By Heather Bean University Relations Mark Pritzker has some advice for his chemical engineering students in their third term co-op: keep your eyes open for a real problem in your workplace that you can take home when term’s done.

Mark Pritzker has some advice for his chemical engineering students in their third term co-op: keep your eyes open for a real problem in your workplace that you can take home when term’s done.

That problem, he says, is your best bet at a great fourth-year design project or even a future business.

“When I have a bunch of students come to me looking for a project, my first suggestion is try to get a project from a company,” says Pritzker, a professor in Waterloo’s Department of Chemical Engineering. Inventing a problem, he says, can take as much time as solving one—and imaginary constraints might not work out in a realistic way. “The richness comes from the details: the economic factors, the circumstantial constraints—that’s hard to think up, just sitting there.”

In some of the best fourth-year design projects, students’ work is very similar to what a consultant would do. Recently, a group under Pritzker’s supervision designed and costed out a wastewater treatment plant for a major multinational food company.

Dealing with a real-world problem requires a different approach from textbook questions. And Pritzker, a recipient of this year’s University of Waterloo Distinguished Teaching Award, says he and his colleagues try to prepare students for that reality by introducing concrete problems in the very first year of their degree.

Sometimes that prep just means working out numerical problems on blackboards. “It’s more fun to teach with an example,” says Pritzker, And working through problems creates a space for thought and engagement.

“There’s a back and forth when you’re working on a blackboard or whiteboard that has a natural rhythm or pace. There’s a danger with PowerPoint that you’ll move too fast. And there’s something about writing it down that helps reinforce it.” Pritzker also includes concrete problems in take-home assignments and exams.

“In the program in general, we’re putting more emphasis on open-ended problems, where there isn’t one answer,” Pritzker says. “There are different answers depending how you define the problem. In a realistic system, you have to first spend time defining the problem, defining what you’re going to do.”

Preview image credit: iStock/Geber86

Read more

Waterloo co-op student applies engineering and tech skills at Caivan to support purpose-built housing and build land-development expertise

Read more

How Doug Kavanagh’s software engineering degree laid the foundation for a thriving career in patient care

Read more

Redefining capstone learning by bringing students, faculty and community partners together to tackle real-world challenges

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.