Cars that drive themselves

University of Waterloo project explores new world of the driverless commute

University of Waterloo project explores new world of the driverless commute

By Christian Aagaard Communications and Public Affairs

Sometimes it takes a small car to clear a path for the bigger ones.

That's why Steven Waslander and a team at the University of Waterloo are building one-fifth-scale models to advance research into autonomous cars - cars that drive themselves.

"We're taking a jump ahead, beyond one autonomous vehicle driving with a bunch of drivers, to the stage where you have multiple autonomous vehicles all interacting together," Waslander says.

"We're taking a jump ahead, beyond one autonomous vehicle driving with a bunch of drivers, to the stage where you have multiple autonomous vehicles all interacting together," Waslander says.

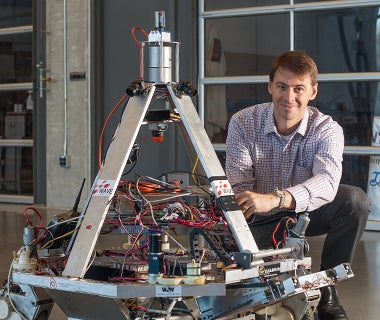

An assistant professor in the department of mechanical and mechatronics engineering, Waslander heads the Waterloo Autonomous Vehicles Laboratory (WAVELab). Besides self-driving automobiles, the lab works on pilotless flying machines and robot rovers.

Whether autonomous cars ever reach a highway isn't a matter of debate any more. Some high-end automobiles have semi-autonomous features, and both Google and Tesla are developing vehicles that leave little of the decision-making to prone-to-distraction drivers.

Autonomous cars could be here in 2020

By 2020, autonomous cars may be parking themselves at dealerships.

The challenge for Waslander, his fellow researchers and the models they build is to extend that independence and raise its trustworthiness. Driverless concept cars today can pace themselves relative to other vehicles; but they have limited ability to deal with the unexpected, such as a ball bouncing into the street.

A truly autonomous car, says Waslander, will be able to venture off familiar routes and understand what’s happening around it at all times. When it spots trouble ahead, it will competently choose a manoeuvre without shaking the occupants inside from their email daze.

The project began in February, backed by federal research funding and Nuvation, a hardware and software design services firm with an office in Waterloo. Faculty and graduate students built one model this summer and have five more to go.

Each will be just under a metre long and loaded with instruments familiar to other WAVELab projects -- sensors for motion and orientation, and cameras to sort out fixed and moving objects. Work on algorithms gets under way this winter.

So who's eagerly driving research into driverless travel? Consumers, Waslander says.

"People are excited about this idea of being able to give up control of the car and not have to pay attention to their driving," he says. "They can think of a hundred different ways of using that time."

Read more

3D printing technology is perfect fit with new Waterloo Institute for Sustainable Aeronautics

Read more

Waterloo team creates vision of a transformed world for architecture biennale

Read more

Waterloo lab helps fill industry demand for additive manufacturing skills

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.