David R. Cheriton School of Computer Science 50th Anniversary

Innovation and Entrepreneurship

The idea was never to be entrepreneurs.

The idea was to innovate and to solve problems.

But if there was a practical application to a solution, and if that application could make some money for the problem solvers, that was just fine.

That’s been the impetus behind many a spinoff company to emerge from the University of Waterloo, and particularly from the David R. Cheriton School of Computer Science.

And it was arguably the driving force behind establishing Waterloo – the City as well as the University – as a prominent tech hub, a distinction that has resulted in the establishment of the David Johnston Research + Technology Park on the institution’s north campus.

The 120-acre park was planned as a partnership between the University, government and business, which exemplifies the co-operative spirit that had led to UWaterloo’s initial entrepreneurial efforts in the first place.

“It was built at a point where there was so much tech activity going on, you could see that it made sense to have a research park; there would be a whole lot of activity that could very naturally fill it out,” said David Taylor, a Professor Emeritus and a former Director of the Cheriton School of Computer Science.

“The School has been willing to latch onto things. Famously, the (School) thinks it’s quite appropriate to interact with industry, whereas, particularly, years ago, that wasn’t necessarily considered the right thing to do in some places.”

This attitude goes back to the earliest days of the University. In fact, the very creation of the University of Waterloo stemmed from a desire to collaborate with industry, which was also the beginning of what is now the world’s largest co-operative education program.

Professor Ralph Stanton, the first Chair of the new University’s Department of Mathematics in the Faculty of Arts, carved the attitude in stone when he hired Wes Graham away from IBM in 1959. Graham brought an industrious bent with him to Waterloo, and he would play a leading role in the future commercialization of ideas generated by himself and the people who worked with and for him.

But, again, it all started merely with a desire to solve a problem.

In 1965, Graham and lecturer Peter Shantz led a team of four undergraduate students – Gus German, Jim Mitchell, Richard Shirley and Bob Zarnke – who wrote a Fortran compiler called WATFOR that allowed users to quickly isolate and correct programming errors. The goal had simply been to make programming faster and easier for students, and it was a spectacular success. Jobs that had taken an hour could now be done in less than a minute.

Other compilers followed, starting with a newer version of WATFOR for the IBM 360/75, and soon the developers were flooded with requests to make their work available to other institutions. An informal Computer Systems Group in charge of the project gave away copies of the work. Then it began to charge a fee, to cover distribution costs – distribution being done on tape reels and sent by postal mail in those pre-Internet days – and to pay for maintenance of the compilers.

Cost didn’t matter. The requests kept coming – from educational, business and government users in at least 40 countries around the world. The money kept coming in too. The CSG, completely unintentionally, had created a market for the software that it was building merely to solve its own problems. Commercialization of work being done in computer science was now a very real option.

“It started us thinking about it,” said Don Cowan, a Distinguished Professor Emeritus in the Cheriton School of Computer Science. He added that another impetus came from the University’s decision in the early 1970s to ensure that intellectual property rights would always belong to creators. Officially, this is known as Intellectual Property (IP) Rights Policy #73.

Policy 73 allows creators to control their intellectual property and do with it as they see fit without having to pay anything or give any rights to the University. It was unheard of at the time for an institution to take such a step, and it’s still rare today.

“It was definitely not mainstream, and it set Waterloo apart from many universities,” said Frank Tompa, also a Distinguished Professor Emeritus. “The Waterloo policy definitely drove the innovation that was here, converting the intellectual innovation into commercial innovation.”

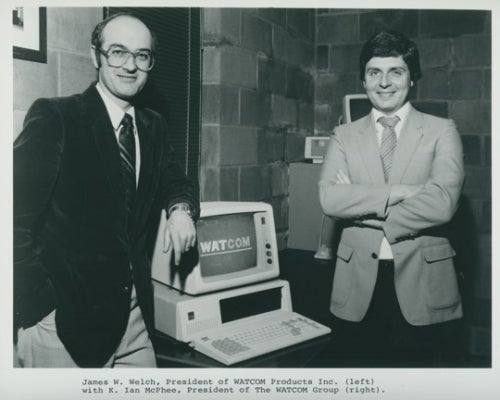

The new policy resulted in the formalization of the Computer Systems Group’s structure, allowing it to work within the University as an independent software marketer and distributor. Eventually, in 1979, this enterprise would officially become UWaterloo’s first spinoff company – Waterloo Basic Enterprises, later known as WATCOM, or Watcom. A precedent had been established.

But even then, it took a while for the reality of the policy to sink in for everyone. Cowan remembers an incident in the early 1980s, when Digital Equipment Corporation arranged to donate $25 million worth of computer hardware to UWaterloo. The trucks were actually on the way to Waterloo when one of Cowan’s colleagues noticed something amiss.

And when Wes Graham found out, his response was quick, decisive, and bold.

“Peter Sprung was reading the contract, and in the contract it said that any software developed on these machines belongs to Digital Equipment,” Cowan said. “And Wes picked up the phone and said, ‘Stop the trucks. We don’t want these computers under these conditions.’ Digital Equipment gave in.”

As the years have passed and further innovations have led to entrepreneurial opportunities for others, one thing remains the same – it all comes from a desire to solve an interesting problem. Which, incidentally, is a common reason why people go into computer science to begin with.

“Programming is a little bit like puzzle solving, and I always liked doing puzzles,” said Tompa, who came to Waterloo to teach after completing his PhD at the University of Toronto in 1974.

“I liked writing a program and having an imaginary user use my program, and it was up to me to satisfy that client,” he said. “That was interesting. Having an imaginary user who relied on me to be able to accomplish what they wanted to accomplish was something that attracted me. And it’s really what has attracted me all along. My research has always been motivated by real users. That’s always been the draw for me.”

He has always believed that if he can turn a specific problem into a general problem, the solution will be applicable on a wide basis.

“You still worry about the specifics of this instance of the problem, so you’re not solving a problem that nobody cares about at the end. And striking that balance is an interesting one for me,” said Tompa, who found such an instance in the mid and late 1980s when he and fellow professor Gaston Gonnet were tasked with a research project to digitize the Oxford English Dictionary (OED).

“Asking questions for the OED answers questions for the World Wide Web,” he said. “The major piece of software that came out of that was a search engine that was probably the basis for forming OpenText Corporation. It was developed into a web search engine, but it wasn’t the first web search engine. It was just a better one, in some senses, for some things at that time, and it, again, helped spur the directions of many things.”

Tompa modestly characterizes this search engine as “a precursor to the kinds of things that you can now do on the Web.

“There were many independent strands starting at that time. We were one of those strands, and everybody was trying to solve problems,” he said. “Because of the OED project, we pushed in a certain direction.

“Our project manager was Tim Bray, and he went off and became very influential in the XML (Extensible Markup Language) development area, and he used a lot of the experience that we had had here on that development. So at the very least there is a direct trace, specifically, back to our project, and I think therefore the project did influence many things.”

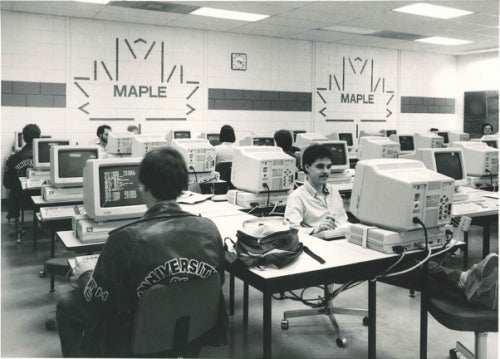

Tompa’s colleague on the OED venture was Gaston Gonnet, who was simultaneously part of a Waterloo Computer Science team that created and commercialized a computer algebra language called Maple. Also on the team were Professor Keith Geddes and one of Geddes’ graduate students, Stephen Watt, who is now Waterloo’s Dean of the Faculty of Mathematics.

“I was fortunate enough to be involved in this as a principal,” said Watt, who completed his PhD under Geddes’ supervision in 1986, and subsequently became a co-founder of Maplesoft. “I had my own graduate research funding from NSERC, and so I was never an employee or a research assistant.

"I participated in the research group, one of the gang, and it was a great experience.”

Many other Waterloo Computer Science students have become entrepreneurs, sometimes with work they’ve begun at school. The University's Velocity startup program offers opportunities for students to get their ideas off the ground through training, coaching and pitching.

Others spend time working in industry before moving ahead with projects they’ve developed on their own. They include Computer Science graduates Danny Zhang and Peter Szulczewski, whose online shopping platform Wish was recently cited as a “unicorn” startup, meaning it’s worth more than $1 billion. Zhang and Szulczewski now fund annual scholarships for Mathematics and Engineering students at Waterloo.

David R. Cheriton, a 1978 PhD graduate and billionaire businessman and philanthropist, is another prominent example. His name now graces the School of Computer Science in recognition of a $25-million investment he made in 2005.

And then there’s Mike Lazaridis, an Engineering and Computer Science student who left UWaterloo only months before his scheduled 1984 graduation and went on to become the billionaire founder of Research In Motion, later Blackberry. He has since invested at least $200 million in the University alone, through private funding for the Institute for Quantum Computing, and a donation to create the Mike & Ophelia Lazaridis Quantum-Nano Centre.

These success stories have been generous to UWaterloo because they recognize the encouragement they received while they were students here. Cowan and Watt, entrepreneurs themselves, said it’s a reflection of the relationship between the University and its people who are actively involved in research and creation.

By contrast, Watt said, some other universities will allow their creators to have some IP rights, but will claim up to 75 per cent of the net benefits of what they create.

“Well, would you rather have 75 per cent of nothing, or would you rather have the occasional success story come and give you a building? That’s what we’ve got,” he said.

“It’s an incredible benefit,” added Cowan, who is a co-founder of Watcom and other UWaterloo spinoffs. “The big benefit to the University is, no, they don’t own any IP, but I’ll bet you they’ve gotten more money from people saying ‘Thank you’ than they would have if they had tried to exploit stuff.”

Despite their entrepreneurial successes, these innovators in computer science are still adamant that it’s the research and the quest for solutions to problems that motivates them.

“I entered computer science before it was invented, and software engineering before it was invented. I’ve always been very practical and pragmatic,” Cowan said. “As I tell people, I believe God put computers on this Earth to be used. Many people, computer scientists, study them purely as an object of curiosity, if you will. I tend to actually try to apply them to lots of problems.”

The other primary motivator is the feeling of genuine support that they receive from the Cheriton School of Computer Science and from the University as they pursue their interests.

“It’s not so much the creator ownership that makes the biggest difference. It makes a little difference,” Tompa said. “What makes the biggest difference is the environment and the encouragement – the fact that, at Waterloo, you are encouraged to take your ideas in any direction that makes sense.

“The University really supports the area that you are interested in pursuing. That’s a strength of Waterloo.”

And that support extends to research ideas that may not have readily apparent commercial applications. If it’s important to a computer scientist for any reason, Tompa said, they can find backing for it.

“A problem need not be a commercially attractive problem to still be an interesting problem to work on, and one that is worth solving,” he said.

“You pick projects because they are interesting and potentially useful, and then you start worrying about how can you support it.”

That’s reassuring to researchers like Dan Vogel, who brings a fascinating art background to his work. Along with his undergraduate and graduate degrees in Computer Science, he also has a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Intermedia from the Emily Carr University of Art + Design in Vancouver, BC.

He came to UWaterloo on a postdoctoral fellowship in 2011 and is now an assistant professor in the Human-Computer Interaction Lab at the Cheriton School of Computer Science. His focus is on building better computer experiences for people – making them more user-friendly, more expressive, and more accessible.

“It’s trying to find and explore other ways for us to interact with computers. Some of them might not be the best ways, or may not be globally optimum ways, but they might have advantages for certain groups, or certain kinds of tasks,” he said. “But, unlike in a corporation that’s going to go after the largest market, we’re not bound by those constraints.

“You have to take some risks. Being transformative, to me, is about taking risks – reasonable, calculated risks to try to get to some transformative outcome.”

Bringing an art sensibility to research work at the Cheriton School of Computer Science is unique, and Vogel was surprised at how easily that approach was accepted and welcomed.

“The fact that I brought this art side, and that it didn’t seem to faze anyone, and it seemed to actually be seen as a good thing, I thought that was pretty incredible, because I was somewhat apprehensive about that being seen as not a pure computer science,” he said.

“The main thing that you learn at art school is how to be creative, or how to solve problems creatively. And it turns out that the skills that you learn at art school are really excellent skills for research. You’re learning how to discover things, try things, how to quickly prototype things, and that’s what you do whether you’re doing print-making or you’re doing human-computer interaction research.”

Vogel and his colleagues envision a type of augmented reality – a “far future image” – where every surface can be a digitally addressable display. And such a development may be closer than it might initially seem.

“It’s a little far reaching, but I don’t think it is, considering what we’ve seen in the past decade. Technology’s a pretty amazing thing, what one can do,” he said.

If a commercial application for this work does emerge, it’s entirely possible that Vogel could one day be a principal in a firm that joins the ranks of other spinoffs like Watcom (now Sybase), Maplesoft and OpenText, all of which still have bases in Waterloo.

Sybase and OpenText are located in the David Johnston Research + Technology Park; Sybase is on Wes Graham Way, and OpenText, fittingly, is on Frank Tompa Drive.

Frank Tompa is understandably proud to have been honoured in such a way. He is equally proud to represent the work that went into making the honour possible.

“There is definitely a spirit here at Waterloo that encourages entrepreneurship. Other schools try to imitate that in some way, or try to foster it – they have courses in entrepreneurship, they have little startup labs and things like that,” he said. “But the course here is in the ether, rather than being in a classroom.

“Whether it is part of the students that we attract in the beginning, or it’s something that we pick up from the others after they’re here, I don’t know.”

“We’ve worked very hard with a lot of students to try to help them become entrepreneurs, not necessarily to our benefit, but somebody has had an idea and we would encourage them in any reasonable way that we could,” Cowan said.

“If there’s research that has a practical use, let’s get it out there.”