Did You Know?

Did You Know? was a series run by the Office of Indigenous Relations for the duration of Indigenous History Month in 2021. These educational facts were uploaded weekly featuring information on various topics pertaining to Indigenous histories in Canada.

We invite you to explore these educational posts and share widely.

Did You Know?

The Haldimand Treaty of 1784

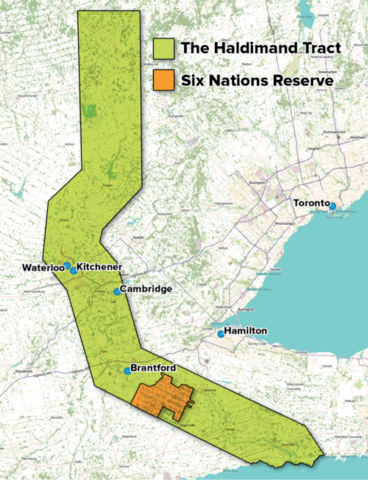

Map source: Adam Lewis, “Living on Stolen Land,” Alternatives Journal December 2015

The Haldimand Treaty of 1784

The Haldimand Treaty is an agreement that granted a tract of land to the Haudenosaunee (Six Nations or Iroquois Confederacy), in compensation for their alliance with British forces during the American Revolution. The University of Waterloo campuses are located on the Haldimand Tract, which extends 10km on either side of the Grand River.

Throughout the late 1700s and 1800s, the Crown and Haudenosaunee disputed rights to the land title. Negotiations about the title to the Haldimand Tract still continue between the Canadian government and the Six Nations Confederacy.

Treaty Rights and Responsibilities

Treaty Rights and Responsibilities

Treaties are not only for Indigenous Peoples.

Canadians have treaty rights and responsibilities too but often don’t think of them. In Ontario, there are more than 40 treaties and agreements covering the whole province. Most Canadians actually live in a treaty area and where they don’t, they are living on unceded Indigenous lands (never ceded or legally signed away their lands to the Crown or to Canada).

Indian Hospitals in Canada: 1920s - 1980s

Indian Hospitals in Canada: 1920s - 1980s

Content Warning: This post contains details of violence and death, past and present, of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples.

The history of Indian hospitals in Canada is not as well-known as that of residential schools but is as horrific in both its actions and the implication of those actions.

Health care for Indigenous people, such as it was, was motivated by a number of factors that range from keeping as many patients 'interned' as possible to maintain government funding, to ensure a steady number of subjects for medical and nutritional experiments, and ensure that the European population was protected from exposure to 'Indian tuberculosis'.

Segregated medical treatment for Indigenous patients was also the norm in community hospitals where they were treated in the basement or 'Indian annexes'. This aspect of Canadian history shows that healthcare for Indigenous Peoples was never a priority and never on par with the care available for Europeans. Unfair treatment, discrimination, and racism towards Indigenous Peoples continues to exist in the Canadian healthcare system. When Joyce Echaquan, a 37-year-old Atikamekw woman, began experiencing stomach pains, she checked herself into a hospital in Joliette, Quebec. Echaquan livestreamed herself in her hospital bed screaming and calling for help. But instead of receiving the help she needed, Echaquan faced incredibly racist and insensitive taunts by Quebec health care staff. Joyce Echaquan passed away on September 28, 2020, shortly after the video was posted. Echaquan could have been saved if she'd been more closely monitored, an expert witness told the coroner's inquiry in Trois-Rivières, Quebec. (CBC News, 27 May 2021)

Joyce's Principle(PDF), a document created by the council of Atikamekw Nation and the Atikamekw Council of Manawan, aims to guarantee that Indigenous people have equitable access to health and social services without discrimination.

The Métis National Council

The Métis National Council

Prior to Canada’s crystallization as a nation, a new Indigenous people emerged out of the relations of First Nations people and European settlers.

While the initial children of these unions were individuals who simply possessed mixed ancestry, subsequent intermarriages between those of mixed ancestry resulted in the creation of a new Indigenous people with a distinct identity, culture, and consciousness – The Métis Nation.

For generations, the Métis Nation has struggled for recognition and justice in Canada. In 1982, the existing Aboriginal and Treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples in Canada were recognized and affirmed in Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. This was a turning point for the Métis Nation, with the explicit recognition of the Métis as one of the three distinct Aboriginal peoples.

Before the Métis National Council (MNC) was formed, Métis had been involved in pan-Indigenous lobby groups and organizations. This did not allow the Métis Nation to effectively represent itself. As a result, the MNC was formed in March 1983.

Métis National Council President Clément Chartier at Parliament introducing Bill C-92, 2019. Credit: Métis National Council

The Métis National Council General Assembly adopted the following “National Definition” in 2002:

“Métis” means a person who self-identifies as Métis, is distinct from other Indigenous peoples, is of historic Métis Nation Ancestry and who is accepted by the Métis Nation.

Since 1983, the MNC has represented the Métis Nation nationally and internationally.

Residential Schools in Canada: 1920s - 1990s

Residential Schools in Canada: 1920s - 1990s

Content warning: This post contains details of violence and death, past and present, of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples.

Education was used as a tool of oppression for Indigenous Peoples through “Indian Residential Schools”, an extensive school system set up by the Federal government. They were administered by churches from the early 1920s to the mid-1990s. The Roman Catholic Church operated three-fifths of the schools, the Anglican Church one-quarter, and the United and Presbyterian Churches the remainder.

The goal of residential schools was, according to the Indian Act, “To kill the Indian in the child” and was based on the premise that Aboriginal cultures were inferior to White Christian ones. Children were forcibly removed from their homes and parents at a young age. At these schools, they were forbidden to speak their first language, their hair was cut, and they were stripped of their traditional clothes and given new uniforms. In many cases, the school staff gave children new names or used numbers to refer to them.

A group of female students and a nun pose in a classroom at Cross Lake Indian Residential School in Cross Lake, Manitoba, February 1940. Credit: Reuters

Physical, sexual, and emotional abuse were disturbingly common at the schools. A large percentage of students also did not receive enough food to eat. Poor living conditions and malnutrition meant that many became sick with preventable diseases such as tuberculosis and influenza.

While the government began to close the schools in the 1970s, the last school remained in operation until 1996 - The Gordon Residential School in Punnichy, Saskatchewan.

Many Canadians were shocked to learn that the remains of 215 children had been discovered at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia. However, this tragic discovery did not come as a surprise to Indigenous Peoples, as thousands of Indigenous children never returned home from residential schools and their whereabouts remain unknown.

Many individuals living in what is now known as Canada have little knowledge of residential schools, or issues such as persistent unclean drinking water in Indigenous communities. Many people are also unaware that the abuse that Indigenous children suffered at residential schools left them with deep scars that last for generations and still have not been healed. Sadly, the residential school system was only one among many systems of violence and harm against Indigenous Peoples. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) concluded that more than 4,100 children died while attending a residential school, however this figure is a conservative estimate. In 2015, the TRC outlined 94 Calls to Action. As of December 2019, a study by the Yellowhead Institute reported only nine of the 94 calls to action are complete.

The Inuit Taipiriit Kanatami

The Inuit Taipiriit Kanatami

Inuit are an Indigenous People living primarily in Inuit Nunangat, the Inuit homeland. The majority of their population reside in 51 communities spread across Inuit Nunangat and they have lived in their homeland since time immemorial. Inuit communities are also among the most culturally resilient in North America with around 60% of Inuit reporting an ability to converse in Inuktut (the Inuit language).

Inuit Nunangat is comprised of four Inuit regions in Canada. The term "Inuit Nunangat" is a Canadian Inuit term that includes land, water, and ice. Inuit regard their homeland's land, water, and ice to be essential to their culture and way of life. Inuit Nunangat is a vast region which includes the Inuvialuit Settlement Regions (Northwest Territories), Nunavut, Nunavik (Northern Québec), and Nunatsiavut (Northern Labrador).

The reason to form a national Inuit organization evolved from shared concern among Inuit leaders about the status of land and resource ownership in Inuit Nunangat. Industrial encroachment into Inuit Nunangat from projects such as the then proposed Mackenzie Valley pipeline in the Northwest Territories and the James Bay Project in Northern Québec, prompted community leaders to take action.

Map of the Nunavut and Nunavik regions. Credit: Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada

The Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), formerly known as the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada ("Inuit will be united"), was founded in February 1971 by seven Inuit community leaders at a meeting in Toronto. The ITK now serves as the national voice protecting and advancing the rights and interests of all Inuit in Canada. In 2001, ITC changed its name to Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, which means "Inuit are united in Canada." This name change reflects the settlement of land claims agreements in all Inuit regions following the Labrador Inuit Association's signing of an Agreement-in-Principal for the Labrador land claims agreement.

The Truth about Taxes

The Truth about Taxes

Most Indigenous People pay Canadian taxes. Although federal tax exemptions for Indigenous People have existed at least since the consolidation of the Indian Act in 1876, they only apply in very specific and limited conditions.

Under sections 87 and 90 of the Indian Act, Status Indians are exempt from paying federal and provincial taxes on their personal and real property that is on a reserve. Since income is considered personal property, Status Indians who work on a reserve do not pay federal or provincial taxes on their employment income. However, income earned by Status Indians offreserve is taxable.

Métis and Inuit, on the other hand, do not qualify for this exemption.

Disclaimer: The Canada Revenue Agency recognizes that many Indigenous People in Canada prefer not to describe as Indians. The term Indian is used in this context solely because it has legal meaning in the Indian Act.

Please note that this post was not written by tax experts. If you have any specific questions about Indian taxation, please contact the Canada Revenue Agency or a qualified accountant who is familiar with Indian taxation.

Jordan's Principle

Jordan's Principle

Jordan River Anderson, from Norway House Cree Nation, was born in 1999 with a rare muscle disorder known as Carey-Fineman-Ziter syndrome and stayed in the hospital from birth. When he was two years old, doctors said he could move to a special home for his medical needs. However, the Canadian federal and Manitoban provincial governments could not agree on who should pay for his home-based care.

As the federal and provincial governments argued, Jordan stayed in the hospital until he passed away at the age of five.

Every child deserves access to services such as health care and supports at school; however, First Nations children often face many challenges accessing the same services as other children in Canada. This is because different levels of government fund different services for First Nations children, especially those living on-reserve.

Jordan River Anderson, The Messenger (film by Alanis Obomsawin) Credit: Toronto International Film Festival Inc.

In 2007, in response to public criticism and recommendations from Indigenous groups, Canada's Parliament passed a motion in support of "Jordan's Principle," a policy meant to ensure that First Nations children have equitable access to government-funded health, social, and educational services. Although practice took an exhausting 10 years to live up to the aspiration of the principle, we've finally reached a time when justice is possible.

Today, Jordan's Principle is a legal obligation. This means it has no end date. While programs and initiatives to support it may only exist for short periods of time, Jordan's Principle will always be there and will support First Nations children for generations to come.

This is the legacy of Jordan River Anderson.

Between July 2016 and March 31, 2021, more than 911,000 products, services and supports were approved under Jordan's Principle. (Government of Canada, 2021)

"When we step back from Jordan's Principle and really think about it, what we're really talking about is ending racial discrimination against little kids," says Cindy Blackstock, Executive Director of the First Nations Child & Family Caring Society of Canada.

No child should be left behind because of their race. We owe it to the kids, and we owe it to the ancestors

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) reports comment extensively on child welfare, referencing it as a continuation of Indian residential schools, in which the removal of Indigenous children from their families and communities continues through a different system.

With this continued crisis resulting in children losing their languages, cultures and ties to their communities, the TRC cited changes to child welfare as its top Calls to Action.

These Calls to Action include:

- Reducing the overrepresentation of Indigenous children in the care of child welfare;

- Publishing data on the exact numbers of Indigenous children in child welfare and the reasons for apprehension and costs associated with these services;

- Fully implementing Jordan's Principle;

- Ensuring that legislation allows for Indigenous communities to be in control of their own child welfare services; and

- Developing culturally appropriate parenting programs (TRC, 2015).

It is important to acknowledge and consider the legacy of the Indian residential school system when looking at Indigenous child welfare in Canada in order to contextualize the roots of the child welfare crisis and ongoing removal of First Nations, Inuit and Métis children from their homes and communities.

The Assembly of First Nations

The Assembly of First Nations

First Nations is a term used to describe Indigenous Peoples in Canada who are not Métis or Inuit. They are the original inhabitants of the land that is now known as Canada, and were the first to encounter sustained European contact, settlement and trade. There are 634 First Nations in Canada, representing more than 50 Nations and 50 distinct Indigenous languages.

First Nations culture is rooted in storytelling. Since time immemorial, First Nations have passed on knowledge from generation to generation through their Oral Traditions to teach their beliefs, history, values, practices, customs, rituals, relationships, and ways of life.

First Nations culture and teachings of their ancestors are preserved and carried on through the words of Elders, leaders, community members and young ones. These teachings form an integral part of First Nations identity as nations, communities, clans, families, and individuals.

The Assembly of First Nations (AFN) was founded in April 1982 as a result of movements to restore Chiefs as the voice of First Nations in a Canada-wide deliberative assembly.

In the late 1970s, First Nations increasingly pushed for the rights of self-government. Furthermore, by the late 1970s, First Nations communities needed direct representation in order to respond to the federal government's constitutional proposals, including the proposed patriation of the Canadian Constitution.

First Nation leaders (Chiefs) from across Canada direct the work of AFN through resolutions passed at Chiefs Assemblies held at least twice a year. AFN's National Executive is comprised of the National Chief, 10 Regional Chiefs and the chairs of the Elders, Women's and Youth councils.

As directed by Chiefs-in-Assembly, the responsibility of the National Chief and the AFN is to advocate on behalf of First Nations.

This involves launching and coordinating national and regional conversations, lobbying initiatives and campaigns, legal and policy analysis, and communication with governments, which includes promoting the development of relationships between First Nations and the Crown.

Malnutrition Studies on Indigenous Populations in Canada

Malnutrition Studies on Indigenous Populations in Canada

Content warning: This post contains descriptions of abuse experienced by Indigenous adults and children.

During the 1940s and 1950s, Canadian government scientists used malnourished Indigenous populations as unwitting subjects in experiments to test nutritional interventions.

The work began in 1942, when government scientists visited several Indigenous communities in northern Manitoba and discovered widespread hunger and malnutrition. Their immediate response was to investigate the issue by testing nutritional supplements. From a group of 300 malnourished individuals selected for the study, 125 were given vitamin supplements. The rest served as 'untreated' controls.

In 1947, similar experiments emerged after government inspectors found widespread malnutrition in residential schools. Over a period of five years, the researchers used almost 1,000 children at six schools for their experiments.

At one residential school, where it was discovered that students were receiving less than 50% of the daily recommended intake of milk, the researchers tested the effects of tripling the children's milk allowance. However, this testing only occurred after the children's milk intake was kept at the same, low level for two additional years in order to provide a baseline against which the effects could be compared. At another school, the researchers conducted a randomized, double-blind controlled trial. One group of students were given vitamin C supplements and the other received a placebo.

Credit: F. Royal/National Film Board of Canada/Library and Archives Canada

Again, this testing only occurred after a two-year baseline period.

Children at a third school were given bread prepared with fortified flour that was not approved for sale in Canada. As a result, many of them developed anaemia.

The researchers also denied the children at all six schools from receiving preventative dental care. This was done because oral health was a parameter used to assess nutrition. These experiments were not only unethical, but also bad science. They didn't appear to try and prove or disprove any hypothesis or make any statistical correlations.

Although the school experiments were presented at conferences and published, they led to no important advances in nutritional science or improvements in conditions at the schools. "They mostly just confirmed what they already knew," says Ian Mosby, who studies the history of food and nutrition at the University of Guelph.