Writing My Mother

Five years before Kathleen Venema (PhD '99) arrived at the University of Waterloo, she moved to Ndejje, a small town in south-central Uganda.

Five years before Kathleen Venema (PhD '99) arrived at the University of Waterloo, she moved to Ndejje, a small town in south-central Uganda.

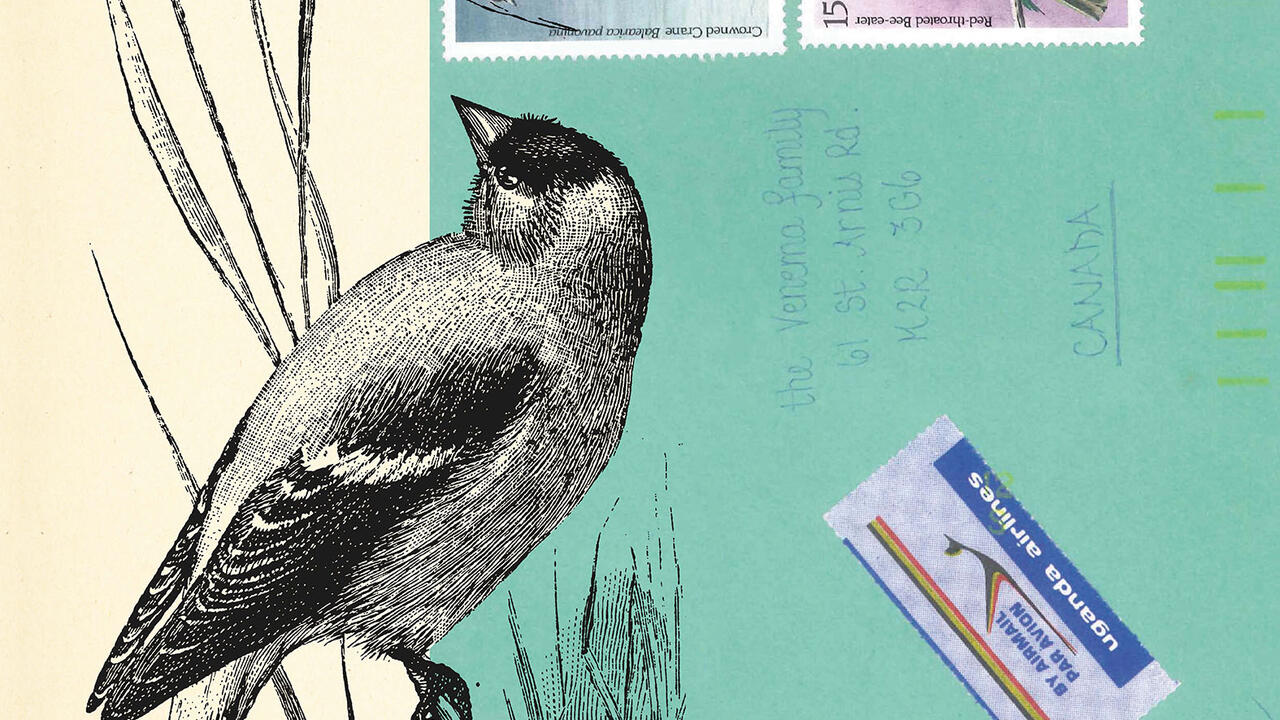

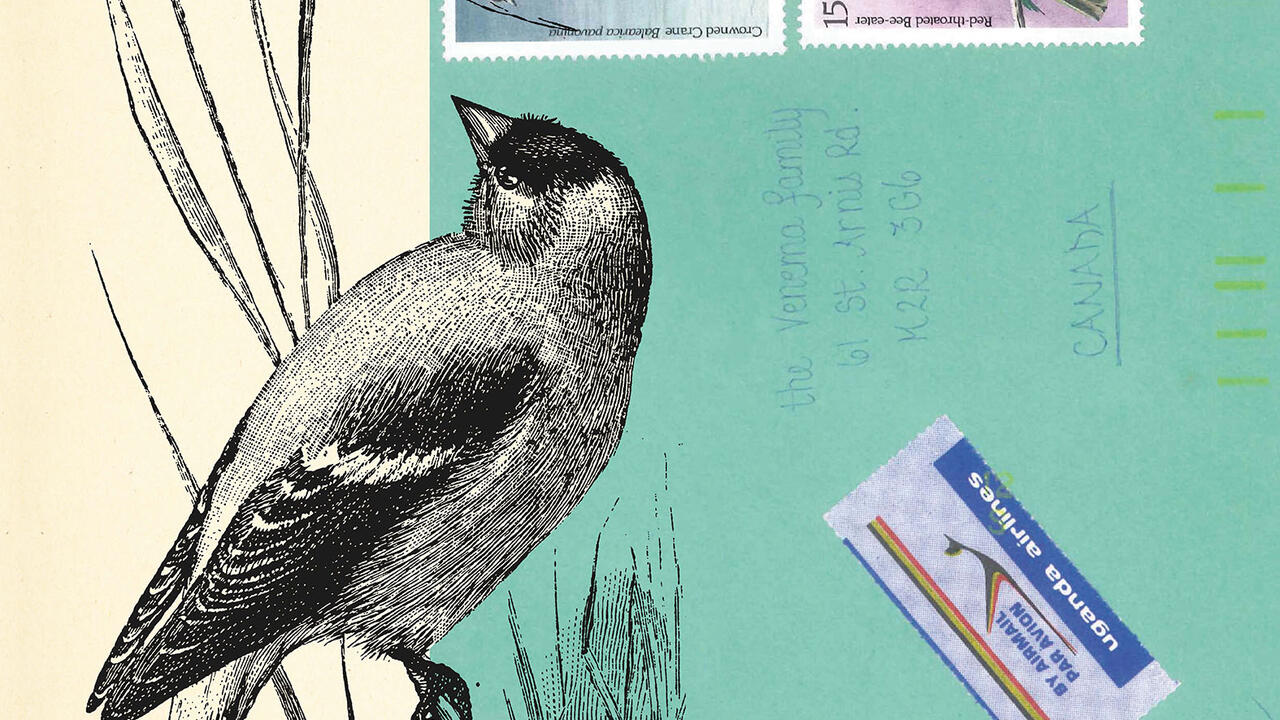

By Kathleen Venema (PhD '99) AlumnusI was 25 years old, had taught junior high school in northern Manitoba for the previous three years, and was now a volunteer with the Mennonite Central Committee. My official assignment was to teach science and mathematics to young adults at a nationally acclaimed teacher-training college that had been devastated in the recently-ended civil war. The realities of post-war life meant that I had a lot of learning to do, and so I wrote almost constantly, sending hundreds of letters to friends and family in Canada as a way to process my unfamiliar new life. It was August 1986, the not-so-distant past, but email was seven years in the future and unimaginable. My correspondents and I hand-wrote our letters, slid our carefully addressed envelopes into mailboxes, and waited patiently (and often impatiently and sometimes futilely) for responses that took weeks and sometimes months to arrive. Of my many correspondents, no one wrote more frequently than my mother, and our two-hundred-plus letters make up a quarter of the little archive I’ve created, of letters I sent and letters I received throughout that extraordinary time.

The literal distance between my mother and me during my years in Uganda brought us even closer, and she was as thrilled as I was when I determined that grad school would be my next adventure. I’d decided on UWaterloo’s MA, a program that came highly recommended by one of my undergraduate professors, who’d recognized and encouraged my recurring interest in language and rhetoric. I began my studies in the fall of 1991 imagining a career as a professional writer, ideally with NGOs involved in international development, but quickly rediscovered how much I loved studying and learning. The decision to continue to a PhD program – specifically Waterloo’s new PhD in Language and Literature, with its blend of literary, rhetorical, and discourse studies – was a logical next step.

The literal distance between my mother and me during my years in Uganda brought us even closer, and she was as thrilled as I was when I determined that grad school would be my next adventure. I’d decided on UWaterloo’s MA, a program that came highly recommended by one of my undergraduate professors, who’d recognized and encouraged my recurring interest in language and rhetoric. I began my studies in the fall of 1991 imagining a career as a professional writer, ideally with NGOs involved in international development, but quickly rediscovered how much I loved studying and learning. The decision to continue to a PhD program – specifically Waterloo’s new PhD in Language and Literature, with its blend of literary, rhetorical, and discourse studies – was a logical next step.

Bearing out the program’s ability to place its graduates in high quality academic and research positions, I’ve been a member of the English Department at the University of Winnipeg since shortly after graduating. When my beloved Mom was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2005, I designed a project that had us spending the next five years of Friday afternoons engaged in activities we’d loved doing together all our lives: talking (especially re-telling family stories), walking, singing, writing, and reading, including reading the hundreds of letters we’d sent to and from Uganda thirty years earlier. My book about our time together – Bird-Bent Grass: A Memoir, in Pieces (Wilfrid Laurier University Press 2018) – interweaves three main stories: one about my immigrant mother’s life as I’ve been able to piece it together; one about the adventures and challenges of my years at Ndejje, told through letter-excerpts; and one about the profound connection my mother and I nurtured and treasured, even in the midst of Alzheimer’s erosions. From start to finish, Bird-Bent Grass evinces critical, analytical, and creative skills and deft rhetorical shaping that honours what I learned throughout my studies at the University of Waterloo.

Bearing out the program’s ability to place its graduates in high quality academic and research positions, I’ve been a member of the English Department at the University of Winnipeg since shortly after graduating. When my beloved Mom was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2005, I designed a project that had us spending the next five years of Friday afternoons engaged in activities we’d loved doing together all our lives: talking (especially re-telling family stories), walking, singing, writing, and reading, including reading the hundreds of letters we’d sent to and from Uganda thirty years earlier. My book about our time together – Bird-Bent Grass: A Memoir, in Pieces (Wilfrid Laurier University Press 2018) – interweaves three main stories: one about my immigrant mother’s life as I’ve been able to piece it together; one about the adventures and challenges of my years at Ndejje, told through letter-excerpts; and one about the profound connection my mother and I nurtured and treasured, even in the midst of Alzheimer’s erosions. From start to finish, Bird-Bent Grass evinces critical, analytical, and creative skills and deft rhetorical shaping that honours what I learned throughout my studies at the University of Waterloo.

Read more

A Waterloo couple reflects on the campus that shaped their careers, their values, and their love story

Read more

To meet our AI ambitions, we’ll need to lean upon Canada’s unique strengths

Read more

From optometry and pharmacy to public health and therapeutics, Waterloo alumni are powering Canada’s health care sector

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.