The impacts of war

Waterloo professor dedicates years of research to civilians and children displaced following WWII.

Waterloo professor dedicates years of research to civilians and children displaced following WWII.

By Wendy Philpott Faculty of Arts

Lynne Taylor, professor of history.

“What war does to the men and women who go to the front to fight is very important to recognize and remember,” says Lynne Taylor, professor of history. “But war is also about the impact on civilians. I think it is important we remember that too.”

This month, with Remembrance Day and Holocaust Education Week, we have an opportunity to learn more about our past and present, and to honour the many people whose lives were taken or indelibly changed by war.

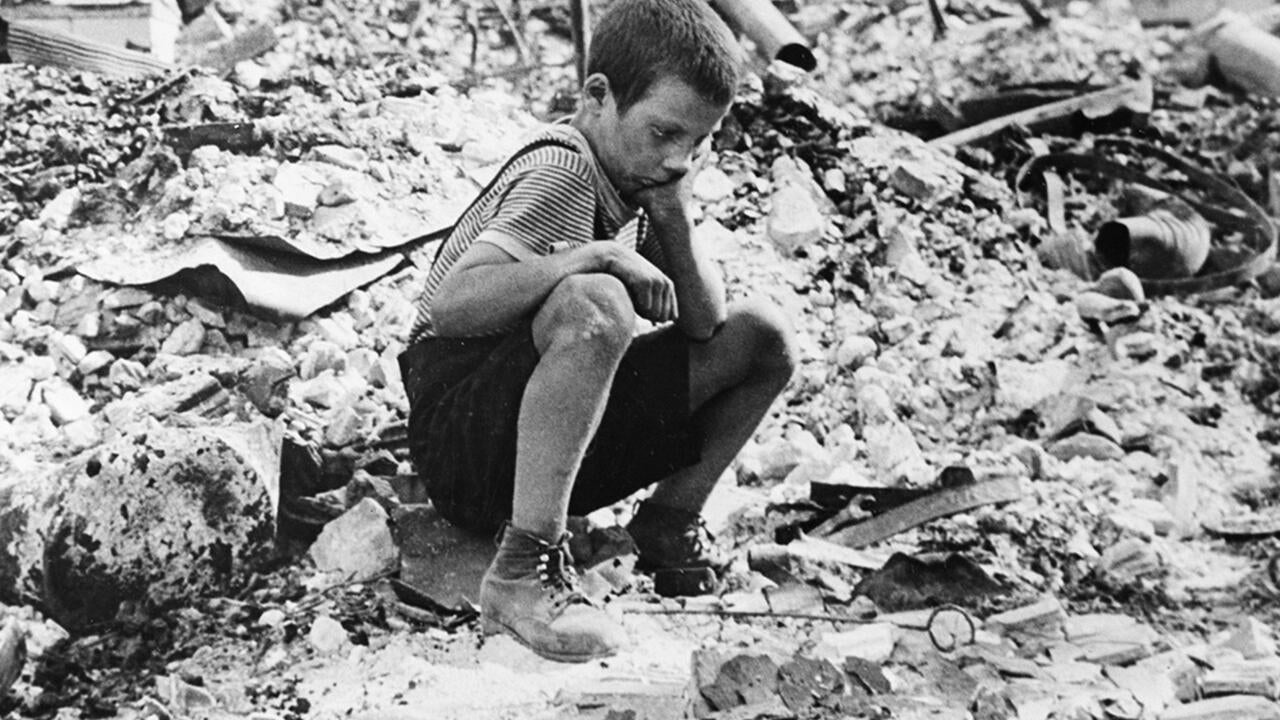

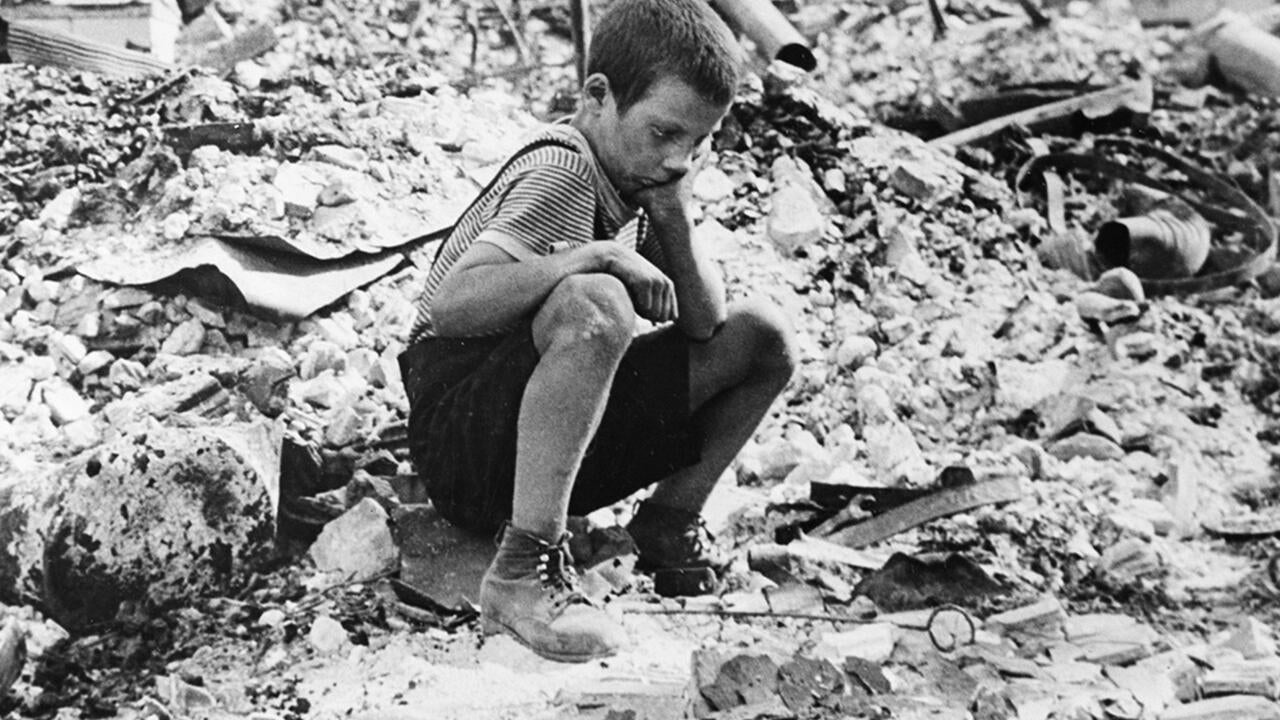

Among the stories of civilians directly impacted by war are the displaced children in Europe immediately following WWII— a topic Taylor has researched for more than decade. Orphaned or separated from their parents in concentration camps, labour camps or military attacks, children—from babies to teenagers—were gathered into the displaced persons camps in the postwar American occupation zone in Germany.

“These children had no legal guardians at the end of the war, and, in many cases, they were effectively stateless because nobody knew their nationality,” says Taylor.

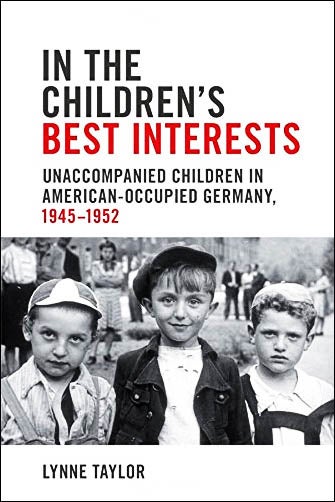

In her latest book, In the Children’s Best Interests, Taylor examines the challenges faced by the U.S. occupation authorities and international agencies responsible for caring for and resettling the approximately 40,000 unaccompanied children.

In her latest book, In the Children’s Best Interests, Taylor examines the challenges faced by the U.S. occupation authorities and international agencies responsible for caring for and resettling the approximately 40,000 unaccompanied children.

“It turns out to be a really complicated story that hinges around the problem of trying to determine the children’s nationalities,” she says, “because that governs who can speak for them as unaccompanied minors, and ultimately where and how they would be settled.”

In most cases, these children had no documentation, and an infant or young child could not speak for themselves.

“So, when you don’t even know what country a child is from, who speaks for these children and makes decisions for them?”

Much of Taylor’s book explores and untangles the complexities and conflicts between the American military occupation authorities, the various national governments and agencies responsible for the care and ultimate resettlement of these children.

From displaced persons camps in occupied Germany, children were sent to various countries including Canada.

“We took in a large number of displaced persons, over 157,000 between 1945 and 1951,”says Taylor. “Relative to our population, Canada was one of the more generous countries when it came to taking in these children.”

In 1952, the last of the children were settled—that is, reunited with relatives, repatriated, resettled or absorbed into German society. For some, the process took seven years, which means they effectively grew up in the camps. Many of these children were never reunited with their families.

With three books out on the subject, Taylor is often contacted by people who were displaced children or by their relatives who want to understand more about their family history. One woman recently emailed about her search to track down an aunt, her mother’s twin, who was separated when they were brought to the United States for adoption. Taylor does her best to respond to the inquiries by pointing to a specific archive or agency that may have information, and to help the families understand the world in which their relatives grew up.

“The records of these displaced and resettled children are both voluminous and almost impossible to work with,” says Taylor, whose own research journey has included numerous visits to five major archives on two continents.

Beyond the documents, she has been able to interview former displaced children – now in their 70s and 80s, and some speaking about their story for the first time.

“It’s very powerful because you’re working with people’s memories. They put a lot of trust in you, that you will respect their memories. And they feel that is important that their story get told and recorded, before it is lost."

In all of her conversations with unaccompanied children who settled in Canada and elsewhere, says Taylor, “the thing that strikes me is how resilient the children were in the face of it all. They were all scarred by it, but the resiliency and the determination to soldier on is really impressive."

“The human spirit is very hard to break. That’s one of the positives I take from this story.”

Banner photo: Polish boy in ruins of Warsaw 1939. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Read more

Personal diaries of nurses and doctors reveal the toll war takes on those who care for the dying and injured, says Waterloo researcher

Read more

Many soldiers were 22-years-old when they died—the same age students are when they graduate from university

Read more

“The three Canadian war cemeteries in the Netherlands remain immaculate after 70 years. They stand as enduring reminders of the relationship between our two countries,” says Waterloo researcher

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.