From greenhouse gas to green energy

University of Waterloo scientists capture carbon and turn it into sustainable, clean fuel

University of Waterloo scientists capture carbon and turn it into sustainable, clean fuel

By Media RelationsScientists at the University of Waterloo have achieved a historic breakthrough in transforming the carbon dioxide emissions driving climate change into clean fuels.

The process, which has been refined over a two-year period, could play a significant role to help decarbonize industrial emissions and boost both the environment and national economies.

“This technology will help countries achieve the Paris Agreement’s net-zero carbon emissions goal by 2050. Nobody has achieved such high production of these hydrocarbon by-products before this,” said project leader Dr. Yimin Wu, a professor of mechanical and mechatronics engineering at Waterloo. “This new process will give more economic benefits to companies and industries, making carbon capture more economically feasible to adopt.”

This process was a result of the National Research Council (NRC) Canada’s Materials For Clean Fuels Challenge program, a multi-year program aimed at developing new technologies to decarbonize Canada’s energy sectors. Wu’s team collaborated with the NRC, which provided a $160,000 grant.

The Waterloo engineers had three goals: to mitigate carbon dioxide emissions — typically from industrial and transportation sources — that cause climate change, to make decarbonization financially feasible and to incorporate renewable electricity to develop new materials for zero-emission transportation fuels and chemical feedstocks for industry.

While other researchers have tried to do the same thing, they often failed to convert the carbon dioxide efficiently enough to make their processes economically viable. Wu’s team has overcome this stumbling block with their process which utilizes a different catalyst than prior attempts at a similar outcome.

“We achieved 94 per cent of faradaic efficiency of carbon conversion to multi-carbon products,” said Wu. “Faradaic efficiency” measures the amount of electricity used to produce by-products in an electrochemical process. The system also has the ability to convert low concentrations of carbon dioxide in amounts typically seen from industrial flues or motorized vehicles.

“This gives a promising sign that this technology can be adopted at point-sources for carbon dioxide conversion,” Wu said.

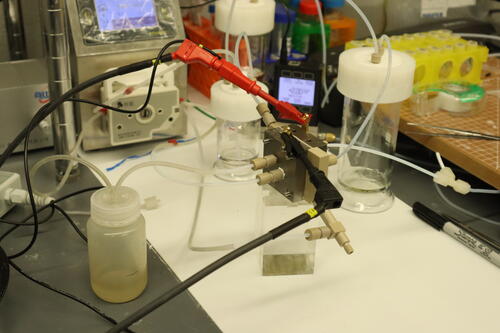

Wu and his colleagues synthesized a copper-silver, single-atom alloy catalyst in a laboratory to produce an ink-like substance. They sprayed that substance on an electrode in a flow reactor. Next, they introduced carbon dioxide and water into the reactor from one side and, after applying electricity to the electrode, succeeded in producing hydrocarbon and oxygen by-products from the other side of the reactor.

Wu and his colleagues synthesized a copper-silver, single-atom alloy catalyst in a laboratory to produce an ink-like substance. They sprayed that substance on an electrode in a flow reactor. Next, they introduced carbon dioxide and water into the reactor from one side and, after applying electricity to the electrode, succeeded in producing hydrocarbon and oxygen by-products from the other side of the reactor.

Those by-products include ethanol, which can be used as a clean fuel, and ethylene, which can be used to manufacture plastics. More importantly, these by-products would divert, and thereby reduce, carbon dioxide emissions.

Wu said the materials used in this process — copper, which is an abundant mineral, and silver in a single-atom form —make it extremely cost-effective to implement. In addition, the process uses electricity more efficiently than other carbon-capture processes.

Wu and his colleagues now hope to increase the long-term stability of the system’s reactor to operate with 1,000 hours with no downtime. But with the commercial potential of their research already apparent, Wu and his colleagues plan to create a spin-off company featuring their technology with a U.S. patent pending and early interest from investors.

More information can be found in the research paper, “Cascade electrocatalysis via AgCu single-atom alloy and Ag nanoparticles in CO2 electroreduction toward multi-carbon products,” published earlier this month in Nature Communications.

Read more

Waterloo prof leads a team of researchers to improve water quality through a community-focused approach underpinned by technical excellence

Waterloo researcher Dr. Tizazu Mekonnen stands next to a rheometer, which is used to test the flow properties of hydrogels. (University of Waterloo)

Read more

Plant-based material developed by Waterloo researchers absorbs like commercial plastics used in products like disposable diapers - but breaks down in months, not centuries

Read more

Engineering researchers team up to tackle the plastics pollution problem with microbial innovation and engineering design

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.