Healing eyes with contact lenses

Patented bandage contact lens material could release drugs as needed to help eye abrasions heal faster

Patented bandage contact lens material could release drugs as needed to help eye abrasions heal faster

By Media RelationsA cross-disciplinary University of Waterloo team has developed a new contact lens material that could act as a bandage for corneal wounds while releasing drugs in a controlled manner to help the eye heal faster.

Typically, corneal abrasion patients spend seven to 10 days wearing a clear, oxygen-permeable bandage contact lens, often instilled with eyedrops containing antibiotics. However, the one-time antibiotic application makes it difficult to ensure enough drugs stay on the eye for sustained treatment.

“It’s a targeted-release drug delivery system that is responsive to the body,” said Dr. Lyndon Jones, a professor at Waterloo’s School of Optometry & Vision Science and director of the Centre for Ocular Research & Education (CORE). “The more injured you are, the more drug gets delivered, which is unique and potentially a game changer.”

Jones knew there was a market for a drug-delivering bandage contact lens that could simultaneously treat the eye and allow it to heal. The question was how to develop it.

As the University of Waterloo has several researchers and entrepreneurs building technology to disrupt the boundaries of health, Jones was able to team up with Dr. Susmita Bose (PhD’23), Dr. Chau-Minh Phan (PhD’16) and Dr. Evelyn Yim, an associate professor of chemical engineering working on collagen-based materials. Rounding out the team were Dr. Muhammad Rizwan, a former postdoctoral fellow, and John Waylon Tse (MASc’18), a former graduate student, both with Yim’s lab.

Collagen is a protein naturally found in the eye that’s also often involved in the wound healing process – however, it’s too soft and weak to be a contact lens material. Yim found a way to transform gelatin methacrylate, a collagen derivative, into a biomaterial 10 times stronger.

One unique property of collagen-based materials is that they degrade when exposed to an enzyme called matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), which is naturally found in the eye.

“These enzymes are very special because they’re involved in wound healing, and when you have a wound, they’re released in greater quantity,” Phan said. “If you have a material that can be degraded in the presence of this enzyme, and we add a drug to this material, we can engineer it so it releases the drug in a way that is proportional to the amount of enzymes present at the wound. So, the bigger the wound, the higher the amount of drug released.”

The team used bovine lactoferrin as a model wound-healing drug and entrapped it in the material. In human cell culture study, the researchers achieved complete wound healing within five days using the drug-releasing novel contact lens material.

Another benefit of the material is that it only becomes activated at eye temperatures, providing an inbuilt storage mechanism.

The next step is fine-tuning the material, including entrapping different drugs in it.

The scientists believe their material has great potential – not only for the eye but potentially for other body sites, especially large skin ulcers.

A study outlining the researchers’ work was recently published in the journal Pharmaceutics.

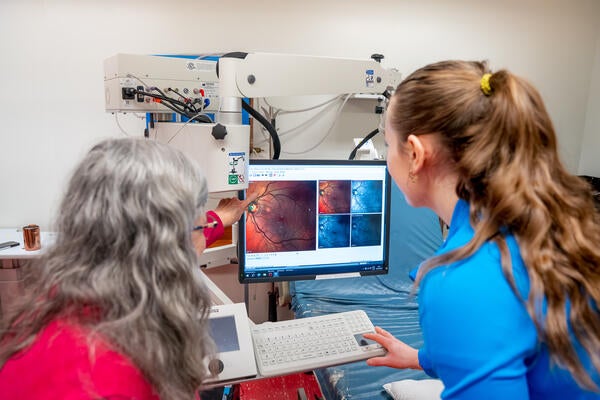

Dr. Melanie Campbell and graduate student Lyndsy Acheson study an image of a retina. They are looking for protein deposits found in association with brain diseases, such as Alzheimer's, FTLD-TDP and ALS (University of Waterloo).

Read more

Researchers show retinal images can accurately differentiate ALS and Alzheimer’s, increasing possibility of earlier diagnosis

Read more

New evidence-based classification rules expand access and improve fairness for Para Cross Country and Para Alpine skiers

Dr. Travis Craddock, professor and Canada Research Chair, says the team's findings change our basic knowledge of biology (University of Waterloo).

Read more

New study reveals quantum-level effects in biology with major implications for treatment of some brain diseases

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.