Q and A with the experts: Vaccine hesitancy among the Black community

Higher vaccine hesitancy persists among Black Canadians when compared to the general public

Higher vaccine hesitancy persists among Black Canadians when compared to the general public

By Media RelationsDespite groups designated as visible minorities being at an increased risk of infection and mortality from COVID-19, higher vaccine hesitancy persists among Black Canadians when compared to the general public.

Some of the reasons put forward by members of the Black community as to why they’re hesitant to be vaccinated are lack of confidence in the safety of the vaccine and concerns about its risks and side effects.

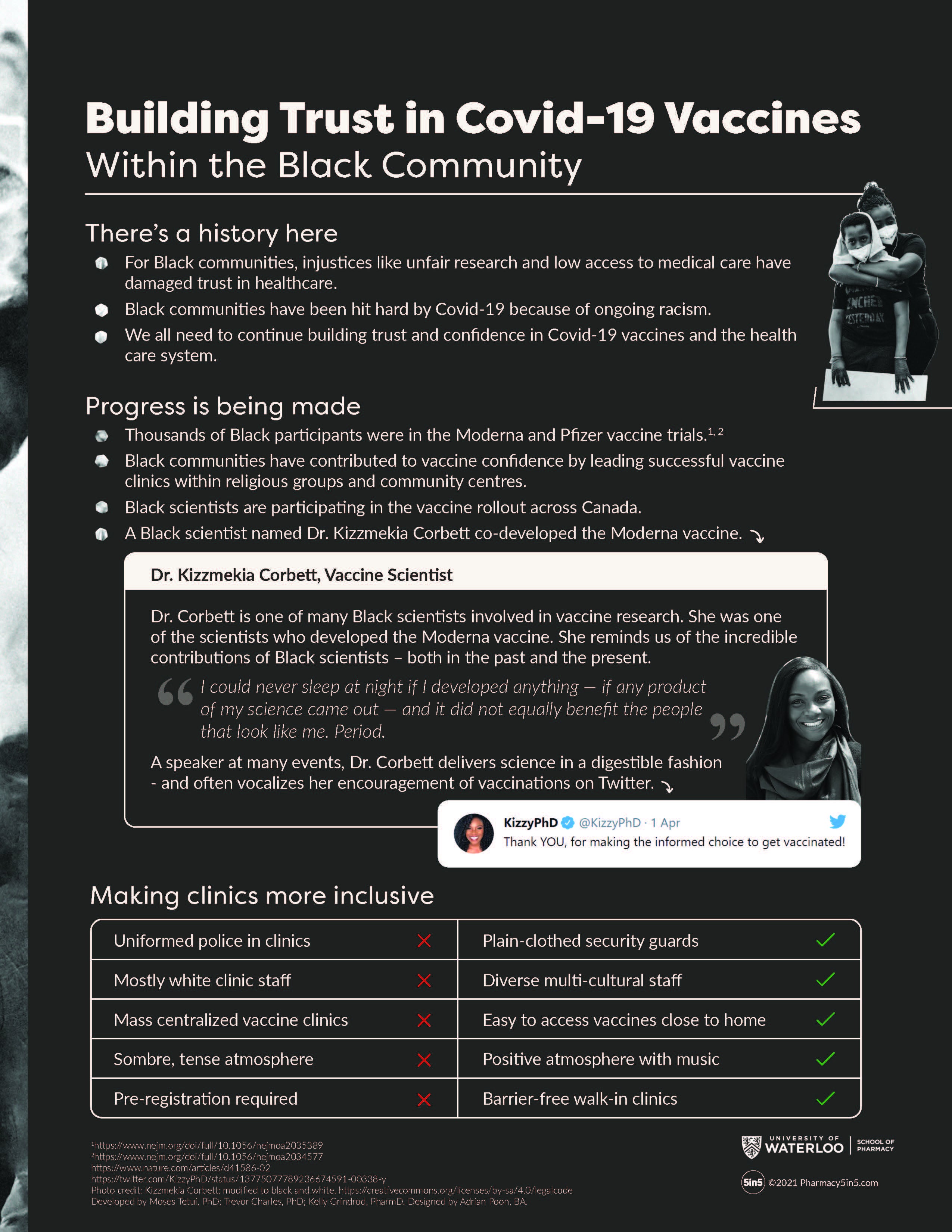

A team of researchers from the University of Waterloo including microbiology professor Trevor Charles, pharmacy professor Kelly Grindrod, and health-systems researcher Moses Tetui, seek to allay some of those fears.

Are the COVID vaccine side effects the same for Black people compared to those who are not Black?

Yes, there is no evidence that the side-effects from COVID-19 vaccines are different for any ethnic or racialized group. For all the vaccines approved in Canada, most people experience a sore arm for a few days after the vaccine. Around half of people experience tiredness and a headache, and less than half have body aches, chills or feel feverish. These are all normal and expected side effects and are common with many other vaccines as well. They are signs that the immune system is learning how to recognize COVID.

For all these vaccines, these side effects will happen within a day or two of getting the vaccine and will disappear by the third or fourth day for most people. While there is a small chance that there will be a serious side effect, these are rare. Rare but serious side effects might be something like an allergic reaction. It’s always a great idea to speak with a health professional about any serious allergies or other health conditions or concerns you may have before you receive any vaccine.

Are vaccines developed with considerations given to how they might affect Black people different from other races?

Yes, around 10 per cent of the Pfizer and Moderna trial populations identified as Black. The studies demonstrated that there were no differences in efficacy or safety in any racialized or ethnic group. It is also important to note that there is no known evidence that would suggest that vaccines affect people differently based on racial differences. In the past, Black and Indigenous communities were used to test vaccines in what has widely been criticized and categorized as unethical today. The Moderna vaccine was co-developed by a Black immunologist named Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett.

Is the wait-and-see approach adopted by some members of the Black community before receiving their first dose putting them at greater risk?

Yes, vaccination is the best protection against severe disease arising from COVID-19 infection. Systemic racism means Black communities are more likely to live in crowded housing conditions or to work in higher-risk environments. When some members of the Black community decide “to wait and see” it can further increase the risk of COVID within the community. Often, people use a “wait and see” approach when they have certain questions or concerns about the vaccines. A better approach would be to discuss those concerns with a trusted health care provider or community leader. It’s important to note that the wait and see approach could have a similar risk for any racial or ethnic group depending on their risk of exposure.

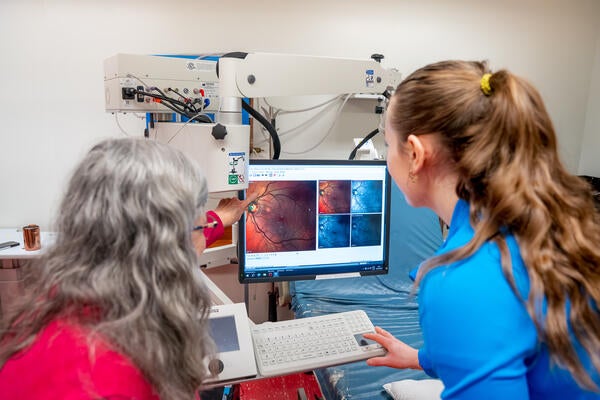

Dr. Melanie Campbell and graduate student Lyndsy Acheson study an image of a retina. They are looking for protein deposits found in association with brain diseases, such as Alzheimer's, FTLD-TDP and ALS (University of Waterloo).

Read more

Researchers show retinal images can accurately differentiate ALS and Alzheimer’s, increasing possibility of earlier diagnosis

Read more

New evidence-based classification rules expand access and improve fairness for Para Cross Country and Para Alpine skiers

Hand holding small pieces of cut colourful plastic bottles, which Waterloo researchers are now able to convert into high-value products using sunlight. (RecycleMan/Getty Images)

Read more

Sunlight-powered process converts plastic waste into a valuable chemical without added emissions

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.