National Indigenous Peoples Day offers a chance for recognition and personal reflection

Knowledge Integration museum exhibit challenges non-indigenous people to confront legacy of Canadian settler colonialism

Knowledge Integration museum exhibit challenges non-indigenous people to confront legacy of Canadian settler colonialism

By Peter Stirling Communications OfficerWalking to the 2019 Knowledge Integration (KI) Exhibition (KIX), I had a feeling it would be one of those days that I love my new job. I was charged with photographing the Mashkawizii exhibit viewing by Chief Ava Hill, of the 56th Elected Council of the Six Nations of the Grand River, and member of the Board of Governors at the University of Waterloo.

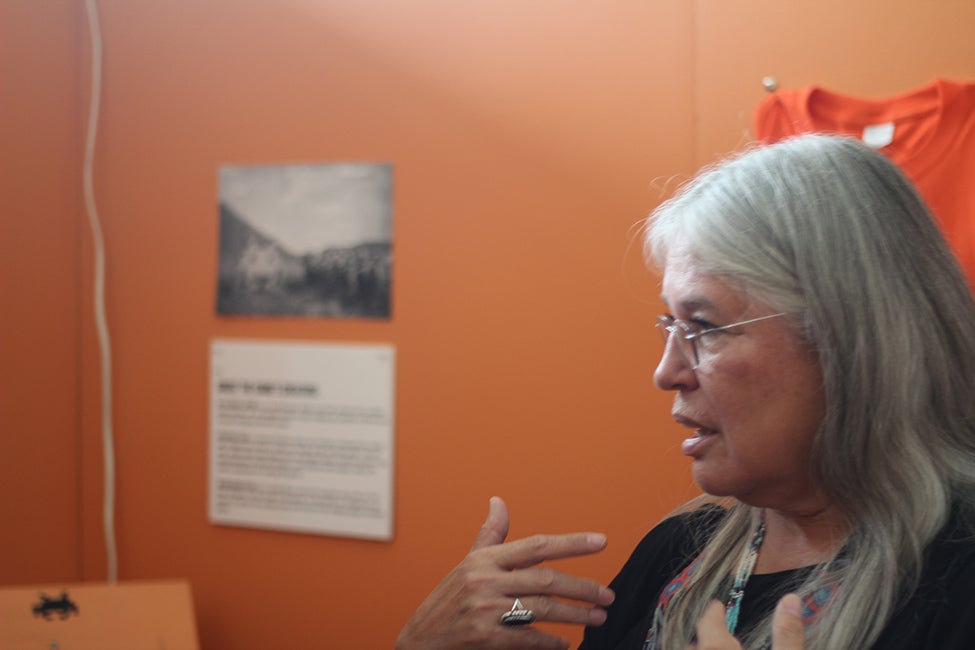

As Hill began her tour, I hovered about taking pictures, but quickly felt out of place as the gravity of the exhibit I was photographing impressed upon me. Putting away my camera, I excused myself. This was not a photo opportunity; it was an occasion for a local elder to connect with each exhibit as a story she already knew personally.

Mashkawizii: Paint it Orange; Resilience in the Face of Trauma, was designed as a shared learning space that aims to change the predominantly negative narrative surrounding Indigenous people, and to demonstrate the resilience displayed by these communities in the face of the intergenerational trauma caused by the Canadian residential school system.

Little girl in a pink dress (Lila Bruyere’s story inspired the image of the little girl found throughout the exhibit). The space is organized to follow the little girl’s journey from the erasing of her culture to taking back her narrative, as Lila and so many other survivors have done.

For First Nations, the colour orange is used to mark the impact that these schools had on their communities. On September 30th, Canadians are encouraged to wear orange as a way to remember a time of year when children were often taken away for the first time to the schools.

After touring the display alone, Chief Hill walked through again with KI students, Ben Ang, Findley Dunn, Ted Haag, Claire Quong, and Stephanie Ye-Mowe, who had created the exhibit. Professor Rob Gorbet, director of Knowledge Integration, explained that the students had been reluctant to take on this project, as they were not themselves members of the Indigenous community they sought to represent. However, after meeting with Waterloo’s Indigenous Student Association, they were encouraged to pursue the exhibit, and they set themselves to the task, with the goal of creating a visual space where Indigenous people could tell their own story.

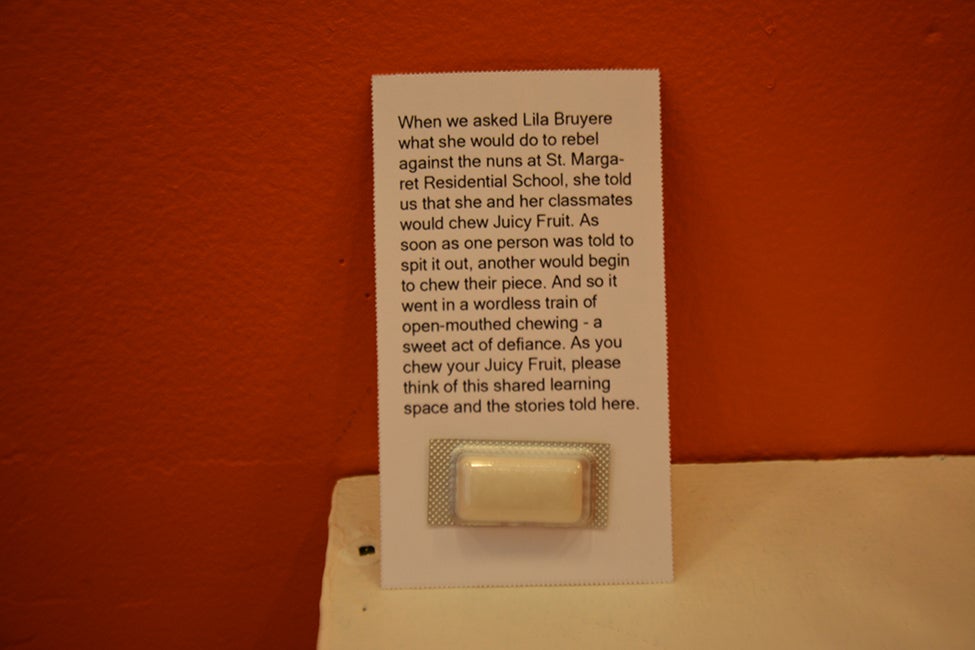

A piece of Juicy Fruit gum that visitors are encouraged to chew as they consider the exhibits. The card reads: When we asked Lila Bruyere about what she would do to rebel against the nuns at St. Margaret Residential School, she told us that she and her classmates would chew Juicy Fruit gum. As soon as one person was told to spit it out, another would begin to chew their piece. And so it went in a train of open-mouthed chewing – a sweet act of defiance. As you chew your Juicy Fruit, please think of this shared learning space and the stories told here.

Chief Hill remarked on how well the students had captured the voices of her people’s past, specifically in relation to the Mohawk Institute Indian Residential School in Brantford, Ontario, which local First Nations children attended.

Hill took time to explain how detrimental the residential school environment was for those who attended.

Chief Ava Hill tours the Mashkawizii exhibit and speaks with the student designers

“The older kids at the school would often show the younger ones how to wrap their arms around exposed heating pipes as a way of feeling that they were getting a hug from their parents, said Hill. “But the lack of love children received also led to difficulty expressing love and emotion; an inhibition that still extends to many in their adult lives today.”

Hill also spoke of how aboriginal youth rally around sports as an outlet and social bonding opportunity, and how she is now actively working with Canada’s government to encourage sports competitions for Indigenous youth.

Having grown up in a protestant missionary-run boarding school myself, I was reminded of how those of us who reconnected in the early days of social media, rallied around our school’s sports team name — the Fanda Eagles — as we sought accountability for the many abuses that took place there.

We had succeeded to some extent in this effort, and cases of abuse and reconciliation in the Protestant Church have gained more widespread media attention in recent years. But as I listened to Hill speak about the extent of abuses faced by First Nation’s communities, I wondered if we had acknowledged their suffering to the same extent as our own.

I had not; a reality that is no doubt due to not having taken the time to personally learn about their story. Certainly, the detrimental ramifications of boarding school abuse and growing up with a lack of empathy and caring does not change across cultural experiences, as the Mashkawizii exhibit clearly outlines. Broken relationships, addictions, and drug abuse are a much too common result, but Hill also had a message of hope for reconciliation.

“If we could just learn more about each other’s cultures, maybe we could move past this history together. There is much for us to listen to and learn from all cultures,” said Hill.

The Mohawk Institute Indian Residential School is currently being refurbished as an Interpretation Centre and funds are being raised through a Save the Evidence campaign, with the goal of a 2020 opening. The Mashkawizii exhibit has been chosen to show at the Woodland Cultural Centre, in Brantford, Ontario, from August 26 to November 21, 2019.

Read more

Here are the people and events behind some of this year’s most compelling Waterloo stories

Read more

Researchers awarded funding to investigate ecology, climate change, repatriation, health and well-being through cultural and historical lens

Read more

Industry partners and talented Waterloo students envisioned a decarbonized future and how they can drive transformative change in the energy sector

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.