Ian MacNaughton’s planning footprint spans Ontario

Waterloo honours the astounding legacy of planning alum with a new scholarship

Waterloo honours the astounding legacy of planning alum with a new scholarship

By Faculty of EnvironmentThe University of Waterloo is remembering Ian MacNaughton (BA ‘68, MA ‘71), a remarkable force in Ontario’s urban planning sector, after his death on Saturday, October 7, 2023.

To honour his rich legacy UWaterloo, which awarded MacNaughton its 50th Anniversary Alumni Award in 2007, is inaugurating an award in his name, the Ian MacNaughton Memorial Award, and aims to name a space in his honour. With this award and space naming, MacNaughton will continue the impact he made in life by inspiring and supporting future environment students.

A lot of people dream of making the world around them a better place. MacNaughton is a rare individual who managed to make that dream happen. In fact, it was from an early age, exactly what he’d planned.

In the four-plus decades after he became one of the first three students to graduate from the University of Waterloo’s nascent school of urban and regional planning, he proved it time and again. Thanks to MacNaughton’s professional and voluntary work, communities across southern Ontario work better, the province’s natural environment is better guarded and economic growth is more sustainable today.

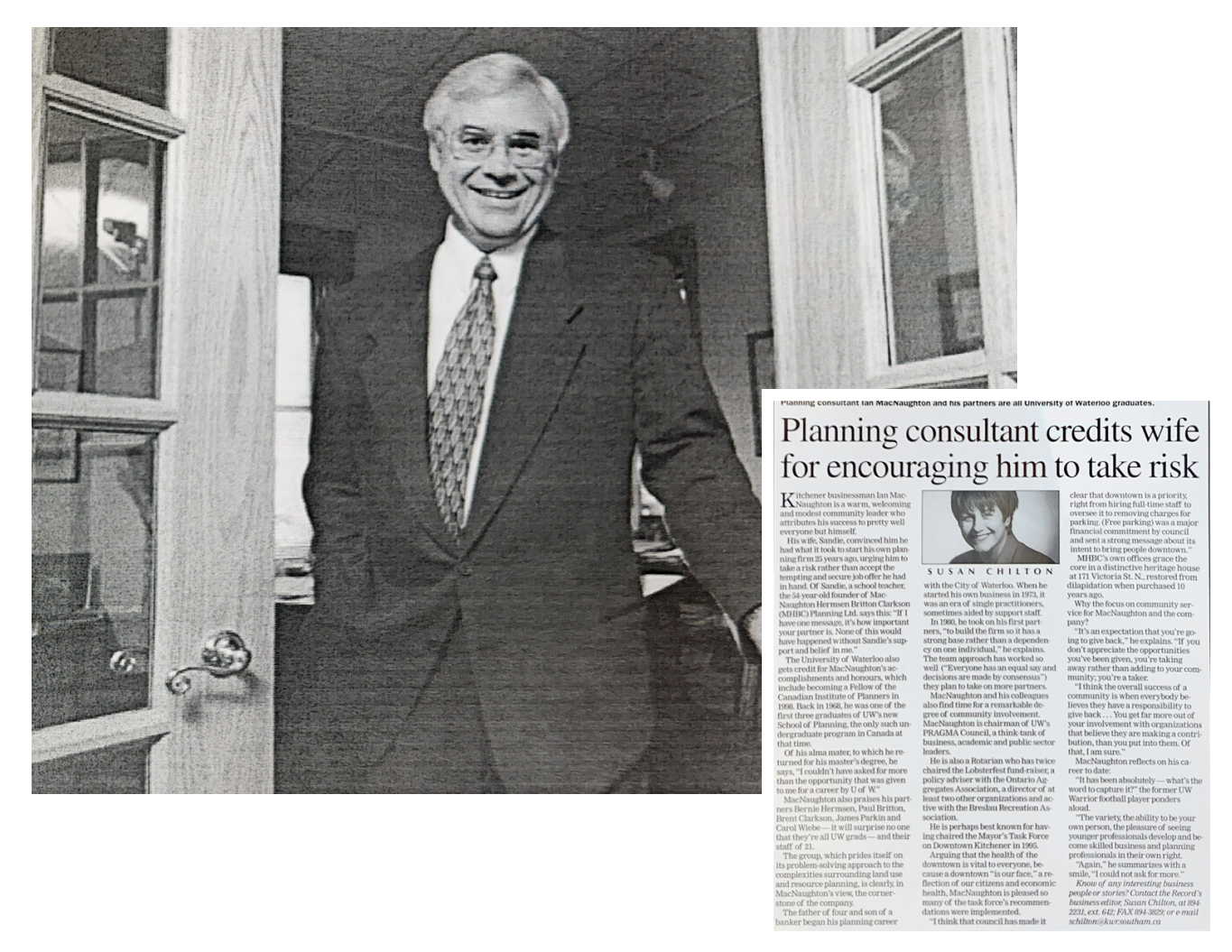

The tiny company he started with a handful of staff was a seed that blossomed into one of Ontario’s most successful private planning firms, MHBC Planning. Today, MHBC employs 130 people in Kitchener, Toronto, Burlington, Barrie and London. MacNaughton and his company helped manage decades of unprecedented growth in Ontario by promoting responsible development that aimed to reconcile economic, environmental and social needs.

“He was a star in our planning community,” said Ken Seiling, Waterloo Region’s regional chair from 1985 to 2018. “During all my years in municipal government, Ian stood out as a forceful yet fair, balanced and ethical planner. He was part of the community and wanted good things for this region, which was evident in many of the things he did.”

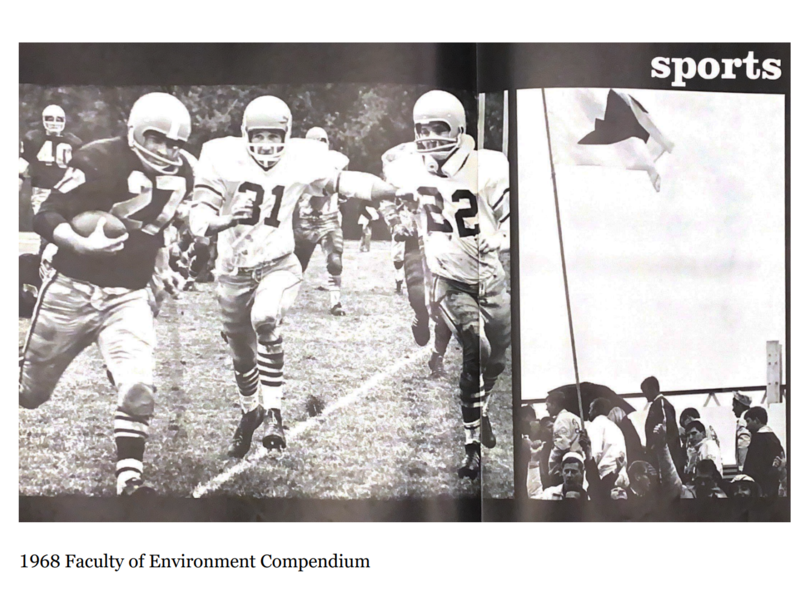

As proud as he is of his life’s work, MacNaughton admitted it couldn’t have happened without his years at Waterloo. He arrived in 1964 on a campus less than a decade old to study geography because he was “lousy at math and sciences.” A self-confessed late-bloomer who flunked grade 13, MacNaughton also chose Waterloo to play football. He also built a silo-building enterprise as a summer job to pay his bills. The lessons in teamwork, drive and perseverance he picked up as a student lasted throughout his impressive career.

“I was the first up the silo and the last down,” he recalled, explaining the work kept him fit for football while honing his leadership skills.

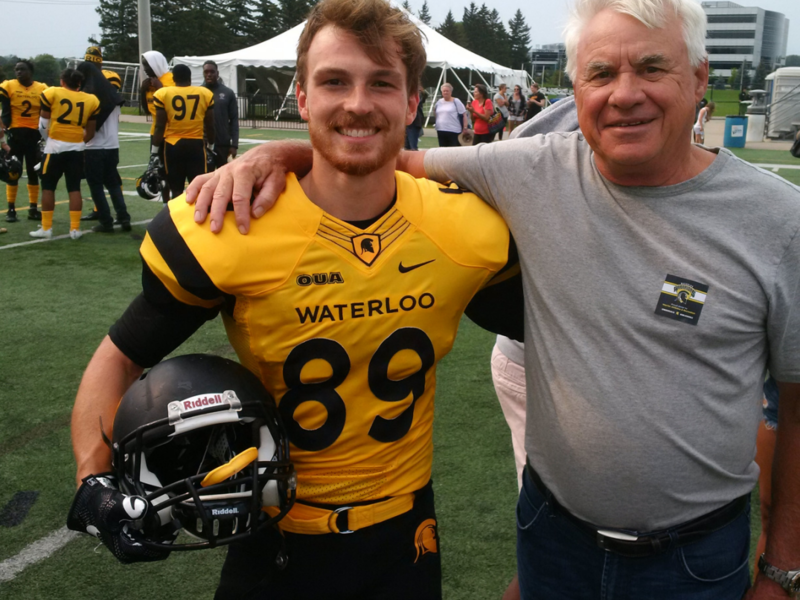

MacNaughton with a football scholarship recipient.

MacNaughton on the field. Photo from the 1968 Faculty of Environment Compendium.

It was the mentorship provided by two extraordinary UWaterloo professors that opened MacNaughton’s eyes to the benefits solid planning could and should provide to society. Bob Dorney, whom he described as “one of the foremost ecologists in North America” and “a giant” in the field, convinced MacNaughton that responsible planning must respect the natural environment. Len Gertler, head of Waterloo’s School of Planning, impressed upon him that balancing diverse and often competing interests was crucial to good planning in the modern era.

“I fell in love with planning,” MacNaughton recalled of his years at UWaterloo. “I ate it up like candy.”

His education continued after he graduated with his Honours Bachelor of Arts, Urban and Regional Planning in 1968 (the School’s first graduating class) and worked as the City of Waterloo’s assistant planner. While that served as an apprenticeship, he craved more formal knowledge and returned to UWaterloo where he completed a Master of Arts, Regional Planning and Resource Development in 1971.

“What I learned was a holistic approach,” he said. “It was like seeing a radar screen that goes across a problem and being able to grasp the whole problem.”

After graduating with his MA, he accepted a job as planner for Oxford County — but never worked a day there. At the urging of his wife, Sandie, he started his own planning consultancy in 1973. It was built on the foundations of his own philosophy: First, see the big picture. Second, establish a hierarchy of interests that includes client needs, community hopes, environmental protection and economic imperatives. Third, in a conflict find the best fit for the long-term public interest.

Space won’t permit a full list of MacNaughton’s accomplishments, here are just a few. He coordinated the progressive overhaul of local government in Oxford County. He helped prepare the Niagara Escarpment Plan which continues to guard one of Ontario’s most revered natural features. In Waterloo Region, he played a central role in establishing Canada’s first municipal Environmental Advisory Committee, which put environmental considerations on every planning table, including those in his own office. Observing the development of local subdivisions, he concluded it was better in every way, even for the bottom line, to design growth with nature in mind, rather than just bulldoze.

During all of this, he was also building a firm that employed and mentored new generations of planning school graduates — many of them from the University of Waterloo.

“It’s one thing to be the best planner in the world, it’s quite another to have that skill set and continue to build the company,” said Bernie Hermsen (BES ‘75), MacNaughton’s first partner. “Ian was able to harness the energies of other people and have a common vision with these people doing the right thing.”

MacNaughton was also willing to give back to his local and provincial community. He chaired the task force that successfully planned the renaissance of Kitchener’s once moribund downtown. He was chair of Canada’s Technology Triangle and a member of the Grand River Conservation Foundation. He served on one of Ontario’s Smart Growth panels and the provinces’ Greenbelt Task Force. Closer to home, he found time to serve as the University of Waterloo’s planner in residence and as a member of the Pragma Council, a university think-tank.

Looking back at it all, a decade after his 2013 retirement, MacNaughton remained grateful for what he and those who worked with him accomplished, and how in their own way they made the world around them a better place.

“Very few people have enjoyed the wonders of life I have,” he said with a smile. “I’ve had a wonderful, wonderful life.”

That boundless positivity – and his rich legacy – will continue to inspire the people who have known him, as well as others who discover his story in the years to come.

Read more

Waterloo co-op student applies engineering and tech skills at Caivan to support purpose-built housing and build land-development expertise

Read more

A Waterloo couple reflects on the campus that shaped their careers, their values, and their love story

Read more

Redefining capstone learning by bringing students, faculty and community partners together to tackle real-world challenges

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.