New method can detect early-stage breast cancer in two minutes

The innovative technology will be cheaper and safer than common cancer diagnostic tools

The innovative technology will be cheaper and safer than common cancer diagnostic tools

By Media RelationsUniversity of Waterloo researchers are pioneering a method to detect breast cancer in women early enough for them to receive life-saving treatment.

The innovative technology aims to be more accurate as well as cheaper to provide than today’s most common diagnostic tools such as X-ray mammography, ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Test runs have been completed in two minutes and used less energy than a smartphone. It would also be safer than X-rays, which expose patients to high-level radiation that can damage DNA and cause cancer.

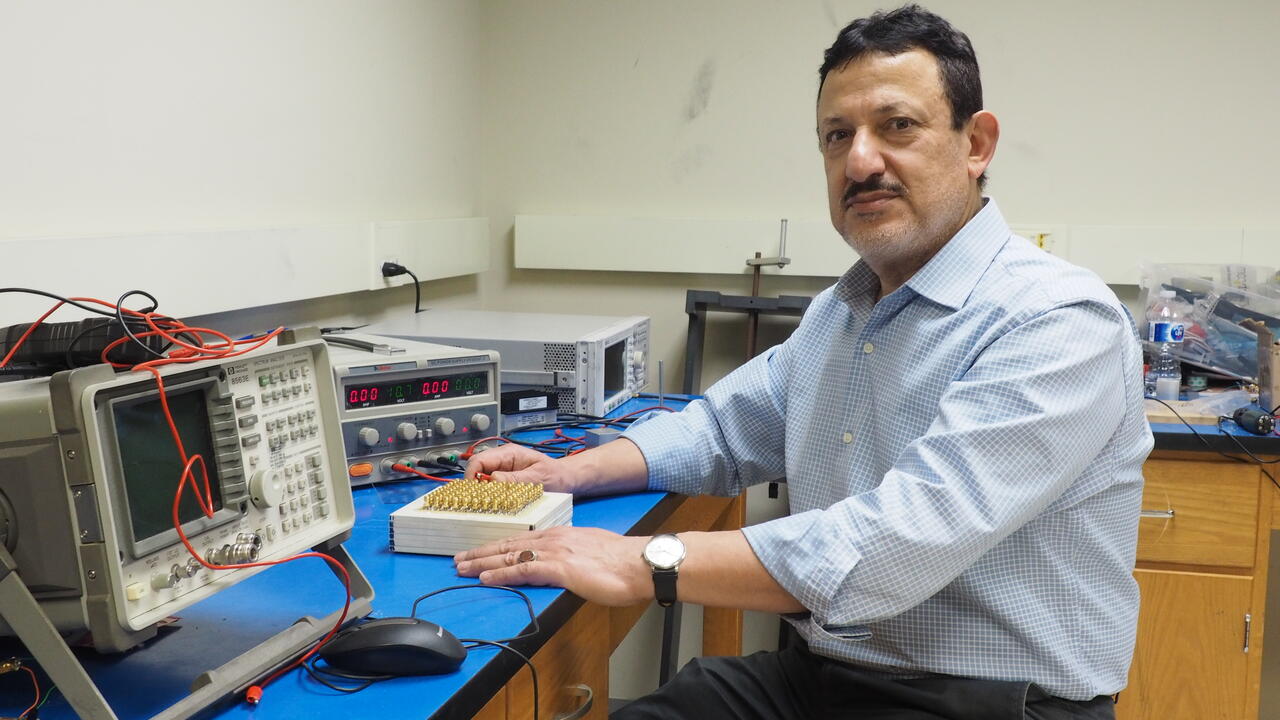

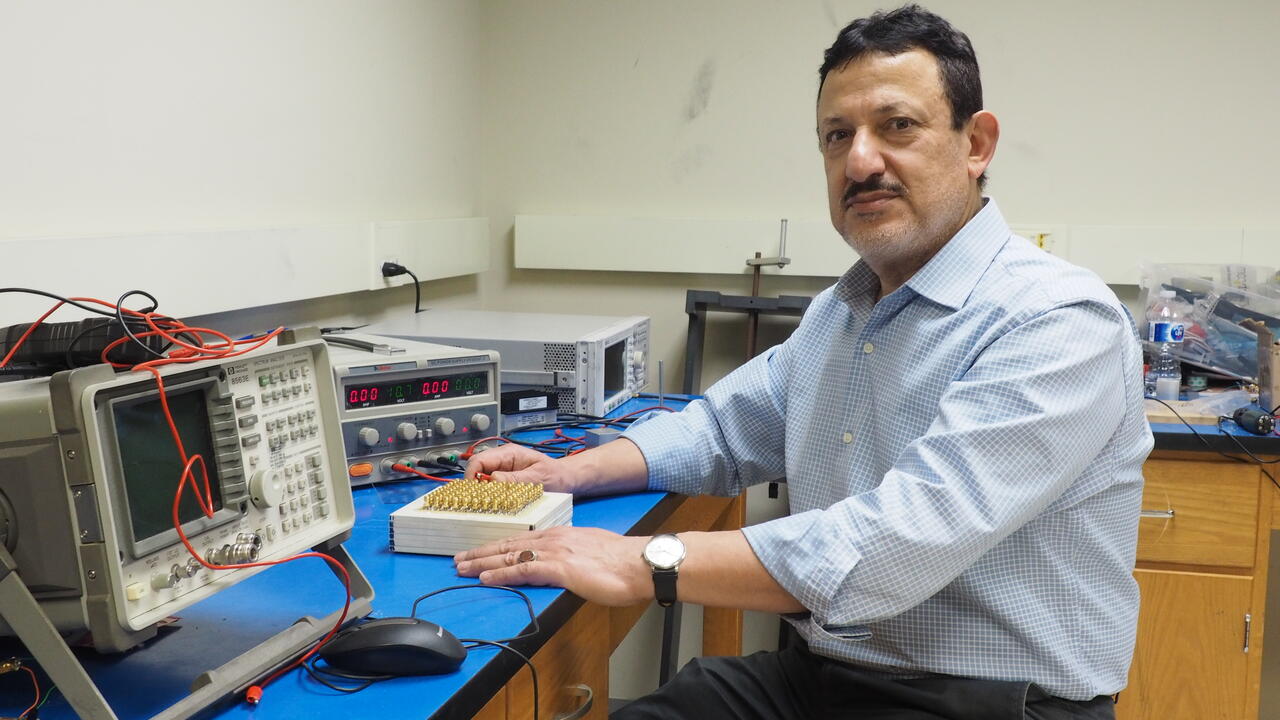

“We are coming very close to providing a method for breast cancer detection at an early stage that is inexpensive and harmless for women,” said Dr. Omar Ramahi, lead researcher and a professor in Waterloo’s Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. “We’re trying to make a serious contribution to women’s health and create an alternative that is clinically and commercially viable.”

Breast cancer is both the second-most common cancer and the second-leading cause of death from cancer for Canadian women. The sooner a malignant tumour is detected, the better a woman’s chance of survival. Ramahi began exploring new ways to detect early-stage breast cancer in 2001 and, for the past five years, has been studying the potential of low-frequency electromagnetic waves.

Ramahi and his research team of current and former Waterloo Engineering students made what he described as “a big discovery,” namely that very low electro-magnetic frequencies “travel in straight lines.” They are the first to have made this discovery, which has allowed them to create the latest disruption to global and individual health care by Waterloo researchers. Building disruptive technologies is at the core of what we do, and since our inception, Waterloo has been disrupting the boundaries of health.

The diagnostic device they created somewhat mimics X-ray mammography but without its drawbacks. In place of X-rays, low-frequency electromagnetic energy is emitted from an antenna, like the one found in a smartphone. Once the energy penetrates a patient’s breasts, it is picked up by a metasurface, or circuit board, consisting of end-to-end pixels, each pixel acting as a receiver.

The AI then interprets the pictures coming from the circuit board, removing the need for a human technician to review the results. The technology can locate the size and location of a tumour, even in breasts with dense tissue, something current diagnostic systems can miss.

Ramahi has tested his system on breast phantoms, which are artificial structures designed to emulate the properties of a human female’s breast. “The results are extremely encouraging,” he said, noting that their technology has no competitors.

The researchers’ next steps are to develop a system that, with approval from Health Canada, can be tested on human subjects. Ramahi is seeking funding from institutions and companies as he develops a prototype for manufacturing his technology. His goal is to create a device that is cheap enough for use in all countries around the world and accessible enough for women to use with the same convenience and frequency as in-pharmacy blood pressure testing.

More information about this work can be found in the research paper, “Mammography using low-frequency electromagnetic fields with deep learning”, published in Nature Scientific Report.

Read more

New medical device removes the guesswork from concussion screening in contact sports using only saliva

Waterloo researcher Dr. Tizazu Mekonnen stands next to a rheometer, which is used to test the flow properties of hydrogels. (University of Waterloo)

Read more

Plant-based material developed by Waterloo researchers absorbs like commercial plastics used in products like disposable diapers - but breaks down in months, not centuries

Read more

Here are the people and events behind some of this year’s most compelling Waterloo stories

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.