Chasing its tail in the cosmos

Astronomers spot massive gas streams flowing from ultra-hot Jupiter that rewrite expectations for these massive giants of space

Astronomers spot massive gas streams flowing from ultra-hot Jupiter that rewrite expectations for these massive giants of space

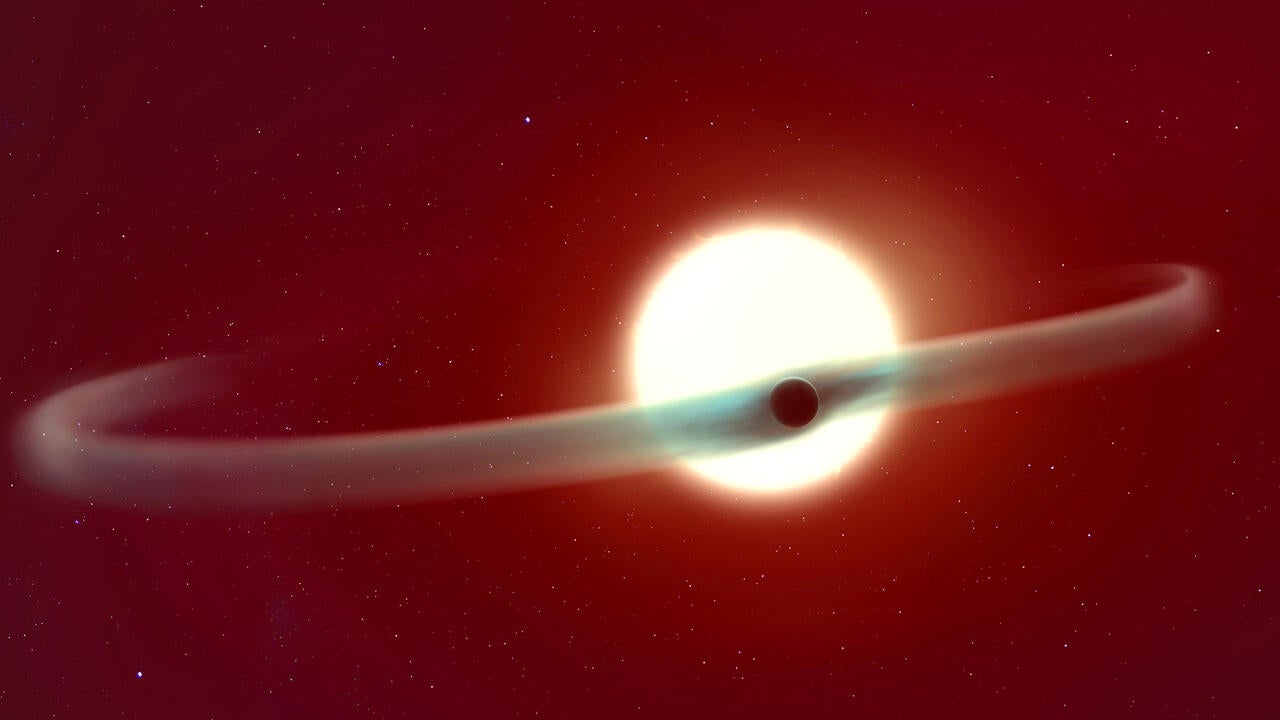

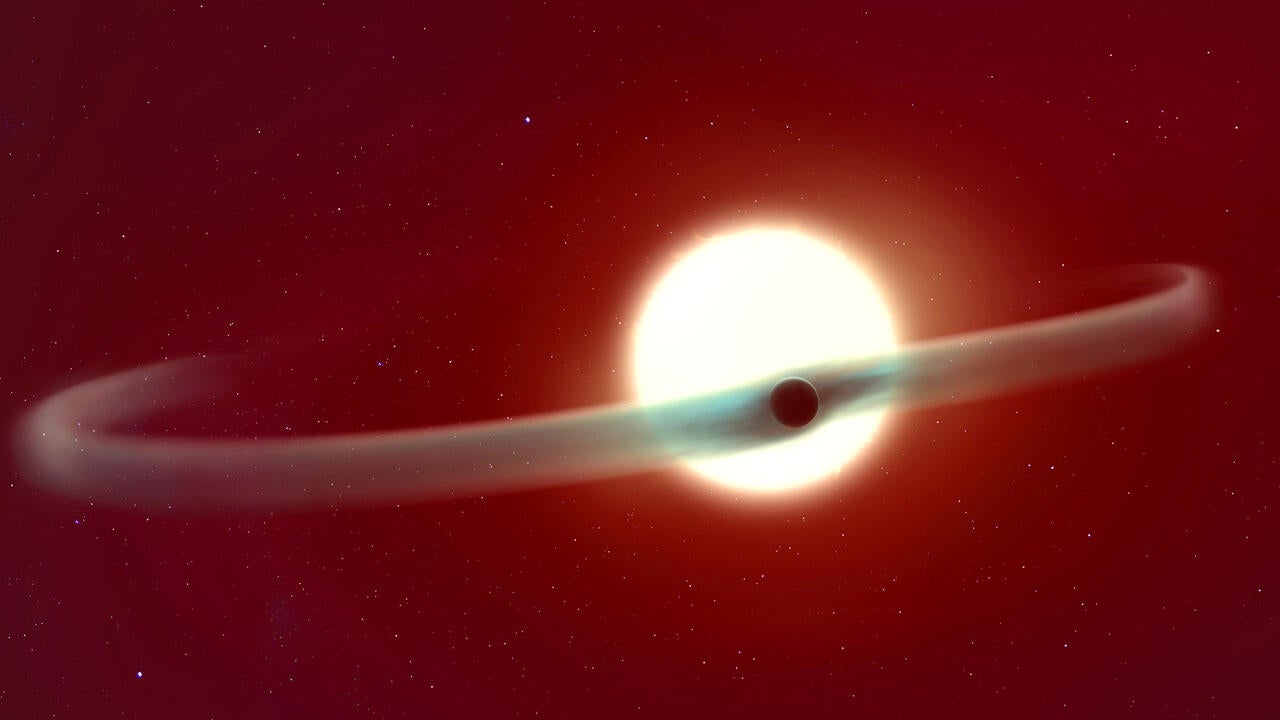

By Katie McQuaid Faculty of ScienceScientists, including Waterloo’s Professor Lisa Dang from the physics and astronomy department, have discovered a huge cloud of helium gas is escaping from the atmosphere of the exoplanet WASP-121 b, an “ultra-hot Jupiter.” Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), scientists found that the helium stretches into long tails in front of and behind the planet as it orbits around its star. The planet is losing atmosphere in dramatic ways, but current models can’t fully explain the observed structure, leaving scientists searching for more information.

An ultra-hot Jupiter, like WASP-121 b, is a massive exoplanet orbiting close to its star with an extremely hot day temperature. It is also tidally locked, meaning the same side is always facing its star, like how the same side of the moon always faces the Earth. The team’s original goal was to observe WASP-121 b to see the difference between the molecules on the dark and the light sides, but when reviewing the data, the team spotted something else of interest.

“There was a very apparent helium signature that stood out when looking at the data,” Dang says. “Normally, when we look at exoplanets, we search for tiny, tiny signals that are buried in the noise. This one was standing out of the noise, almost like it was waiting for us to find it.”

That helium signature showed them that WASP-121 b was a trail of helium covering 60% of its orbit, creating a stream in front and behind the planet it as it moved. Dang worked with the lead authors of the paper on how to depict the helium stream. They were able to look at the data and split it into three parts: ahead of the planet, around the planet, and behind the planet. Then they ran simulations to see what the shape of the full helium stream might be, giving them the banner photo above.

This is the first time scientists have detected important atmospheric loss like this on a Jupiter-sized planet.

“Atmospheric loss of this nature is common for smaller Neptune-sized planets, but planets the size of WASP 121-b have a stronger gravitational pull and are usually very good at keeping their atmosphere intact,” Dang says. “Until now, we didn’t know a hot Jupiter could lose its atmosphere at such a rate so this is a surprising discovery.”

This new observation has sparked excitement in Dang and her colleagues and inspired them to revisit other ultra-hot Jupiter-sized planets to see if they can find something similar or if there is something special about WASP-121 b. Once they find a planet with promise, they hope to observe it further.

“To see whether any other ultra-hot Jupiters have the same helium outputs, we will have to observe them for a full rotation, which means requesting more time on the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST),” Dang says. “Getting 40+hours on the JWST aimed at one star is hard to get approved because the telescope is in such high demand, but I think there is the potential for meaningful science here that we would not be able to do without a long stare with JWST.”

As Dang and her collaborators move into the next phase, she will continue to work with her Waterloo co-op students on extracting more information from the data set they already have.

The paper, “A complex structure of escaping helium spanning more than half the orbit of the ultra-hot Jupiter WASP-121b,” was published in Nature Communications.

Banner image is an artistic representation of exoplanet WASP-121 b showing its impressive double helium tail spanning nearly 60% of its orbit around its parent star. (Photo credit: B. Gougeon/UdeM)

Read more

New evidence-based classification rules expand access and improve fairness for Para Cross Country and Para Alpine skiers

Hand holding small pieces of cut colourful plastic bottles, which Waterloo researchers are now able to convert into high-value products using sunlight. (RecycleMan/Getty Images)

Read more

Sunlight-powered process converts plastic waste into a valuable chemical without added emissions

Dr. Travis Craddock, professor and Canada Research Chair, says the team's findings change our basic knowledge of biology (University of Waterloo).

Read more

New study reveals quantum-level effects in biology with major implications for treatment of some brain diseases

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.