Preserving our digital history

As we increasingly live online, researchers use web archives to find our histories within big data

As we increasingly live online, researchers use web archives to find our histories within big data

By Kaitlin O'Brien Faculty of ArtsThe internet’s cultural record has been growing at an unprecedented rate, accumulating hundreds of billions of webpages. Unless we have a way to retrieve those pages, that history could be lost. Enter Ian Milligan, a professor in the Department of History and an advocate of web archiving. He is exploring petabytes of cultural heritage data and making it accessible to the public.

“Data is rapidly becoming the building blocks of our histories — more specifically the histories of the 1990s and 2000s. We need to establish ways to work with that information,” Milligan says.

With the shift to remote learning and working amidst the COVID-19 crisis, most of our interactions are taking place in online environments, mediated through computer screens, and this includes news websites, social media websites like Twitter and Reddit and university webpages. Milligan presses, “The COVID-19 pandemic underscores just how important the web and web archives will be for historians trying to piece together this global event.”

Throughout his Archives Unleashed project, and research projects preceding it, Milligan and his co-investigators, fellow Waterloo professor and computer scientist, Jimmy Lin, and Nick Ruest, a librarian at York University, developed tools to enable researchers to work with and analyze web archives.

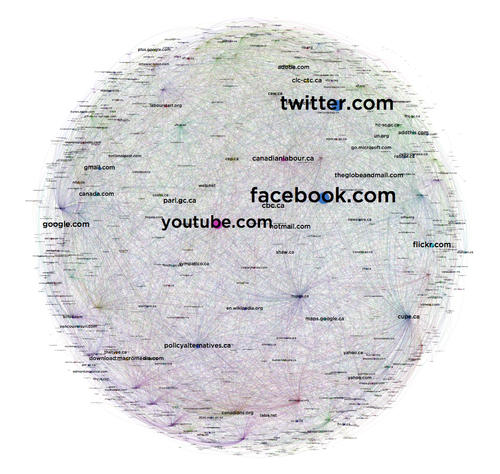

Visualization of the URL links between Canadian political parties and interest groups between 2005 and 2015, letting us reconstruct whole swaths of our political history

Milligan’s interdisciplinary Web Archives for Historical Research Group focusses on the challenge of tackling big data, including how it is reshaping the historical profession. This was also the topic of his recent 2019 book, History in the Age of Abundance. He explains, “We’re experiencing a true shift from historical scarcity, where historians wished we had more information about the past, to one of abundance, where the scale threatens to overwhelm.”

Users of the team’s initial project tool, the Archives Unleashed Toolkit, typed in various, and often obscure, commands to generate their research results, but this meant technical skills were required to perform light programming. To overcome this potential skills gap and to segue into the newest project chapter, the Archives Unleashed Cloud was launched with support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. With a web-based front end that resembles a web application, users can log in, sync their collection from the internet archive and access historical webpages.

Now that the cloud application is a usable tool for researchers, new questions have emerged because historians have access to more data than ever before. For example, History PhD student Sarah McTavish uses Archives Unleashed in her research practice to find individual stories among the data masses rather than obscuring people down to numbers and statistics.

“My own research deals with the LGBTQ community and the ways that they've used the internet to share their own stories and identities and to find others like them,” McTavish says. “The only way to successfully do this kind of research is by using tools which highlight places of interaction and influence, and which allow scholars to examine the stories that people post online, while maintaining the context within which they were writing and sharing.”

In addition to McTavish, Milligan also has other History graduate students that work on learning guides for this project. These learning guides help users navigate the interface and understand the use-cases for web archival research. Building on their work at Waterloo, McTavish has been able to deliver these instructional materials at an in-person international training event at George Washington University.

All of this is part of a broader research agenda to upgrade the digital literacy of humanities scholars. For example, when users search on platforms like JSTOR, Google Books or ProQuest, searches are completed and citations are found, but researchers often don’t reflect on why certain books are digitized, and others aren’t. When this happens, Milligan explains, it conspires to shape the public’s research. Historians and people in the humanities are not that critical about how computers have changed the approach to research.

“Almost no one thinks about why Google is picking those top ten search results for your query. I think about why these forces are influencing our life, and how can we can design infrastructure and tools as historians to tackle and solve this problem,” he says.

What helps this project to flourish in this age of information and big data? Interdisciplinarity.

“I work with librarians and computer scientists to make this work possible,” Milligan says, highlighting his long-term collaboration with Ruest and Lin. “Individually none of us could do this work because of our vastly different skillsets, but together it is possible.”

The goal is to see continuing acceptance and use of web archives among researchers. “Like JSTOR, when scholars use it, they don’t talk about it, they just cite from it,” Milligan says. “I’d like users to access a web archive from our platform, get the information and move on. I’d like Archives Unleashed to fade into the background and become a part of the scholarly landscape.”

Recognizing the need to ensure the COVID-19 cultural record is being preserved, as of May 4th, the Internet Archive’s Archive-It service and the International Internet Preservation Consortium have banded together to preserve over fourteen million documents from over five thousand websites, in forty-two languages. “This is a display of international cooperation to create an international archive of this material, created by governments and everyday people alike,” Milligan says.

Read more about The Archives Unleashed project.

Read more

Researchers have created a software-based system, called Mitigator, that helps Internet users ensure their online data is secure.

Read more

A new, multi-national study will examine whether social connectedness and compassion can help people cope better with the emotional stress of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Read more

Waterloo lab turns remote sensor data into public health information

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.