A robot friend for vision treatment

A social robot could help children and families stick to a treatment for 'lazy eye'

A social robot could help children and families stick to a treatment for 'lazy eye'

By Karen KawawadaIt’s a potentially life-altering medical condition typically diagnosed in childhood. The good news is treatment works well if followed properly. The bad news is the treatment is hard to stick to.

An interdisciplinary team of University of Waterloo researchers is trying to improve treatment adherence through use of a social robot that can educate and motivate children and their caregivers.

The condition is amblyopia, where one eye doesn’t see as well as the other. Though sometimes called ‘lazy eye,’ the problem is with the brain, not the eye. If the problem doesn’t get corrected early enough, permanent vision loss can result, and poor vision in one eye can limit learning, well-being and future career options.

Amblyopia treatment involves patching the stronger eye for two to six hours a day, which can be challenging. When children and parents don’t sufficiently understand the condition or its treatment, it’s easy to give up, because many amblyopic children don’t struggle in obvious ways.

Typically, clinicians briefly explain amblyopia to parents. However, it’s hard for parents to absorb all the information at once and these conversations often don’t engage the child.

Waterloo researchers, who have backgrounds in optometry, engineering and psychology, are developing a social robot they hope will overcome these hurdles.

The idea is that while they’re at an optometry clinic, children and caregivers will spend time with the robot. The robot will interact with family members age-appropriately. For example, a young child could put a patch on the robot’s eye and feel kinship with it, while the robot could show parents through a screen what each of their child’s eyes sees and provide information about amblyopia and its treatment.

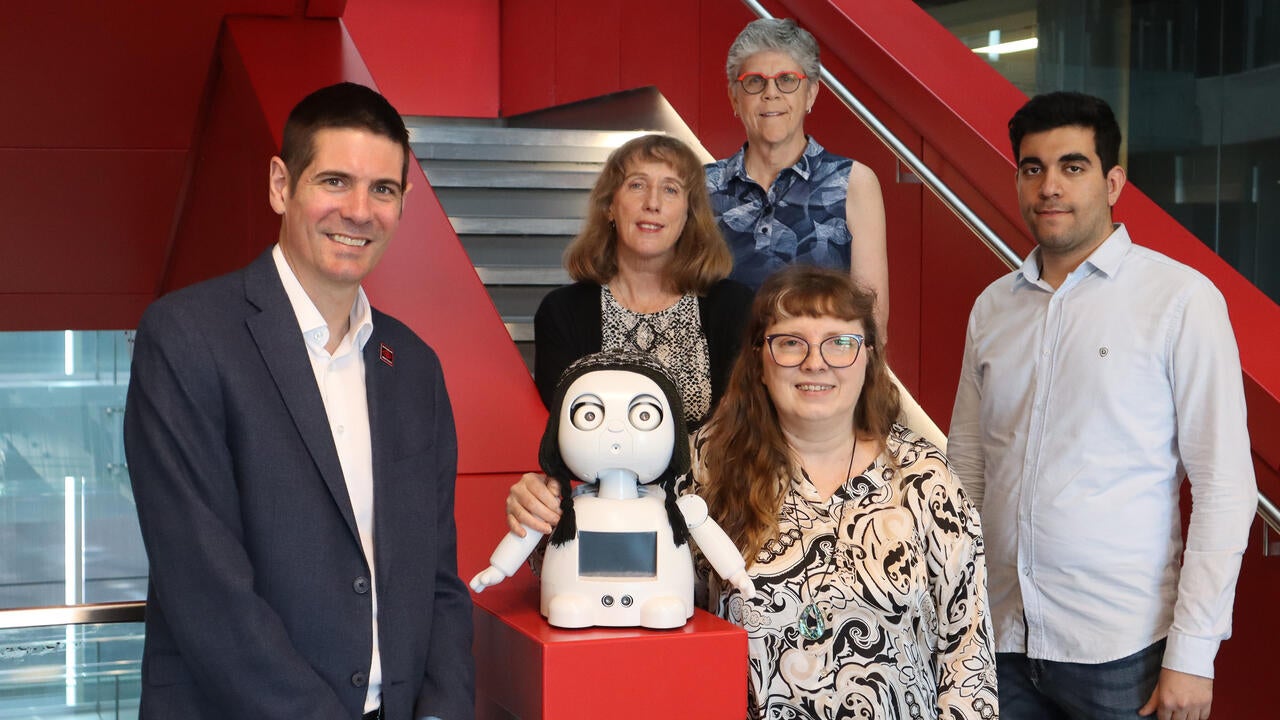

Mirrly, the robot

At home, children and parents will be able to interact with the robot virtually through an online platform providing further information, support and motivation.

“We’ve seen social robots being used effectively in settings such as restaurants but not in eye care,” said Dr. Ben Thompson, a professor at the School of Optometry & Vision Science and the project lead. “This project is proof of concept to see if we can use them effectively for patient education.”

“Compared with using a tablet or computer, there is a lot of research that shows children find working with social robots more enjoyable; they want to interact with them,” added Dr. Kerstin Dautenhahn, a professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. “A robot can motivate and encourage children, so I’m very optimistic that this work will lead to behavioural change.”

The team previously received Graham Seed Fund support to carry out interviews with parents of amblyopic children and create a prototype robot based partly on their input.

Left to right: Dr. Marlee Spafford, Dr. Maureen Drysdale, Dr. Ben Thompson, Ali Yamini and Dr. Kerstin Dautenhahn. Absent: Dr. Lisa Christian.

Now the team has received funding through the New Frontiers in Research Fund of the three federal research funding agencies (CIHR, NSERC and SSHRC) to bring the robot into the clinic and carry out a study with volunteer patients and families. The two-year study will examine patching adherence and changes in children’s vision. Researchers will also observe children and families interacting with the robot and assess their psychological well-being over time.

“Research shows that children with amblyopia experience challenges such as reading difficulties, lowered self-esteem and reduced emotional well-being,” said Dr. Maureen Drysdale, a professor of psychology at St. Jerome’s University. “Robots are exciting for kids, so I hypothesize that engaging with one will be a positive experience – and positive experiences have positive mental health and well-being implications. The robot may also improve parents’ well-being by reducing the pressure on them to make their children adhere to the treatment.”

“If the social robot helps improve treatment adherence, it will help improve vision, and that will make a difference in a child’s life over the long term,” said Dr. Marlee Spafford, a professor emerita of optometry.

The researchers foresee future applications beyond vision.

“If it works for amblyopia, it could be applied to other conditions to help improve health outcomes,” said Dr. Lisa Christian, an associate clinical professor of optometry.

Read more

New Canada Research Chairs will tackle future-focused problems from social robots and intergroup attitudes to geochemistry and nanoscale devices

Read more

The Government of Canada announces funding to support research in health, AI, climate and social equity and drive national innovation

Read more

Six Waterloo students awarded the prestigious Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.