Using mathematical models to make the best cuts in skull surgery

University of Waterloo mathematician helps surgeons operate on children with facial deformities at Toronto hospital

University of Waterloo mathematician helps surgeons operate on children with facial deformities at Toronto hospital

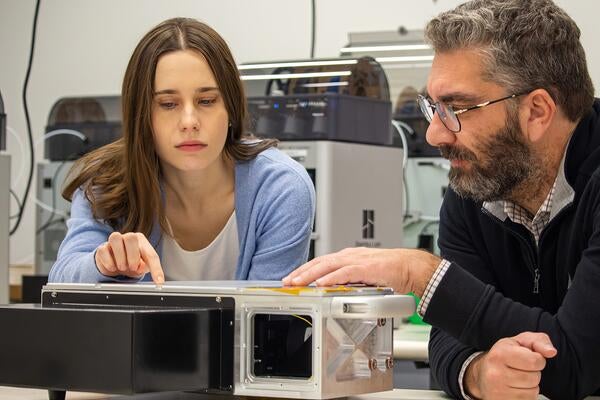

By Anna Beard Faculty of MathematicsAndré Linhares is a University of Waterloo doctoral student who uses mathematical models to help children with facial deformities.

Linhares, a PhD student in the Faculty of Math, is working with surgeons at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children to help ensure the best possible outcome for children who undergo skull surgery.

“We run an algorithm to determine which locations are the best to make the cuts. We send those results to the surgeon prior to the operation. They analyze the results and choose the best model,” said Linhares

“We run an algorithm to determine which locations are the best to make the cuts. We send those results to the surgeon prior to the operation. They analyze the results and choose the best model,” said Linhares

Mathematician spends time in operating room

Interestingly, the mathematical models being used in operating rooms so far are producing very different cuts from the ones the surgeons would have used naturally.

Linhares hopes that by using precise mathematical models to make optimal incisions during surgery, young patients will have better outcomes - which would mean fewer facial deformities after the surgery.

Collaborative research isn’t all roses though – especially when it comes to the health and wellbeing of children. Being able to fully understand how mathematical modeling can be used in surgery meant Linhares found himself in the operating room observing a surgeon remove a strip of bone above a young patient’s eyebrow, called the fronto-orbital band.

The first time, Linhares admits he needed a chair.

Surgery helps children whose skulls fused prematurely

“We went to Sick Kids this year to watch operations. We have very different backgrounds. We study math and they do surgeries so it isn’t always easy to communicate. It was really important to see how the models are being used in surgery,” said Linhares.

Linhares is working with surgeons who operate on children who suffer from a medical condition known as craniosynostosis, which causes an infant’s skull to fuse prematurely. The condition can result in an abnormally shaped skull and facial deformities. It can also affect a child’s cognitive development and vision.

Linhares is working with Ricardo Fukasawa and Jochen Koenemann, both professors in the Combinatorics and Optimization Department in Waterloo’s Faculty of Math.

The research team hopes surgeons will be able to use the models to train surgeons unfamiliar with the process, and also reduce surgery time.

Having only been integrated into the project for a short amount of time, Linhares is looking to put his own spin on the project, which relies heavily on the work done by David Qian, who was a graduate student in Waterloo’s Master of Mathematics program.

Models may be used in more complicated cases

“We already have a method to find the best positions for reconstruction using the fronto-orbital band. What we’re doing now involves validating our method. We still need to analyze those results,” he said.

“The next thing we want to do is to extend it to different types of surgery. The surgeries we’re doing now only use the fronto-orbital band. There are some cranial deformations where surgeons need to make cuts in different areas of the skull. We’re trying to extend it to more complicated cases.”

A car’s exhaust pipe emits black carbon. This sooty form of pollution alters the “light environment” beneath the snow, affecting plant growth. (Kmatija/Getty Images)

Read more

Research into light and snow interactions provides new insights into how pollution can affect vegetation growth and impact ecosystems

Read more

Researchers developed a process to reduce the amount of energy needed to run data centres

Read more

Phantom Photonics’ quantum remote sensing technology offers precision for industries operating in extreme environments

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.