Waterloo grad shares vision of “home” through her art

Jess Lincoln challenges us to consider the space we make our own and the objects we surround ourselves with every day

Jess Lincoln challenges us to consider the space we make our own and the objects we surround ourselves with every day

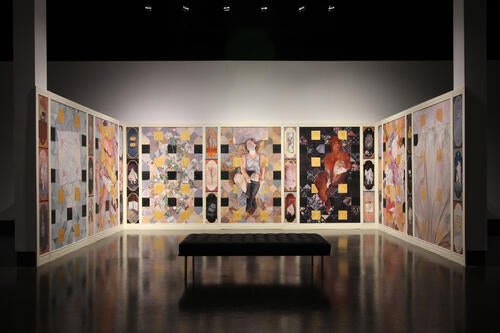

By Claire Prime Faculty of ArtsViewing Jess Lincoln’s art is a bit like stepping into a stranger’s home. A recent exhibition called, An Interior, was a three-sided installation covered in paintings large and small — some of the artist on or under a quilt, others depict objects from a modest home.

It was a busy space; not an inch of bare gallery wall was exposed. Viewing her art causes us to consider the space we make our own, and the objects we use and surround ourselves with every day.

“If you go into someone’s home and see the things they touch and use every day, there’s a vulnerability there. It is a very intimate portrait of someone,” says Lincoln, who graduated from the Master of Fine Arts program in June.

An Interior is a vulnerable work for Lincoln. She has incorporated herself in the work through self-portraits, of her putting on a sock, tangled in fabric or hiding under a sheet. There are paintings of piles of clothing and scattered pink, purple and white flowers. She also appears as a gesturing figure under a bed sheet, like a child dressed for Halloween. She’s incorporated objects from her home along with quilt and floral patterns from her grandmother’s farmhouse.

Lincoln's three-sided Master of Fine Arts exhibit.

Lincoln's three-sided Master of Fine Arts exhibit.

The Saskatchewan farm looms large in Lincoln’s memory as a place where her family gathered for important events. Her grandmother’s identity was deeply tied to the house and the objects she produced in it: clothing, blankets, knitted washcloths, jam and stained glass. “Because the house is imbued with her labour, it is also imbued with what she wanted from all of us. And so being there is to confront that,” writes Lincoln in the written portion of her thesis. “I would not know my family if I did not also know the house.”

Lincoln has a very different relationship to her home than her grandmother did. She has moved so often her apartment is “kind of Value Village minimal,” she says. “I have a few small things that I like to hang up, things that I really think of as being my stuff. It feels like home if it’s got my waving plastic kitty in it.”

The 27-year-old has been on the move since she graduated high school in Calgary. She studied at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, spent a semester in Seoul on an exchange, worked as a custom framer in Halifax, took a job as an interpreter of historical fire trucks in Dawson City, Yukon before moving to Montreal on a whim to learn French when the weather got cold up North. There, she taught English and art at a Chinese community centre and worked at an art supply store before applying to and being accepted into the competitive artist-in-residence program at the Klondike Institute of Arts and Culture in the Yukon. The opportunity to focus on her work inspired her to pursue her master’s degree at Waterloo.

The Master of Fine Arts program offers students a unique opportunity to study for a summer with an artist of their choosing. Through the Keith and Win Shantz International Research Scholarship, Lincoln flew to London, England to work with Sigrid Holmwood, who shares Lincoln’s admiration for the creative work of ordinary people.

Holmwood uses her own handmade paints and dyes sourced from natural ingredients, such as indigo and crushed cochineal insects, to create depictions of peasants, who would have used some of these same ingredients in their art. Under her guidance, Lincoln helped distil paints from vats of bubbling liquids, dyed huge bolts of fabric and hand-sewed medieval costumes for Holmwood to wear.

Besides learning more about materials — paints, dyes and fabrics — and new techniques, the trip offered Lincoln a chance to see the vast array of art in the city, which inspired the design of her installation. She was drawn to the historical painted walls in the houses and public buildings of the very rich. The paintings, though beautiful and ground-breaking at the time, were not always meant to be contemplated; instead, they functioned a bit like wallpaper.

During the first year of the program, MFA students spend the majority of their time learning and teaching. The second half of the program is dedicated to working on their thesis. When Lincoln returned from England, she worked with advisors Tara Cooper and Doug Kirton to refine plans for her exhibit. Over the next eight months, she spent up to eight hours each day painting the 37 panels that make up her installation, which was displayed at the UWAG gallery in April. She relished that time .

.

“Between my degrees, I would want to work but just to be able to find the time and money to pay for it was always a battle,” she says. “To have the time and space to specifically do this and to have people who are really invested in pushing you to improve is immeasurably valuable.”

This summer, Lincoln is working with Cooper on Waterloo’s Student Art Innovation Lab (SAIL), a mobile arts outreach program. A group of artists will take a trailer to community organizations and street festivals and run workshops for children and youth. When she finishes, she hopes to continue teaching and working. Some day, Lincoln would like to cover the walls of an entire house, or maybe just a room, in her paintings.

Read more

A message from the President and Vice-Chancellor Vivek Goel

Read more

Leaders across sectors converged to explore how a collaborative region can turn evidence into coordinated community action

Read more

Every four years, the Olympics and Paralympics propel curling into the spotlight and researcher Heather Mair is working on building and sustaining a more diverse following

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.