Are we all a little guilty of denying climate change?

Our belief in human progress and innovation may be keeping us from taking real action on climate change, says Waterloo expert

Our belief in human progress and innovation may be keeping us from taking real action on climate change, says Waterloo expert

By Elizabeth Rogers Faculty of ArtsIt’s easy to spot traditional climate change denial. Just read the comments on social media or comments from public officials. Deniers say it’s a hoax, a cash grab or a natural process. They’re wrong.

Most data suggests that all but a handful of Canadians accept that human behaviour impacts the climate. But that doesn’t mean we’re past climate denial. According to University of Waterloo environmental humanities professor Andrew McMurry, we’re eager to accept that something bad is happening, but are in denial about what’s actually threatening us and that we need difficult transformative action to beat climate catastrophe.

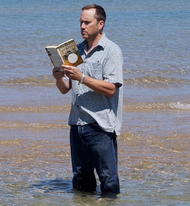

“Our failure to act could be a rhetorical problem,” argues the author of Entertaining Futility: Despair and Hope in the Time of Climate Change. McMurry, who has a background in biology and a long-held interest in conservation, examines how language, narrative and cultural tradition shape our beliefs and understanding about the environment.

“Our failure to act could be a rhetorical problem,” argues the author of Entertaining Futility: Despair and Hope in the Time of Climate Change. McMurry, who has a background in biology and a long-held interest in conservation, examines how language, narrative and cultural tradition shape our beliefs and understanding about the environment.

And it’s never been more crucial. Nearly everything we do — the food we eat, the goods and services we rely on — produces greenhouse gases. Trying to fix this problem requires a top-down reordering of how we live, especially how we produce and consume energy.

So why aren’t we doing it?

“There’s a level of contradiction that yes, we know we need to do something, but we’re not actually doing anything. Because maybe we feel that it’s not really that scary,” says McMurry.

It is scary.

A recent report revealed that Canada is warming at twice the global rate. And while some believe a warmer climate could benefit us here in Canada, McMurry notes the impacts of climate change will be felt by the wicked, unpredictable ecological and social problems it will cause. These are big social problems that need collective solutions.

“People imagine an incrementalism where it gets a little warmer and a little warmer, and instead of growing hard wheat up in Alberta, we can grow corn and maybe rice someday,” says McMurry. “It doesn’t work like that. You need predictability, you need water, you need all kinds of things to be in the right balance. That way of thinking ignores the unpredictability of climate change. It’s really climate chaos and none of it is working in our interests.”

“Climate will increasingly play a role in every problem we face,” says McMurry. For instance, there will be mass migrations of people as their countries become unlivable, thanks to unbearable temperatures, poorer growing conditions or rising sea levels. The world is already struggling to cope with immigration, and reactionary movements like populism pit groups against each other for political agendas.

“Yet it’s very hard to persuade folks of the need to act decisively and massively when not only their pay cheques but their whole way of life, all their hopes and dreams, depend on them not being persuaded,” says McMurry. "Effective action to slow or mitigate climate change demands a reconfiguration of every aspect of our collective existence, from economy to politics to everyday life."

“We believe in the existence of climate change, but at the end of the day, we prefer to believe it’s not actually going to affect us adversely. We've developed a near-hardwired faith that something will come along to save the day at the 11th hour,” says McMurry. “So many of our cultural narratives take that same approach: in the end something will save us; there is some sort of game-changer out there that we don’t know about; or, no matter, we’ll adapt somehow. Even the bleakest novels and films relentlessly depict humans overcoming obstacles and almost without exception end with a promise of renewed hope.”

It’s not just fiction — our history can be viewed through the same lens. Peace follows war, the ozone layer is repairing itself, and humans programmed their way out of the Y2K problem. While some argue that having hope is a good thing, optimism may be working against us.

“And it’s doubly hard to persuade folks out of denialism when they have, throughout their entire lives, in a million different ways, been persuaded to believe in fantasies like the inevitability of human progress and our endless capacity to solve unsolvable problems, says McMurry. “It’s a really powerful non-motivator.”

If our unfailing optimism is part of the problem, then perhaps a dose of pessimism might be the antidote.

“More than hope, perhaps what we need now is a powerful and bracing fear,” says McMurry. “One productive possibility of a pessimistic worldview is that when you reach the end of the naïve hope and deceptive expectations that knee-jerk optimism provides, you start to come to grips with reality.”

Though McMurry considers collectively implemented solutions as crucial for real action on climate change, he also acknowledges value in grappling with it as individuals.

“I think perhaps pessimism, far from leading to despair and cynicism and a ‘whatever’ attitude, can actually lead to bold action. Now, what you do is done because it’s the right thing to do. It aligns with your best vision of yourself. Uncertainty in the results of your efforts doesn’t mean you should stop trying.”

Read more

To meet our AI ambitions, we’ll need to lean upon Canada’s unique strengths

Read more

New research from the University of Waterloo centres Haudenosaunee-led efforts in the repatriation and reclamation of cultural and intellectual property

Read more

Researchers awarded funding to investigate ecology, climate change, repatriation, health and well-being through cultural and historical lens

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.