Artists respond to the legacy of residential school

The Mush Hole Project is an art and performance event at the former Mohawk Institute Indian Residential School in Brantford

The Mush Hole Project is an art and performance event at the former Mohawk Institute Indian Residential School in Brantford

By Claire Prime Faculty of ArtsA former residential school for First Nations children in Brantford, Ont. — a site where children were physically, sexually and emotionally abused for more than 140 years — has become a space where artists will help visitors connect to the stories of pain, trauma, survival and empowerment.

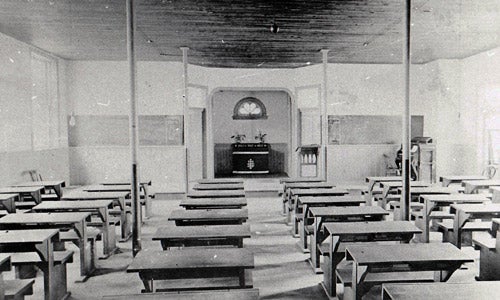

The Mush Hole Project is an art and performance event held on Sept. 16-18 inside and on the grounds of the former Anglican residential school building. Some of the First Nations artists are the children or grandchildren of the school’s survivors and organizers hope the immersive experience will help audiences connect to a dark part of Canadian history.

“It’s not only way up in Kashechewan, it’s right here,” says Professor Andrew Houston of the University of Waterloo’s Department of Drama and Speech Communication. “You’re walking through it, you’re smelling it, you’re feeling it, you’re engaged with it.”

From 1828 to 1970, indigenous boys and girls from across the country were sent to the Mohawk Institute Indian Residential School, a place the students nicknamed Mush Hole after their breakfast — porridge — which was often rancid and so thick a spoon would stand up in it.

The project, led by Houston and Sorouja Moll, a Speech Communication instructor with the university, in collaboration with the University of Waterloo, Waterloo Aboriginal Education Centre, several art galleries and many community groups and individuals, was produced in response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action.

The event aims to respond to the legacy of the school and support efforts by the Woodland Cultural Centre to preserve the building, one of fewer than 10 residential schools still standing across Canada. The project also fosters dialogue and collaborations between indigenous and non-indigenous communities.

“It’s giving Canadians like myself a chance to understand that history, which has been for the most part denied to us,” says Houston.

When Mush Hole Project organizers put out a call for those who had been touched by the school, they heard from artists from across the country. Since it was believed that children wouldn’t run away if they were far from home, students were sent to the Mohawk Institute from across Ontario and beyond; they were Oneida, Cree, Ojibwe and Algonquin, among others.

The installations and performances explore themes including education, nourishment, truth and reconciliation. Visitors travel through the school as they encounter artwork, including sculptures, found objects, video and live performances. Residential school survivors, or their children or grandchildren, are guides who share their personal stories. One installation uses deconstructed sleeping bags, an object used on vacations by many Canadians, and for survival by First Nations people who find themselves homeless. Another explores themes of incarceration and invisibility.

Houston and Moll have also contributed artistically to the project. Moll’s installation, Turning Tables: Recommendations to the Government of Canada, gives Indigenous people space to respond to the “Report on Industrial Schools for Indians and Half-Breeds,” a set of recommendations sent to the government by Nicholas Flood Davin in 1879. Enduring the consequences of government polices, how do First Nations people imagine concepts such as truth and reconciliation? How can this history be reconciled? Two birch wood panels, side by side, will be offered with paint and brushes for audience members from Indigenous communities to convey the complex meanings.

“I wanted to see those decision-making boardroom spaces shifted and transformed, in a sense, and have First Nations people, Six Nations, intergenerational survivors of residential schools present and acknowledged,” says Moll. “What are their recommendations? They weren’t consulted when this was created.”

Houston has created a performance that will take place in the shower space in the basement of the school. Two actors will perform in Sub-Merge, Brook Barnes, a University of Waterloo theatre student, and Andrew Martin, a Mohawk actor from Six Nations whose grandparents attended the Mohawk Institute. Barnes and Martin play two young people of different cultural backgrounds, a non-indigenous woman and her indigenous friend who suffers from intergenerational trauma. The story is based on four accounts of abuse, from as early as the 1920s to as recent as the 1960s, that occurred in the shower space.

“To me, it’s a site of a particular point of violation because when you’re in a place like a bathroom, you’re vulnerable,” says Houston. “It was a place of notorious abuse.”

Houston specializes in site-specific performances and encouraged the actors and production manager Zach Gungl, also a Waterloo theatre student, to spend as much time as they could inside the school.

When you’re in a place with so much history, “it can really be felt,” says Houston. “It isn’t just about semiotics, it isn’t just about communication; it’s actually about a felt dimension, because you’re really in the space of a wound.”

Visit Mush Hole Project for more information.

Read more

GreenHouse awards $10,000 to student ventures and changemakers aiming to transform livelihoods within disadvantaged communities

Read more

Waterloo welcomed distinguished Indigenous architect and scholar to discuss the concept of two-eyed seeing for societal transformation at the 2024 Hagey Lecture

Read more

Waterloo welcomes emerging postdoctoral scholars to receive funding from Provost fellowship programs

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.