Search results influence people’s decisions about treatment effectiveness

Bad information is worse than no information at all.

Bad information is worse than no information at all.

By Joe Petrik David R. Cheriton School of Computer ScienceWe’ve all done it — felt a cough, headache or fever coming on, then searched for a remedy. If you’re like most people, you’re probably confident you can assess the effectiveness of treatments you find on the web, separating medically beneficial ones from those that are a waste of money, dubious or even harmful.

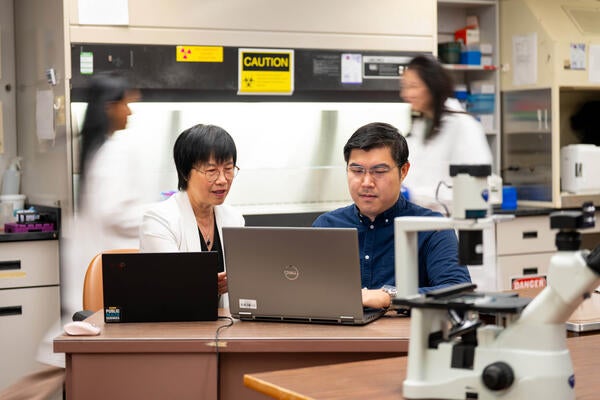

But a recent study by PhD candidate Amira Ghenai at the David R. Cheriton School of Computer Science should give pause to anyone who thinks assessing online health information is easy.

But a recent study by PhD candidate Amira Ghenai at the David R. Cheriton School of Computer Science should give pause to anyone who thinks assessing online health information is easy.

“We found that search results have a significant effect on people’s ability to make correct treatment decisions,” Ghenai says. “In short, finding bad information is worse than having no information at all.”

To determine this, Ghenai conducted a study on 60 Waterloo students in which the search results participants saw were intentionally biased toward correct or incorrect information for 10 medical treatments.

“We chose treatments that are commonly searched for, such as is cinnamon helpful for diabetes, are insoles helpful for back pain, does caffeine help alleviate asthma,” she said, adding that they asked participants to pretend they had a question about the effectiveness of a treatment, followed by an online search to help them answer it.

For each treatment, participants were shown a search page with 10 results modelled after what they would see if they had used Google or Bing. Each result had a document title, a snippet of text and a URL to a page.

“To bias search results towards correct information, we selected eight results to be correct and two to be incorrect,” Ghenai explained.

A correct result was classified as a document that contained information about the efficacy of a medical treatment supported by medical evidence, and an incorrect result was one that was contradicted by medical evidence.

To bias search results towards incorrect information, they did the opposite — selected eight results to be incorrect and two to be correct. As a control, participants were asked to answer whether a treatment was helpful, inconclusive or unhelpful without being shown any search results.

“When search results were biased towards correct information, it increased participant accuracy from 43 per cent to 65 per cent. And when results were biased towards incorrect information, it cut participant accuracy almost in half, from 43 per cent to 23 per cent.”

The influence of incorrect information is concerning because sometimes the condition for which people seek treatment is much more serious than whether insoles can alleviate back pain, and the outcome of an incorrect decision can be grave.

Perhaps the most infamous example of misleading search results is that experienced by Wei Zexi, a Chinese student who died from synovial sarcoma. In the early stages of his cancer, doctors used chemotherapy and radiation, but when traditional treatments no longer helped, Zexi looked online for other treatments. He found a hospital that claimed to offer an experimental cancer treatment, but after receiving the treatment, which cost 200,000 yuan ($41,000 CDN at today’s exchange rates) he discovered it was neither effective nor experimental.

Zexi found the hospital offering the treatment using Baidu, a common search engine in China. He later learned from a friend using Google outside China that there was no scientific evidence the treatment would help. The Baidu search did not reveal that the result was a paid advertisement rather than the result of an organic search.

“When search engines mix correct with incorrect information, we have shown there is potential for significant harm. And when people are desperate, they might see what they want to believe.”

A nurse checks the blood pressure and heart rate of a woman as both sit on a bed. Researchers have found that estrogen’s ability to relax blood vessels plays a key role in protecting women from high blood pressure and may inform more effective treatments after menopause. (Getty Images/ Happy Kikky)

Read more

New research sheds light on why premenopausal women face lower hypertension risk and what that means for treatment after menopause

A car’s exhaust pipe emits black carbon. This sooty form of pollution alters the “light environment” beneath the snow, affecting plant growth. (Kmatija/Getty Images)

Read more

Research into light and snow interactions provides new insights into how pollution can affect vegetation growth and impact ecosystems

Read more

How machine learning empowers collaboration between computer science, math and medical research

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.