Waterloo student helps deliver babies in Uganda

Work term in a country where mothers die in childbirth everyday, affirms Waterloo student’s dream of becoming a doctor

Work term in a country where mothers die in childbirth everyday, affirms Waterloo student’s dream of becoming a doctor

By Christine Bezruki Applied Health SciencesWhen Christina Marchand went to Uganda last summer on a work term, she expected to be doing administrative work for a non-profit organization. By the time she boarded a flight back to Canada, she had helped deliver more than 200 babies.

“I haven’t really had a chance to process it,” Marchand says of the experience. “In Canada we lose 16 mothers a year due to birth-related complications. In Uganda, they lose more than 16 a day. I did what I had to do to help.”

“I haven’t really had a chance to process it,” Marchand says of the experience. “In Canada we lose 16 mothers a year due to birth-related complications. In Uganda, they lose more than 16 a day. I did what I had to do to help.”

Lack of skilled birth attendants for African mothers

A fourth-year health studies student, Marchand sought out her own work term with Save the Mothers, an organization that seeks to improve the health of mothers and babies in developing countries.

Although the organization typically only offers work placements to university graduates, they made an exception for Marchand.

“I was incredibly persistent. I wanted this placement,” says Marchand, who first learned of the organization through a family friend who had spent time in Africa.

Her tenacity paid off. In April, she was invited to Uganda to help with administrative work for the organization’s Master of Public Health Leadership program run in collaboration with United Nations University.

While she found her placement work fulfilling, it wasn’t long before the prospective medical student found her way to a local clinic.

“I waited a few weeks before going into a clinic, because I knew I had to prepare myself for what I would see,” says Marchand.

She was right.

Student learns from midwife

In Uganda, 97 percent of health facilities do not offer emergency obstetric care services. A shortage of medical staff and a lack of facilities means about half of all African women don’t have a skilled birth attendant at their delivery.

The night Marchand walked into the clinic there was one midwife on duty and three women in labour. Ready or not, she knew she had to help.

Under the watchful eye of the midwife, Marchand learned how to deliver a baby, give an episiotomy and even conduct a cesarean section.

“I was nervous,” says Marchand recalling her first time delivering a baby. “But the midwife said, ‘If you weren’t here, there would be nobody.’ I had never thought of it like that.”

As Marchand’s confidence grew, so did her hours at the clinic. She began working days at the university and evenings at the clinic. Sometimes she would deliver 16 or 17 babies in one evening, often under less than ideal conditions.

“There were instances when women couldn’t receive surgery because we were out of supplies. In Uganda something like a supply of rubber gloves can mean the difference between life and death. It’s horrible, but it’s reality,” she says.

Yet Marchand was astounded at the strength of the women who arrived at the clinic. Many had travelled for days.

“The strength of the women and the Ugandan people is amazing. It reaffirmed my passion for medicine, reaffirmed why I want to help.”

Now back in Canada and applying to medical schools, Marchand has plans to someday return to Uganda.

“I know I’ll be back at some point. Africa touches you in a way and doesn’t let go.”

Read more

Here are the people and events behind some of this year’s most compelling Waterloo stories

Read more

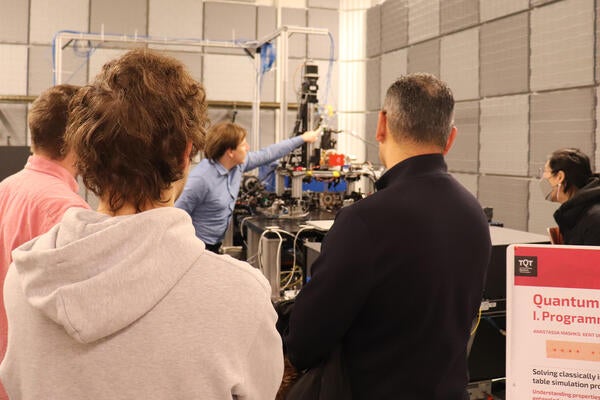

TQT Quantum Opportunities and Showcase sheds light on quantum research advancements, discoveries and real-world applications

Read more

Kicking off Global Entrepreneurship Week by looking at some Waterloo founded companies making a global impact

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.