Battery-free smart devices closer to reality

Computer scientists hack RFID tags, giving them the ability to sense their environment.

Computer scientists hack RFID tags, giving them the ability to sense their environment.

By Joe Petrik Cheriton School of Computer ScienceResearchers at the University of Waterloo have taken a huge step towards making smart devices that do not use batteries or require charging.

Professor Omid Abari, Postdoctoral fellow Ju Wang, and Professor Srinivasan Keshav from Waterloo’s Cheriton School of Computer Science have found a way to hack radio frequency identification (RFID) tags to create battery-free devices. The ubiquitous squiggly ribbons of metal with a tiny chip found in various objects like library books or on the back of cosmetics are commonly used to track inventory in warehouses and factories, prevent theft of merchandise in stores, in bank cards to make contactless payment possible, and even in pets who are microchipped.

“It’s really easy to do,” said Ju Wang, a post-doctoral fellow at Waterloo’s Cheriton School of Computer Science. “First, you remove the plastic cover from the RFID tag, then cut out a small section of the tag’s antenna with scissors, then attach a sensor across the cut bits of the antenna to complete the circuit.”

These battery-free objects, which feature an IP address for internet connectivity, are known as Internet of Things (IoT) devices. If an IoT device can operate without a battery, it lowers maintenance costs and allows the device to be placed in areas that are off the grid.

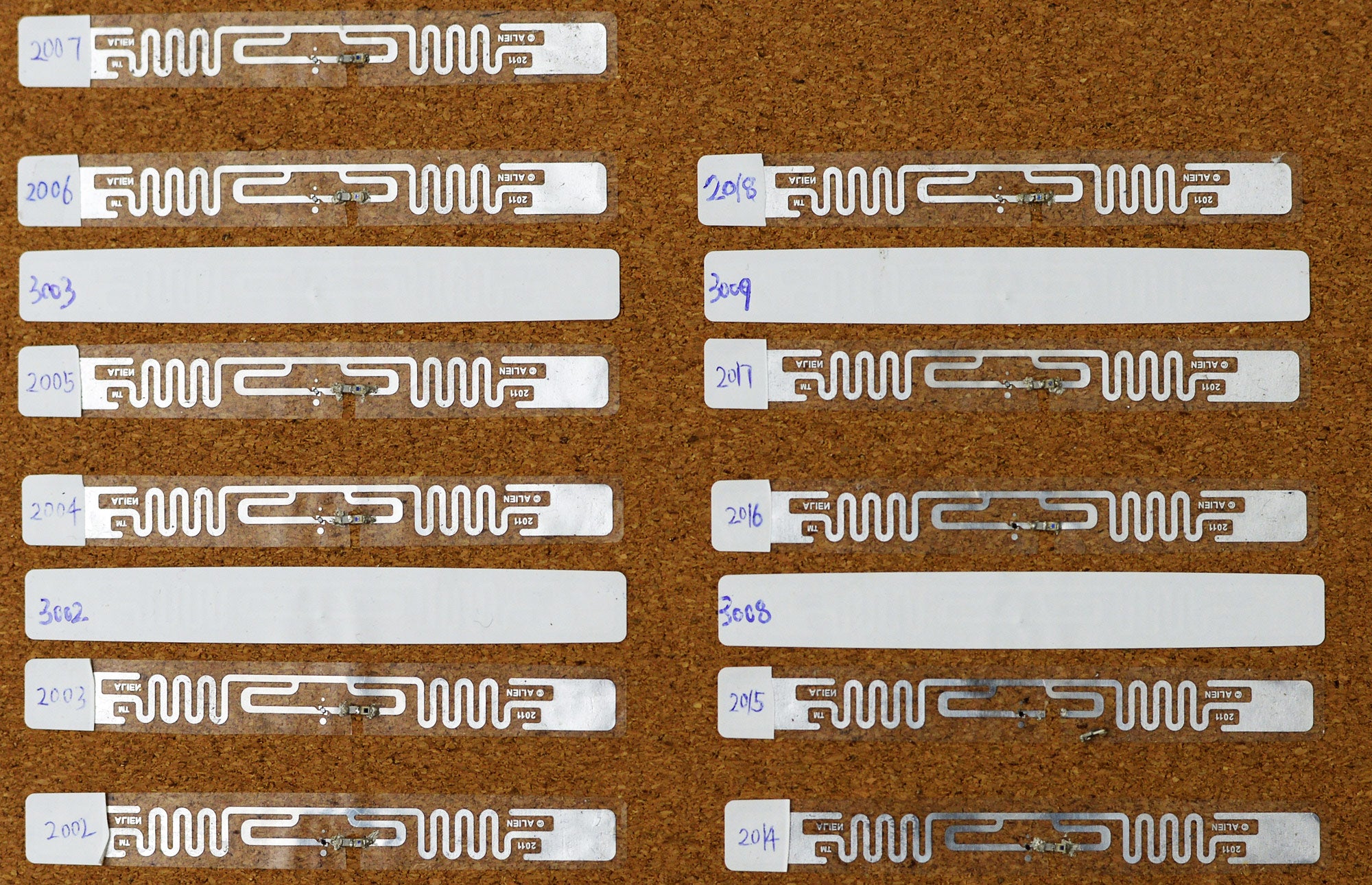

An RFID tag is modified by cutting out a small part its antenna (silver ribbon) and placing a small light-sensing phototransistor or temperature-responsive resistor (thermistor) on it.

In their stock form, RFID tags provide only identification and location. It’s the hack Abari’s team has done — cutting the tag’s antenna and placing a sensing device across it — that gives the tag the ability to sense its environment.

To give a tag eyes, the research team hacked an RFID tag with a phototransistor, a tiny sensor that responds to different levels of light.

By exposing the phototransistor to light, it changed the characteristics of the RFID’s antenna, which in turn caused a change in the signal going to the reader. They then developed an algorithm on the reader side that monitors change in the tag’s signal, which is how it senses light levels.

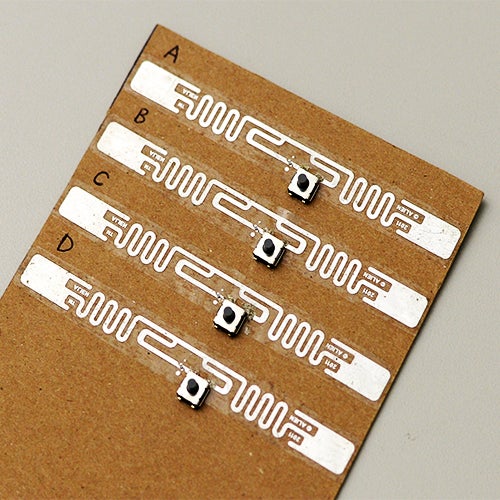

Among the simplest of hacks is adding a switch to an RFID tag so it can act as a keypad that responds to touch.

“Many classrooms have clickers that students use to answer questions or to indicate a choice,” Wang said. “These clickers need a battery to operate. We created a batteryless clicker by cutting the RFID’s antenna and connecting a push-button switch across the gap. You can use several of these modified RFIDs — one for option A, another for option B, yet another for option C, and so on.”

The method is cost-friendly too.

An RFID tag is modified by cutting out a small part its antenna (silver ribbon) and placing a small push-button switch on it. If several modified tags are mounted on a surface, they can act as a wireless keypad.

“We see this as a good example of a complete software-hardware system for IoT devices,” Abari said. “We hacked simple hardware — our main contribution is showing how simple it is to hack an RFID tag to create an IoT device. It’s so easy a novice could do it.”

The research paper by Wang, Abari and Professor Srinivasan Keshav titled, Challenge: RFID Hacking for Fun and Profit-ACM MobiCom, appeared in the Proceedings of the 24th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking, October 29–November 2, 2018, New Delhi, India, 461– 70.

Banner image: Postdoctoral fellow Ju Wang (centre) and Professor Omid Abari demonstrate the wireless keypad clicker they invented by hacking RFID sensors with tiny push-button switches.

Read more

Here are the people and events behind some of this year’s most compelling Waterloo stories

Read more

Biostatistics professor and serial winner Michael Wallace on maximizing your odds in annual Tim Hortons contest

Read more

Five-storey, 120,000-square-foot building will connect mathematical disciplines and advance green computing

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.