Science fiction becomes fact with 3D printed bones

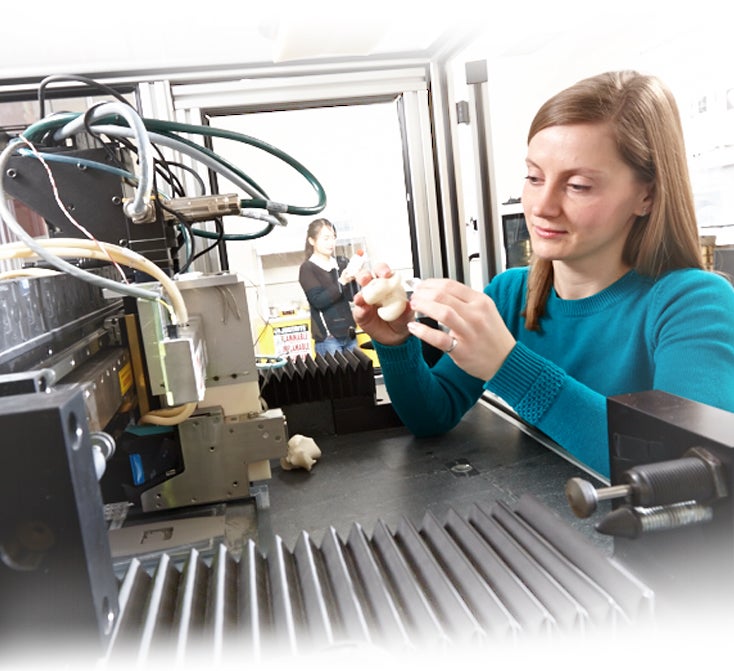

Mihaela Vlasea is exploring an innovative way to address faulty joint replacements that incorporates the use of a 3D printer to develop custom implants, using a calcium polyphosphate powder

Mihaela Vlasea is exploring an innovative way to address faulty joint replacements that incorporates the use of a 3D printer to develop custom implants, using a calcium polyphosphate powder

By Kira Vermond Faculty of EngineeringAnyone who has ever hobbled around on bad knees knows how painful and debilitating it can be. Immobility can last for years before an orthopedic surgeon removes damaged bone and cartilage and replaces it with an artificial joint crafted from metal alloys or polymers.

The pain and recovery time becomes even worse if those implants need to be replaced years later.

Mihaela Vlasea, a post-doctoral researcher and lecturer, is exploring an innovative way to address faulty joint replacements that incorporates the use of a 3D printer to develop custom implants, using a calcium polyphosphate powder.

Not only does the resulting piece behave similarly to bone, the implant is actually bio-absorbable – the body uses it to create fresh tissue.

Hello new real knees. Goodbye metallic joints that last only 10 to 15 years.

Vlasea is a leading member of the team of researchers at the University of Waterloo headed by Ehsan Toyserkani, a mechanical and mechatronics professor. She says the past six years spent working on the project have been exhilarating, but incredibly challenging as well.

“For my PhD I designed a new additive manufacturing machine (known colloquially as a 3D printer) from scratch. That was really tough and at times I didn’t think I could do it,” the mechatronics engineering graduate admits now. “But the meetings we had with the team made me see where the project was going. It was inspiring.”

That team is a partnership that includes orthopedic surgeons, pathologists and students from Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto, materials specialists from the University of Toronto’s dentistry department with a knowledge of calcium polyphosphate and how to treat it with heat, and even a veterinarian surgeon from the University of Guelph.

Vlasea says knowing she was going to work collaboratively influenced her decision to pursue her PhD after completing a BASc in mechatronics engineering at Waterloo in 2008. Her biggest initial fear was that she’d be trapped with a research project with no influence on the real world. That worry was quickly put to rest.

“It’s a dynamic group. Ideas flow fast and we always have a purpose in mind when we’re designing implants and processes for additive manufacturing. It makes the project relevant,” she says.

That shared approach to learning is something she grew accustomed to back in her undergraduate years. She was encouraged to take courses in systems and mechanical engineering, which gave her a wide-angle outlook on engineering. The spirit of collaboration is also strong within Waterloo Engineering today. She says she feels comfortable approaching any professor or graduate student to ask for advice or to run an experiment.

With Vlasea crafting the final two sheep implants now, and with human testing on the horizon, aching knees, hips, shoulders and ankles may soon get long-lasting relief.

Read more

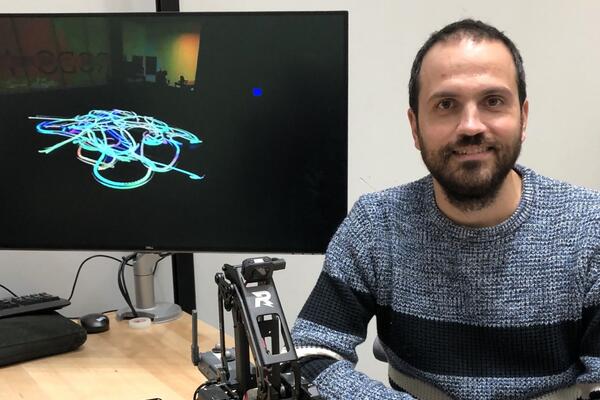

Robots the size of a soccer ball create new visual art by trailing light that represents the “emotional essence” of music

Read more

Waterloo prof leads a team of researchers to improve water quality through a community-focused approach underpinned by technical excellence

Read more

New medical device removes the guesswork from concussion screening in contact sports using only saliva

Read

Engineering stories

Visit

Waterloo Engineering home

Contact

Waterloo Engineering

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.