Making a breakthrough in bricks

Engineering student impresses judges with carbon-neutral masonry units formed using bacteria

Engineering student impresses judges with carbon-neutral masonry units formed using bacteria

By Brian Caldwell Faculty of EngineeringA project inspired by a co-op work term on a construction crew has put a Waterloo Engineering student in the running for an international invention prize.

Adrian Simone, who is in his fourth year of the civil engineering program, was announced today as a national runner-up in the 2022 James Dyson Award competition for a proposal to make bricks using bacteria.

Bio-Brick, the project entered by startup MicroBuild Masonry, is now up against student inventions from 28 other countries for two top prizes of US $45,000. A short list of 20 international finalists will be announced in October from an initial field of almost 1,700 entries.

Simone was doing a co-op term as project manager for a crew laying asphalt when he was struck by the apparent impact of the hot, dirty work on the health of the workers.

“I started thinking there has to be a better way to do this,” he recalled.

Several pivots and iterations later, Simone is now working on a process that uses recycled aggregate and a natural microbial process to form it into masonry units with the same strength and durability as regular bricks.

Bio-Brick tackles two problems at once by reducing carbon emissions from production, a significant issue in the construction supplies industry, and the need for new raw materials in a carbon-neutral solution.

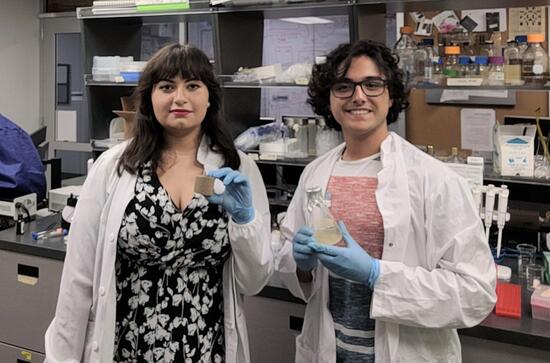

Rania Al-Sheikhly (left) and Adrian Simone co-founded MicroBuild Masonry, a runner-up for the national James Dyson Award for student inventions.

“The solution came from research on self-healing cement where microbes were used to fill gaps in cracked concrete,” Simone explained in his submission. “By readjusting this process we can create supplies with similar properties and a competitive price that makes the manufacturing process completely sustainable.

“There is a microbial process in which certain bacteria, in the right conditions, can create stone out of easy-to-find minerals. These bacteria are suspended in an aggregate and saturated using these minerals suspended in water.”

Waterloo Engineering has a long track record of success in the annual competition, which was launched by James Dyson, inventor of the popular bagless vacuum cleaner, to challenge university students to develop innovative products that solve problems.

“Young design engineers have the ability to develop tangible technologies that can change lives,” he said. “The James Dyson Award rewards those who have the persistence and tenacity to develop their ideas.”

Last year, two recent nanotechnology engineering graduates of Waterloo Engineering – Anneke van Heuven (BASc ’21) and Elias Trouyet (BASc ’21) – made the list of 20 international finalists for a flame-retardant product inspired by seaweed and that they pursued with a startup company called AlgoBio.

MicroBuild Masonry, which was co-founded by Rania Al-Sheikhly, a master of business, entrepreneurship and technology (MBET) student at Waterloo, previously enjoyed success in pitch contests through the Velocity incubator and the Conrad School of Entrepreneurship and Business.

"Having exposure on this level is incredibly helpful," Simone said of its success so far in the Dyson contest. "It tells us that what we are doing is something that people are interested in learning about and that can lead to a lot more opportunities."

Main photo by Andre Moura from Pexels

Read more

Two University of Waterloo affiliated health-tech companies secure major provincial investment to bring lifesaving innovations to market

Read more

How Doug Kavanagh’s software engineering degree laid the foundation for a thriving career in patient care

Read more

Upside Robotics secures new funding to accelerate the future of sustainable farming

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.