ION light rail, we choo-choo-choose you!

Waterloo’s expertise in mobility technology is helping transform the community

Waterloo’s expertise in mobility technology is helping transform the community

By Sam Toman University RelationsWhen Waterloo Region’s light rail transit system officially begins moving passengers through Kitchener and Waterloo it officially becomes the smallest municipality in North America with such a system. University of Waterloo alumni, researchers and students all played an important role in making the ambitious project a success.

The rapid transit network known as ION stretches along a 19-kilometre path from Conestoga Mall in Waterloo, through the University of Waterloo campus, and down to Fairview Park in Kitchener. With 19 stops, the route connects cities, neighbourhoods and services across Kitchener and Waterloo. It also connects the Waterloo main campus with Velocity entrepreneurship program and the School of Pharmacy. Plans are already in the works to expand the train to Cambridge.

When the region first considered a light rail system to move its growing population and stimulate more sustainable urban densification, it didn’t have to go far to find talented transit experts who could help make the project a reality.

The University of Waterloo is emerging as Canada’s leader in mobility technology. It’s the first school in Canada to pilot Lime e-scooters, and construction is now underway on a $4.5 million research facility for autonomous vehicles. Plus, its top-rated School of Planning offers a deep pool of local talent with the interdisciplinary skill to get the project done right on a technical and social level.

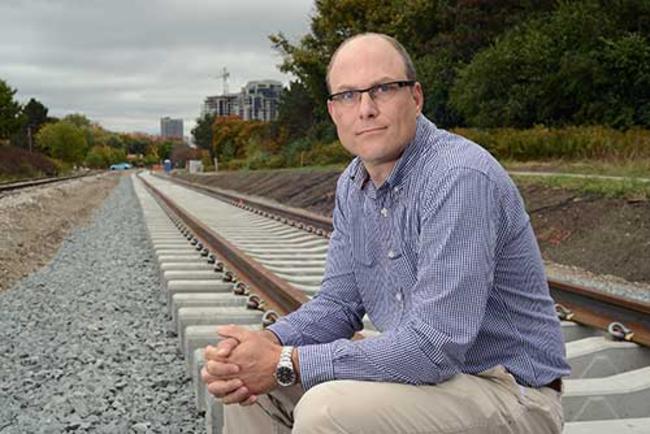

Jeff Casello — jointly appointed to the School of Planning and the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering — is regarded as one of Canada’s foremost experts in public transportation.

Jeff Casello — jointly appointed to the School of Planning and the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering — is regarded as one of Canada’s foremost experts in public transportation.

Since arriving in the area in 2004, he’s been a constant presence informing the region’s light rail project and its accompanying innovative urban development strategy.

“I think the Region of Waterloo is one of the first places in North America to actually put the transportation infrastructure in first, and try and use that to influence the land use, so we don’t continue to grow outward,” says Casello.

Local LRT skeptics weren’t convinced it could change the area for the better. But due to a two-year delay, the ION will be gliding through a region where it’s promise has already been revealed.

The $800-plus million-dollar investment in rail led to an urban transformation rarely seen before in Canada for a city this size. Seemingly overnight condo towers began springing up along the train route. On the day of the ION’s official launch, the Region of Waterloo is the second fastest growing community in Canada, fuelled by more than $2-billion in investment in its core.

“When you have a rail system like this, you have a different perception of the city; it seemed to be urban and vibrant and attractive to the creative class,” Casello says. “We see that we are able to attract firms like Google. With those kinds of companies coming in, this is basically the tax base for the region. You have this talent gain instead of a talent drain. Laurier, Conestoga College and Waterloo students who normally would be going to Toronto can stay local. Plus, we can attract Stanford or MIT or Cambridge students coming here who are looking for the kind of vibrancy and opportunities we have.”

The University’s impact on the Region of Waterloo extends far beyond simply getting the project done effectively. Managing its impact on a rapidly transforming community also requires continuous attention — especially in regards to social and economic disruption.

Margaret Ellis-Young is currently completing her PhD in Planning with the Faculty of Environment, under the supervision of professor Brian Doucet. Together they’re looking at how the ION, densification and urban development are influencing housing affordability.

Margaret Ellis-Young is currently completing her PhD in Planning with the Faculty of Environment, under the supervision of professor Brian Doucet. Together they’re looking at how the ION, densification and urban development are influencing housing affordability.

“Housing affordability is a concern that has consistently come up in my interviews with residents in LRT-adjacent neighbourhoods,” says Ellis-Young. “The LRT increases the attractiveness of nearby neighbourhoods for investors, developers and prospective residents, which translates into higher housing costs and the displacement of lower-income residents.”

In her research she has focused on residents' experiences, interviewing 65 residents (owners and renters) living in neighbourhoods along the LRT corridor.

“Much of what is being developed along the ION corridor is aimed at relatively affluent singles and couples, and many existing rental units are being renovated and rented out at higher rates,” she says. “Without concrete steps to protect and increase affordable housing along the LRT line, it is likely that many residents who rely on transit will not have easy access to the LRT.”

In a recent column in the Waterloo Region Record, Doucet laid out how the community can use the development associated with the ION to create more affordable housing.

“For a start, we need to ensure that we replace the demolished affordable units with a similar number in new projects,” says Doucet, who goes on to suggest that to actually increase the supply of affordable housing, we need to think bigger. We can do this by leveraging one of the key assets that all residents of Kitchener and Waterloo collectively own; surface parking lots… we own huge amounts of land that today is used to park cars. Tomorrow, these could be the sites for genuinely affordable housing that could transform the LRT corridor.”

At the end of the day, the ION is more than a research opportunity or development tool. It’s for getting people around town and is poised to open up new areas for students to experience and connect with the community they live in — students like Ellis-Young.

“Yes, I’ll definitely use it,” she says. “I plan on riding it to campus most days!”

Read more

When looking for a campus with the right stuff to trial its scooters, Lime saw Waterloo’s courage and commitment to embrace new technology as irresistible

Read more

Building an artificial brain that will one day replace human drivers is an incredibly complex technical challenge, say the researchers leading Waterloo’s autonomous vehicle project

Read more

Waterloo named home for Sustainable Development Solutions Network Canada, in partnership with WGSI.

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.