Computational models reveal effects of pregnancy on kidneys

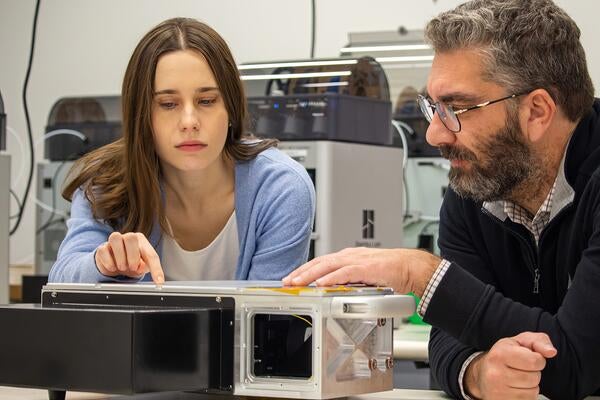

The computational models will help medical practitioners better understand the physiology of the kidneys during pregnancy

The computational models will help medical practitioners better understand the physiology of the kidneys during pregnancy

By Media RelationsResearchers are using computer simulations to better understand the impacts pregnancy can have on kidneys.

The new research will help medical practitioners better understand the physiology of the kidneys during pregnancy and develop appropriate patient care and treatments to improve health outcomes.

The researchers are interested in how the kidneys change during a typical pregnancy and how increased strain on the kidneys can lead to gestational diseases. The kidneys can also be affected by preeclampsia - unusually high blood pressure during pregnancy that may lead to organ damage.

“One thing that happens during pregnancy is that plasma volume expands to supply a developing fetus and placenta,” said Melissa Stadt, a master’s researcher in applied mathematics at the University of Waterloo. “There’s also retention of extra sodium and potassium, which are essential electrolytes during pregnancy. Basically, everything about pregnancy means a lot more work for the kidneys.”

The research team used computational models representing kidney function during mid-and late pregnancy. These in-silico experiments, so-called because they are essentially conducted in the silicon of computer chips, provide a way to simulate different kinds of strain on the kidneys that would otherwise not be possible to test in live pregnancies without substantial risk.

Because of the risks associated with human pregnancies, medical researchers often use other mammals like rats for research. Although computational models do not require any live test subjects, the research team still modelled rat pregnancies so they could incorporate more of the existing scientific data into their study.

“What’s powerful about computational modelling is that we can do trials that we could never do in live experiments,” said Anita Layton, professor of applied mathematics and Canada 150 Research Chair in mathematical biology and medicine at the University of Waterloo. “We can easily change one parameter and see the implications. Once we have the working model, we can see how these changes affect pregnancy.”

While computational models of organs like the kidneys are only ever approximations of what may happen in a specific individual case, they are a safe, cost-effective and timely way to conduct trials, not just of the various impacts pregnancy may have on the kidneys, but also of potential treatments and medications.

“If things go wrong in pregnancy, it can affect the mother for the rest of their life, and the growing fetus is very sensitive to any complications that affect the mother’s organs,” said Layton. “That’s where our models come in. Unfortunately, there’s a big gap in medical research related to all the changes in the kidneys of pregnant women. So our research is trying to make some progress and help improve health outcomes during pregnancy.”

Stadt and Layton’s new paper, “Adaptive changes in single-nephron GFR, tubular morphology, and transport in a pregnant rat nephron: modelling and analysis,” is being published by the American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology.

A car’s exhaust pipe emits black carbon. This sooty form of pollution alters the “light environment” beneath the snow, affecting plant growth. (Kmatija/Getty Images)

Read more

Research into light and snow interactions provides new insights into how pollution can affect vegetation growth and impact ecosystems

Read more

Researchers developed a process to reduce the amount of energy needed to run data centres

Read more

Phantom Photonics’ quantum remote sensing technology offers precision for industries operating in extreme environments

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.