More than basic shelter

Grad student’s winning paper illustrates the paradoxes of Somali nomadism and the desire for a temporary hut to be a home

Grad student’s winning paper illustrates the paradoxes of Somali nomadism and the desire for a temporary hut to be a home

By Carol Truemner Faculty of EngineeringThe torn, colourful fabric sheets of Somali huts deeply moved Amal Dirie when she visited her mother’s homeland last year.

The School of Architecture master’s student was so emotionally taken by the nomadic dwellings that she featured them in an award-winning essay titled The Idea of Home and Belonging.

Dirie’s illustrated piece won a Certificate of High Merit in the 2019 Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC) International Prize Scholarship competition.

Amal Dirie

“The poetics of discarded materials, an amalgamation of found objects that created the collage-like nature of the exterior was simply profound,” Dirie describes in her essay for which she will be formally recognized at the RAIC’s International Prize Gala taking place in Toronto next month.

Dirie, a 2017 alumnus of Waterloo’s undergraduate architecture program, says it took a number of years to save up enough money to travel to the country where her mother was raised and “her heart and mind remain.”

Before her trip to Somalia last summer, Canadian-born Dirie says she had never really explored her African roots.

“I was very curious to know about this country I’d never been to,” she says. “I had no concept of it. I would just tell people that’s my background, but I don’t know much about it.”

It was the nomadic huts and dwellings that first captured her attention when she arrived. Despite being built by internally displaced people within the city out of anything including scraps of fabric, plastic sheets, tree saplings and scavenged wood, each has its own unique sense of beauty from decorative hand-woven mats to fabric exteriors produced to provide natural ventilation.

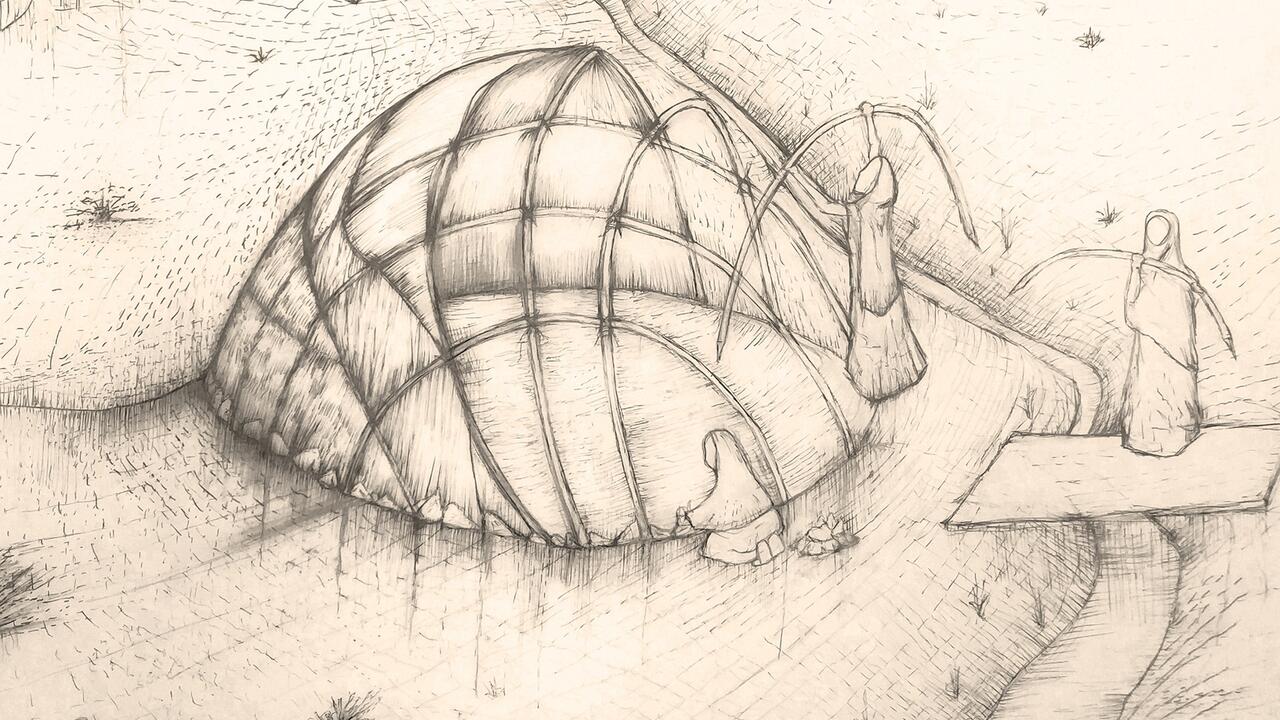

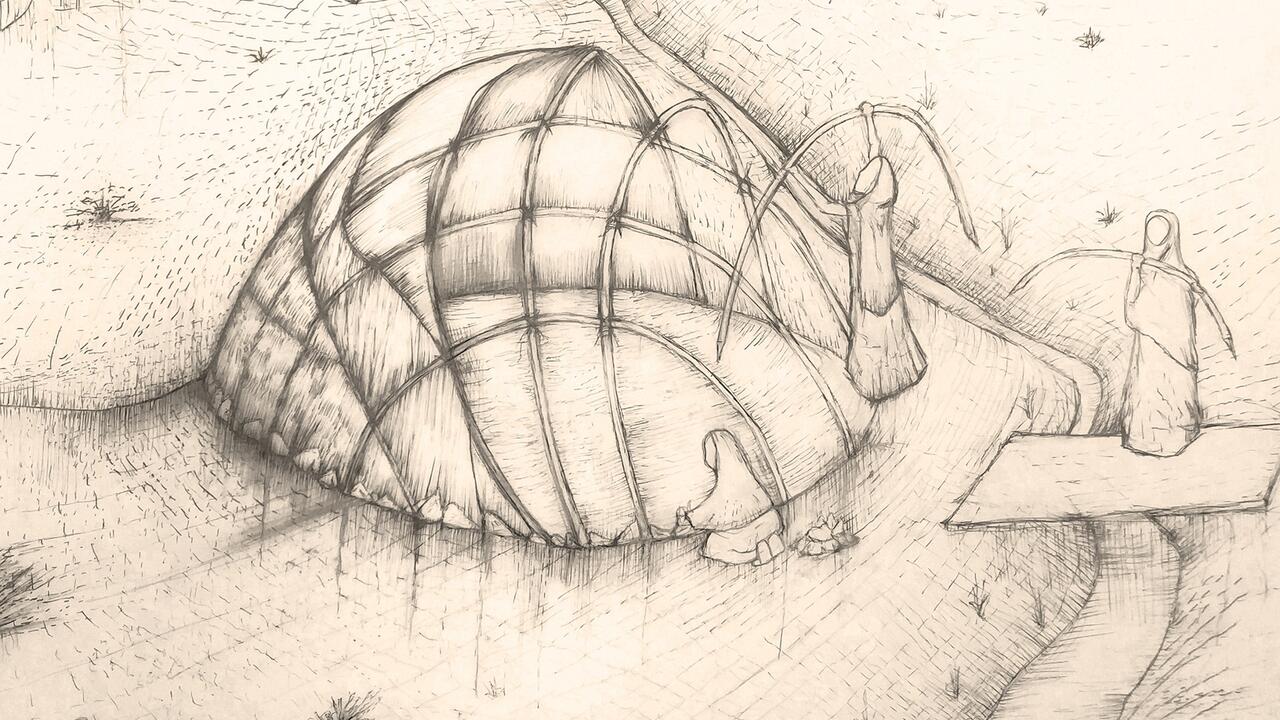

Amal Dirie’s award-winning essay includes illustrations depicting the idea of home and belonging in Somalia.

What Dirie found intriguing is that the huts are both designed and built solely by women.

“From the initial phase of setting up the armature to adorning the facade, the entire process illustrated the genuine strength and close-knit ties between the tribal women and ultimately provided them with the ability to withstand the toughest adversities,” Dirie says.

She also learned about the importance of the seasons and weather, which directly ties into the nomadic nature of the huts and their owners. Whenever there is a drought, the owners shift locations and the same happens when it rains heavily.

Dirie returned to Somalia for a second visit this summer to expand on what she discovered during her previous trip for her master’s thesis.

One of the things she focused her attention on during her six-week stay was the various creative techniques used to design and construct the huts such as singing different songs and reciting different poems according to what part of the dwelling is being completed at the time.

“The older generation knows the songs by heart, but they’re getting lost over time with the younger generation,” says Dirie.

Dirie, who plans to finish her master’s work by the end of this year, says she’s considering focusing her future career on humanitarian work.

“I’d love to work in Africa if I could,” she says. “I’m really passionate about designing for people who don’t have much — designing for need as opposed to luxury.”

Although she has nothing but praise for Waterloo’s architecture undergraduate and graduate programs, especially the flexibility of the courses to meet students’ interests, Dirie says she was struggling with the idea of practising architecture before going to Somalia last year.

The trip not only provided clarity with her educational path, it also helped with her response to this year’s RAIC essay competition that asked Canadian students to describe the moment they decided to become an architect or knew their decision to become an architect was the right one.

“The pivotal nature of the hut allowed me to leave the country with great assurance,” Dirie says in the last paragraph of her essay. “Knowing that its sentiments will forever influence the nature of my work as a developing architect, gaining a greater affinity of who I am and validating my pursuit of belonging.”

Read more

Recent alumni take their project to a prestigious business incubator in Henry the VIII’s former home

Read more

Waterloo students’ capstone design project nationally recognized for overcoming accessibility barriers

Read more

Engineering researchers combine biochemistry and smartphone AI software in new system

Read

Engineering stories

Visit

Waterloo Engineering home

Contact

Waterloo Engineering

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.