Revealing the long-lost secrets of HMS Erebus shipwreck

2G Robotics specializes in underwater laser scanners a hundred times more powerful than video or sonar imaging systems

2G Robotics specializes in underwater laser scanners a hundred times more powerful than video or sonar imaging systems

By Julie Stauffer Faculty of EngineeringFor more than 160 years, the HMS Erebus has been quietly lying on the Arctic Ocean floor roughly 1,500 kilometres northwest of Iqaluit. The wreck marks the end of Sir John Franklin’s tragic attempt to find a passageway linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans — an attempt that saw all 128 crew members perish when the Erebus and her sister ship the HMS Terror became trapped in Arctic ice.

In 2014, a team of Parks Canada archaeologists dominated headlines on both sides of the Atlantic when they located the long-lost vessel just off King William Island. And this summer, when they return north for a detailed assessment of their historic find, they’ll be packing made-in-Waterloo laser technology from 2G Robotics along with their laptops and scuba gear.

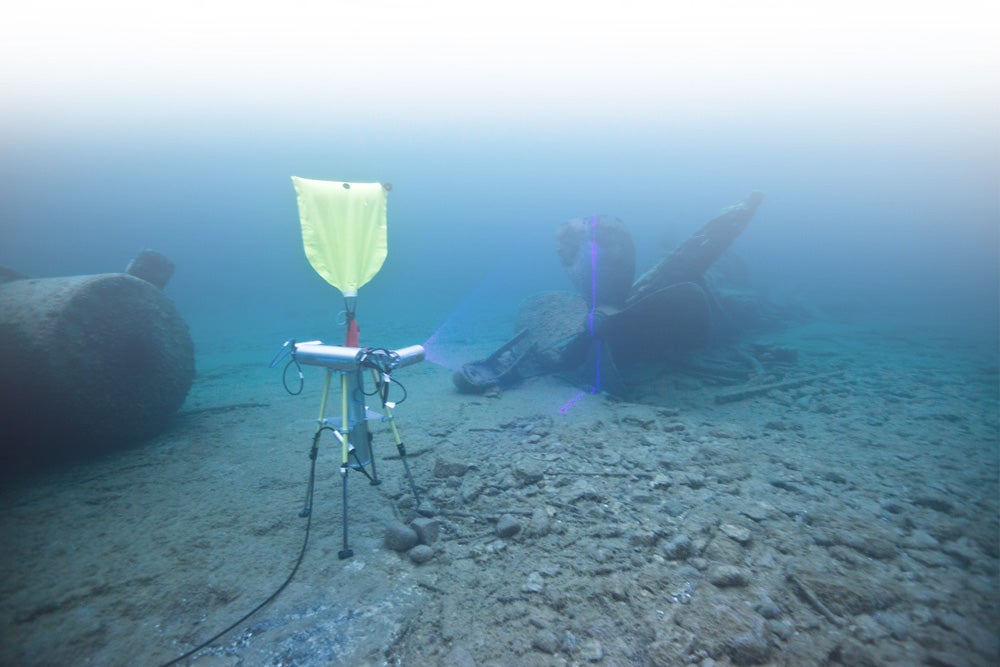

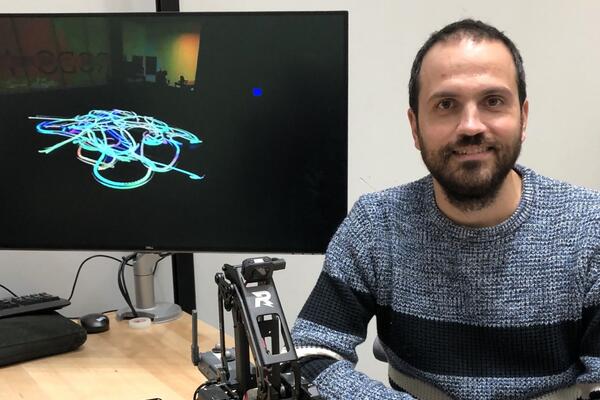

2G Robotics, founded in 2007 by University of Waterloo engineering alumnus Jason Gillham, specializes in underwater laser scanners a hundred times more powerful than video or sonar imaging systems. Essentially, they work by projecting a laser beam onto the target surface and analyzing how it gets reflected back. Apply a little trigonometry and you’ve got a digital 3D model of your object.

The company’s heftier ULS 500 scanner should provide astonishingly precise images of the Erebus’s exterior. “We expect to get some fantastic data of the overall structure of the ship,” says Gillham.

Meanwhile, divers can take the smaller hand-held ULS 200 right inside the vessel. The resulting 3D model will allow viewers around the world to venture below decks — inside the cabins, pantries, corridors and sleeping quarters — and see all the relics they contain. With a little luck, these clues may allow researchers to piece together the final days of the ill-fated expedition.

Gillham developed his laser scanning technology as a master’s student at Waterloo, merging his passion for marine exploration with his undergraduate degree in mechanical engineering. But it was the entrepreneurship support he found within the university and the broader Waterloo community that helped turn his technology into products now used around the globe. “It was the catalyst that allowed me to create the company,” he says.

Today, 2G Robotics boasts 14 employees and is growing fast. Over the past 12 months, the company has doubled in size. Meanwhile, its technology is transforming much more than marine archaeology.

Scanners from 2G Robotics have provided the images necessary to raise the capsized Costa Concordia off the Italian shoreline and have mapped ice caves in Antarctica Additionally, they’ve examined oil and gas pipelines three kilometres below sea level in the Gulf of Mexico, making the company’s technology the new standard for subsea pipeline inspections. “We’re doing stuff that nobody else has ever done before,” says Gillham.

In 2014, the company opened an office in Aberdeen, Scotland to better serve the North Sea oil and gas industry, but Gillham doesn’t plan to stop there. Over the next two years, he says, one of his main objectives is to boost 2G’s presence around the world. Adding the discovery of the HMS Erebus to his corporate CV certainly won’t hurt.

Read more

Robots the size of a soccer ball create new visual art by trailing light that represents the “emotional essence” of music

Read more

Waterloo prof leads a team of researchers to improve water quality through a community-focused approach underpinned by technical excellence

Read more

New medical device removes the guesswork from concussion screening in contact sports using only saliva

Read

Engineering stories

Visit

Waterloo Engineering home

Contact

Waterloo Engineering

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.