Can we fix COVID-19 and climate change in one breath?

Urban engineering chair argues we have a golden opportunity to do it right, with a concerted effort, when we do go back to a new normal

Urban engineering chair argues we have a golden opportunity to do it right, with a concerted effort, when we do go back to a new normal

By Nadine Ibrahim Turkstra Chair in Urban EngineeringWe are now trained to believe that being smart is to stay home, being socially connected is better online, and going to school is no more than rolling to the other side of the bed and turning on your computer, pyjamas optional.

Smart is being redefined as we adapt to survive current circumstances. We didn’t sign up for this, but we pivoted and changed habits and lifestyles for our own survival. Smart infrastructure is also being redefined, or rather rediscovered. While we debated what makes infrastructure smart, and what smart actually meant, the reality today demonstrates a plausible answer. Smart is the ability to have our services that run to our homes — including water, electricity, and natural gas — be delivered without the full labour force; and to have machines work where humans cannot, and equipment serve a dual purpose when necessary.

Nadine Ibrahim holds the Turkstra Chair in Urban Engineering.

Sustainability in cities is not that we do not use our cars despite gas prices being as low as 90 cents per litre, but that gas prices are low because the demand for our cars is not there, and in an ideal future sense, society has moved to other modes of transportation and reduced the need for commuting. Sustainability in cities is evident in much improved air quality that has made mountain peaks more visible, and city skylines more prominent, because urbanization is not triggering the burning of fossil fuels to move us around and deliver all our human needs.

It’s ironic that the economy is failing because we’re only buying what we need, and only essential services are operational. So, sustainability that meant we only consumed what we absolutely needed, and only bought what we needed for sustenance has hurt our economy. And in the news, we’re seeing the tragedy brought on by the coronavirus and positive news for greenhouse gas emissions curves. So, is this what sustainability looks like? No, far from it.

Sustainability is having the prosperity we desire in a thriving economy, and the beautiful images of clear unpolluted skies. Historically, our past behaviours have showed us that we can’t have both, but we also have proof that history is no longer a guide for the future. The economic growth curve can continue to go up, while the resource consumption and emission curve can take a dip. That’s city-level “decoupling,” which was coined by the United Nations Environment Program’s International Resource Panel in attempt to reimagine urban resource flows and the governance of infrastructure transitions. Decoupling refers to economic growth that is not tied to corresponding increases in natural resource use and environmental pressures.

We have a golden opportunity to do it right when we do go back to a new normal, but that won’t happen without putting in the effort to make these changes now. It’s the proverbial necessity being the mother of invention. We know that our previous normal wasn’t sustainable, but we haven’t been trained to see or know what these alternatives are, like alternative transportation modes, energy conservation and demand management, water saving strategies, and waste reduction and diversion. It’s an opportunity to rethink our travel choices, trade options, lifestyles, and consumer behaviours. What we really wanted was mobility (not the car), faster commutes (not the 100 km/h speed limit on highways), liveable homes, affordable housing, clean energy, and overall inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable cities.

Some cities have 2020 climate targets that will likely be met, and they have sustainable infrastructure to help them get there. But cities’ infrastructure and the status quo won’t be enough — not even close — to get them to their 2030 or 2050 targets. We are living in the “decade of action,” which should have started much sooner, prompted by COVID-19.

While we all turn into experts at reading exponential growth curves as we monitor COVID-19 cases, and while our brains are now attuned to the numbers, the “hockey stick” curve of climate change showing unprecedented global temperature rise is one we ought to be monitoring, and we should be bringing that curve down and flattening it, too.

*****

Nadine Ibrahim is a lecturer in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of Waterloo, where she holds the Turkstra Chair in Urban Engineering. This column was first published in The Hill Times and is reposted here with permission.

Read more

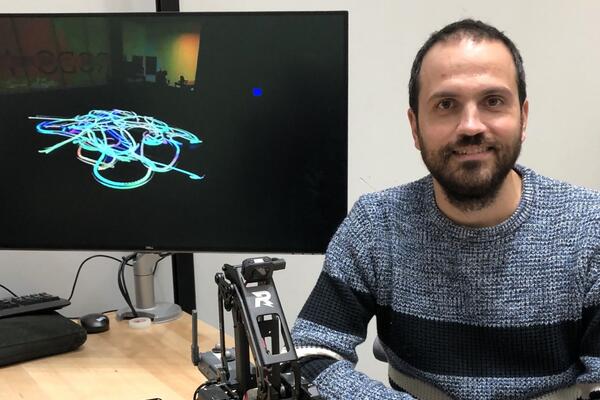

Robots the size of a soccer ball create new visual art by trailing light that represents the “emotional essence” of music

Read more

Waterloo prof leads a team of researchers to improve water quality through a community-focused approach underpinned by technical excellence

Read more

New medical device removes the guesswork from concussion screening in contact sports using only saliva

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.