Managing the pandemic through contact tracing apps

Technological innovation or a challenge to privacy and civil liberties

Technological innovation or a challenge to privacy and civil liberties

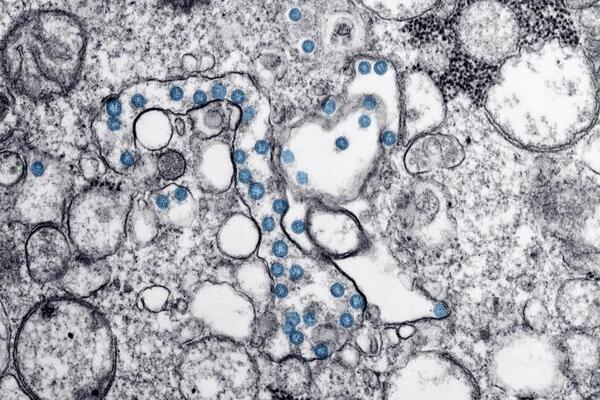

By Angelica Sanchez University RelationsIn an effort to track the spread of COVID-19, more and more contact tracing apps will continue to emerge. However, there are major concerns surrounding privacy issues when it comes to technology such as these apps collecting personal data.

During the lunch and learn virtual session, co-hosted by the Cybersecurity and Privacy Institute’s (CPI) and the Defense and Security Foresight Group (DSFG), CPI members discussed the potential challenges and concerns of COVID-19 contact tracing apps. The lunch and learn was moderated by University of Waterloo’s Florian Kerschbaum.

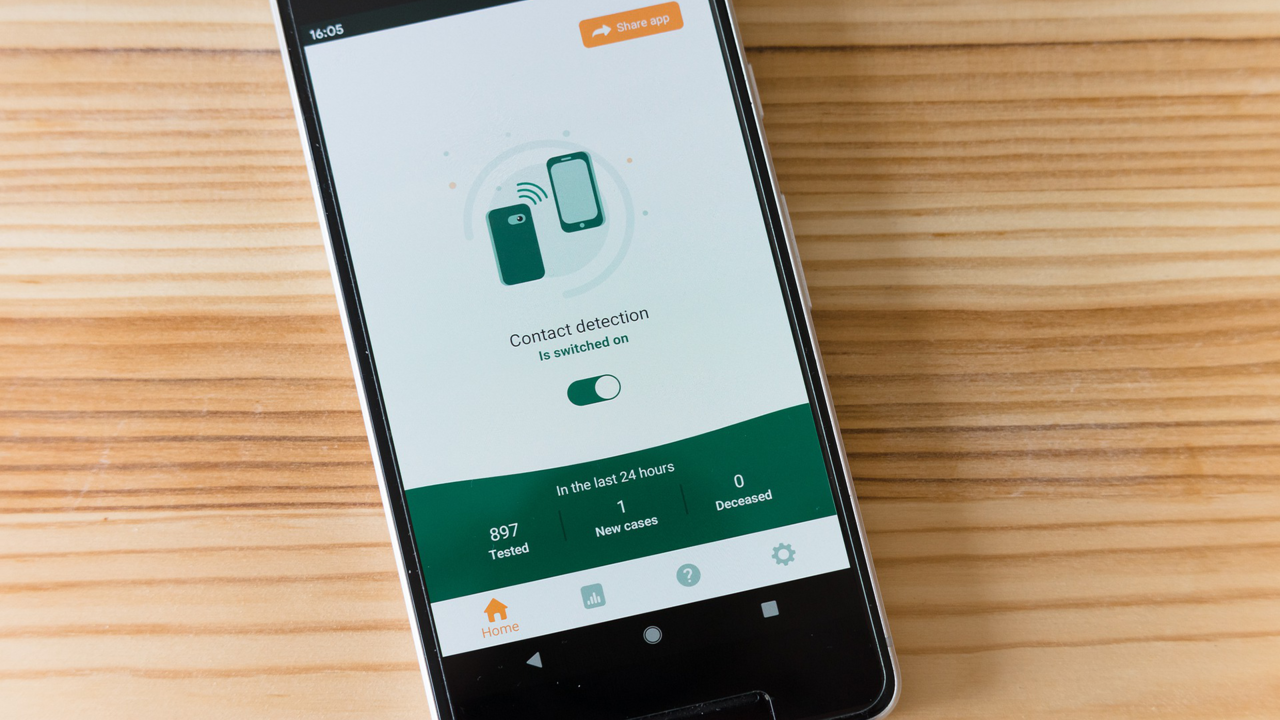

Douglas Stebila, a professor of cryptography in the Department of Combinatorics and Optimization, believes there are three issues — effectiveness, privacy and transparency — that developers should consider when designing a contact tracing app.

“In Canada, the system we’re looking at right now — between the provincial and federal government — is focused primarily on exposure notification. This aims to answer the question, ‘have I been near someone who tested positive?’ and giving that answer directly to me.” Stebila says. “We want to assess whether this app will be effective in that goal.”

Plinio Morita, a public health professor and the director of the Ubiquitous Health Technology Lab (UbiLab), agrees with Stebila that an exposure notification app would be very effective because it would tell people when they’re at risk. The problem with the system, Morita went on, is that people are really bad at following guidelines and regulations even though those individuals have been notified of being in contact with someone who has been diagnosed with COVID-19.

“I think what we’re going to see around the world are these pockets of cities that are downloading the app a lot and then showing success,” Morita says. “So that as we go along and evolve in the pandemic, other cities and communities will start to learn from that positive impact of the app has caused and consequently start downloading it more often.”

Bessma Momani, a political science professor, head of the DSF group and interim assistant vice-president of International Relations at the University of Waterloo, believes it would be extremely difficult for an app to achieve a high adoption rate if the app remains voluntary. Momani says, “What worries me is that eventually it’s going to be a slippery slope toward mandating people to do it.”

Momani continues to express her concerns with the privacy issues of these contact tracing apps where data collection would be involved. In other countries, this kind of digital surveillance has become a really important part of population control.

“I am worried about this becoming a convenient tool for policing and for all aspects of surveillance and monitoring public safety. I don’t think this is something I want any government to have a role in because we know power corrupts,” Momani says, “All forms of surveillance doesn’t end well for people’s civil liberties.”

Stebila discusses the two pieces of technology — Bluetooth and GPS tracking — that are being considered to be implemented for contact tracing apps. Stebila expresses no concerns about the Bluetooth feature because it requires no personal data collection and only records an individual’s physical contact history. In contrast, the GPS tracking feature would record the individual’s exact location, latitude and longitude, and upload that information into a centralized data base.

“It’s the centralized data collection of GPS information that really concern me,” Stebila says. “There’s a greater risk to privacy and gives governments so much more surveillance information.”

Morita hopes to see more evidence that these apps are really successful in proving the effectiveness of contact tracing and as well as curbing the pandemic. He adds that the public have the right to know about all the features provided by the contact tracing app and if it has any secondary uses. Society should be able to confirm that the app is only operating in the way of its intended purpose.

Read more

Preparing to reboot from the COVID-19 lockdown

Read more

Engineering professor wins federal funding to develop rapid, portable test for COVID-19

Woman in mask and gown

Read more

Engineering professor Bill Anderson part of major study on disinfection and reuse of PPE

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.