Floating houses that rise and fall with flood waters

Amphibious houses could protect First Nations and other vulnerable communities devastated by floods, says Waterloo architecture prof

Amphibious houses could protect First Nations and other vulnerable communities devastated by floods, says Waterloo architecture prof

By Suzanne Bowness Marketing and Strategic CommunicationsAmphibious houses that rise and fall with flood waters would help save lives and protect First Nations and other vulnerable communities devastated by flooding every spring, says a University of Waterloo architecture professor.

Elizabeth English says amphibious housing allows homeowners to evacuate with peace of mind, knowing that when they return, their houses will find little, if any, damage. Remaining during a flood is not recommended, except in emergency situations

Waterloo prof establishes Buoyant Foundation Project

The challenge for remote northern communities is that when the homes are flooded, there is nowhere for people to live while their houses are being rebuilt,” explains English.

Two thousand aboriginal people are still out of their homes three years after heavy flooding in Manitoba. English, who established the Buoyant Foundation Project, says amphibious housing would protect First Nations people from losing their homes and being displaced for long periods of time.

Two thousand aboriginal people are still out of their homes three years after heavy flooding in Manitoba. English, who established the Buoyant Foundation Project, says amphibious housing would protect First Nations people from losing their homes and being displaced for long periods of time.

At least one community has been declared uninhabitable in Manitoba and others are fractured by the loss of family and neighbors who are living far away in hotels and temporary housing in Winnipeg.

“The engineering is fairly simple, it’s the social and cultural aspects of this that make it compelling,” she adds. “The policy impediments also that make it complex.”

Learn more about the Buoyant Foundation Project (video).

Researcher witnessed devastation of Hurricane Katrina

English was researching the impacts of wind-borne debris at the Louisiana State University (LSU) Hurricane Centre when Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005. She began working on amphibious housing after she witnessed first-hand the needless loss of life and how entire neighborhoods were torn apart by flooding. “My social conscious became so overstimulated that I decided to start working on flood mitigation,” says English.

The concept involves attaching pontoons, or “buoyancy blocks”, beneath the house. They can be made of expanded polystyrene (EPS or “Styrofoam”), empty tanks or barrels, or other combinations of materials that can displace water. When flooding reaches the home it floats up guided by “vertical guidance posts” embedded in the ground next to the house.

House settles back down on original foundation

After the flood disappears, the house settles back down on its original foundation. “The whole thing happens passively so you don’t have to be there to do anything,” says English.

Unfortunately, in Louisiana, federal insurance and mortgage policy regulations are currently preventing the technology from being widely installed.

Yet English is optimistic that organizations like the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) recognize the need for progress and that a challenge case to create a precedent would likely pave the way for policy change. “Changes like this don’t happen overnight,” she says.

In the meantime, English is reaching out to other communities where the technology might prove helpful. While she’s looking at Canadian locations like Kashechewan First Nation in Northern Ontario and Peguis First Nation in Manitoba, she’s also connected with international regions including Nicaragua and Bangladesh.

She also sees opportunities in Haiti, Vietnam, Thailand and the Philippines. “There’s a lot of interest around the world,” says English. “My work now is more focused on vulnerable at-risk communities in developing countries.”

University of Waterloo researchers Olga Ibragimova (left) and Dr. Chrystopher Nehaniv found that symmetry is the key to composing great melodies. (Amanda Brown/University of Waterloo)

Read more

University of Waterloo researchers uncover the hidden mathematical equations in musical melodies

Read more

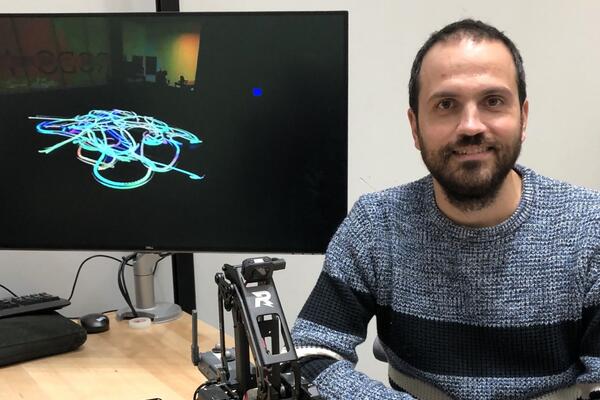

Robots the size of a soccer ball create new visual art by trailing light that represents the “emotional essence” of music

Read more

Waterloo prof leads a team of researchers to improve water quality through a community-focused approach underpinned by technical excellence

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.