What’s going on inside the minds of climate change skeptics?

Waterloo research team creates mapping tool that identifies emotional hotspots in disputes

Waterloo research team creates mapping tool that identifies emotional hotspots in disputes

By Heather Bean Marketing and Strategic CommunicationsScience has shown that humans are influencing climate change, but according to a recent poll almost half of Americans don’t believe we’re affecting the Earth’s climate.

Why do people and politicians cling so tightly to beliefs that don’t stand up to science and reason?

“It’s important to understand what’s happening to our climate, but we also have to look at what’s going on in people’s minds to understand why it continues to happen,” says Steven Mock, a research fellow at the Balsillie School of International Affairs (BSIA). “Emotional hotspots are key to understanding why people hold onto beliefs not supported by evidence.”

Steven Mock

Mock, along with a team of researchers based in Waterloo, recently published a paper called The Conceptual Structure of Social Disputes describing how a tool called Cognitive Affective Maps (CAMs) can be used to help resolve conflicts. CAMs look at the emotions behind our ideologies and beliefs.

The research team included Balsillie School Professor Thomas Homer-Dixon, and Killam Prize scholar Paul Thagard, who is also director of the University of Waterloo’s Cognitive Science program. Manjana Milkoreit, a Balsillie School doctoral graduate and Tobias Schröeder a recent Waterloo postdoctoral fellow were also part of the team.

Paul Thagard

The paper examines how CAMs can be used in four different disputes:

CAMs have potential as a tool for negotiators, because they help identify “what it is that people really are emotional about in a situation,” says Mock. “Our argument is that what goes on in people’s minds—the beliefs that are shared by communities and societies—are in their own ways complex systems.”

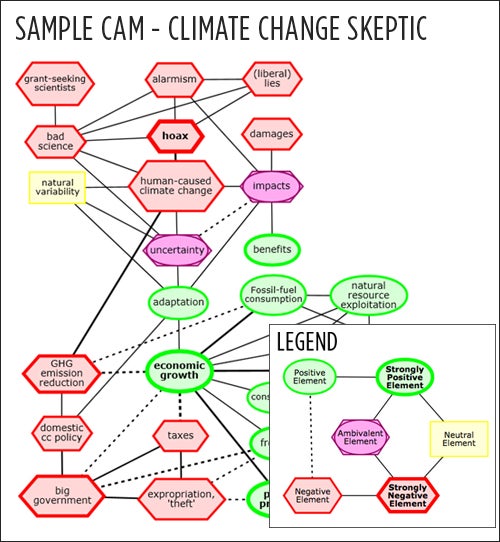

CAMs are visual representations of the way people feel about their ideas. Using networks of coloured shapes, CAMs portray related ideas and concepts in a belief system and the positive or negative valence or direction of emotion associated with various ideas.

Anyone can make a CAM: individuals can represent their own values, or negotiators can compare the CAMs of parties in conflict to find points of agreement or tension with a software program called Empathica.

The Waterloo team will host a workshop later this year with negotiation practitioners to find ways to further develop CAMs as a tool for dispute resolution.

A sample cognitive map depicting how different emotions and beliefs about climate change (such as uncertainty, benefits, and alarmism) are interconnected.

Read more

To meet our AI ambitions, we’ll need to lean upon Canada’s unique strengths

Read more

New research from the University of Waterloo centres Haudenosaunee-led efforts in the repatriation and reclamation of cultural and intellectual property

Read more

Researchers awarded funding to investigate ecology, climate change, repatriation, health and well-being through cultural and historical lens

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.