Redesigning with innovation in mind

How Waterloo is transforming its classrooms to develop future talent

How Waterloo is transforming its classrooms to develop future talent

By Natalie Quinlan University RelationsCOVID-19 has reshaped the way educators around the world teach and students learn. Fading are the days where rows of desks facing the front of the classroom are standard practice. Instead, reliance on heightened opportunities with technology integrated with flexible learning schedules and environments is paving the way for a revolution in education. The pandemic has, in many ways, forced changes in teaching and learning that will remain present even after it’s over.

This transition was already underway at Waterloo pre-pandemic. For several years now, the University of Waterloo’s approach to teaching and learning has also been shifting its focus. Based on research and expert advice, instructors are relying less on traditional lecture formats and focusing their attention on learning styles that encourage students to develop practical skills necessary for the working world.

These include learning opportunities stemming from teamwork, collaboration and navigating various forms of technology. Traditional lecture halls where rows of chairs face the front of the room are being redesigned with flexibility in mind, allowing furniture to move and environments to be easily modified for a more collaborative experience.

“It doesn’t mean we throw out everything that we’re doing,” David DeVidi, associate vice-president, academic at the University of Waterloo. “But some of what we do needs to change so that we can be offering students what they will need ten years from now.”

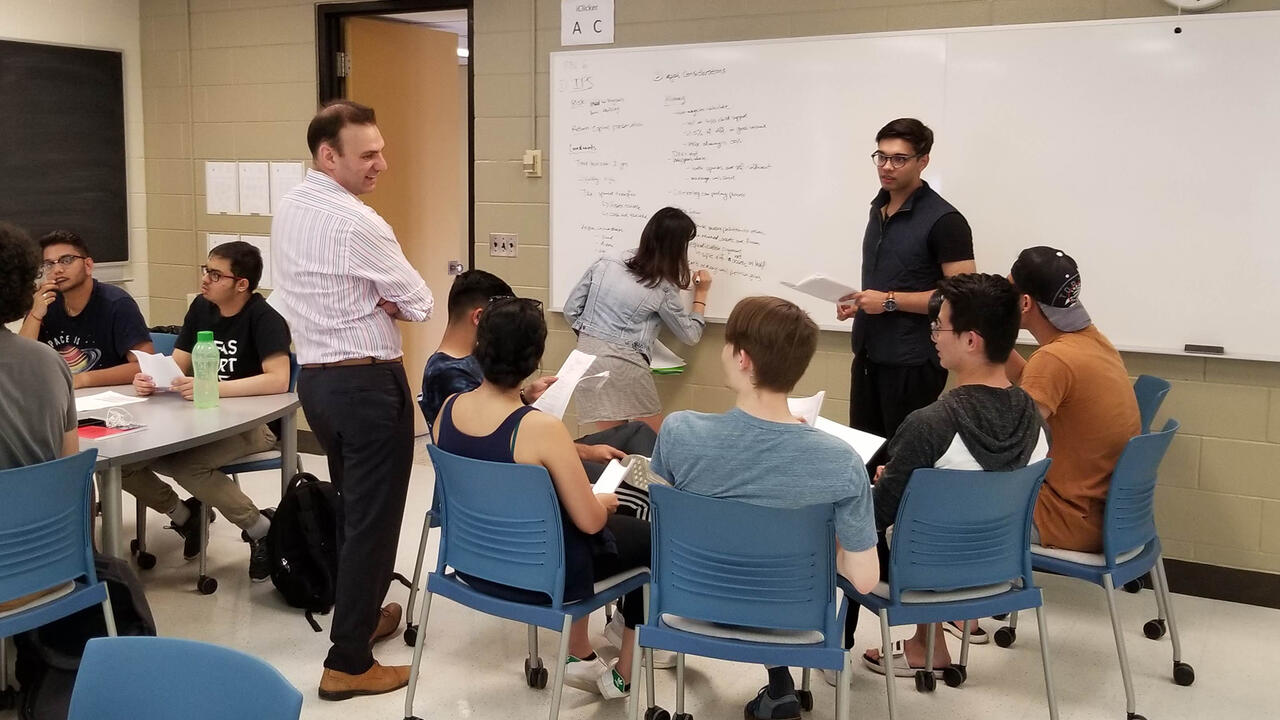

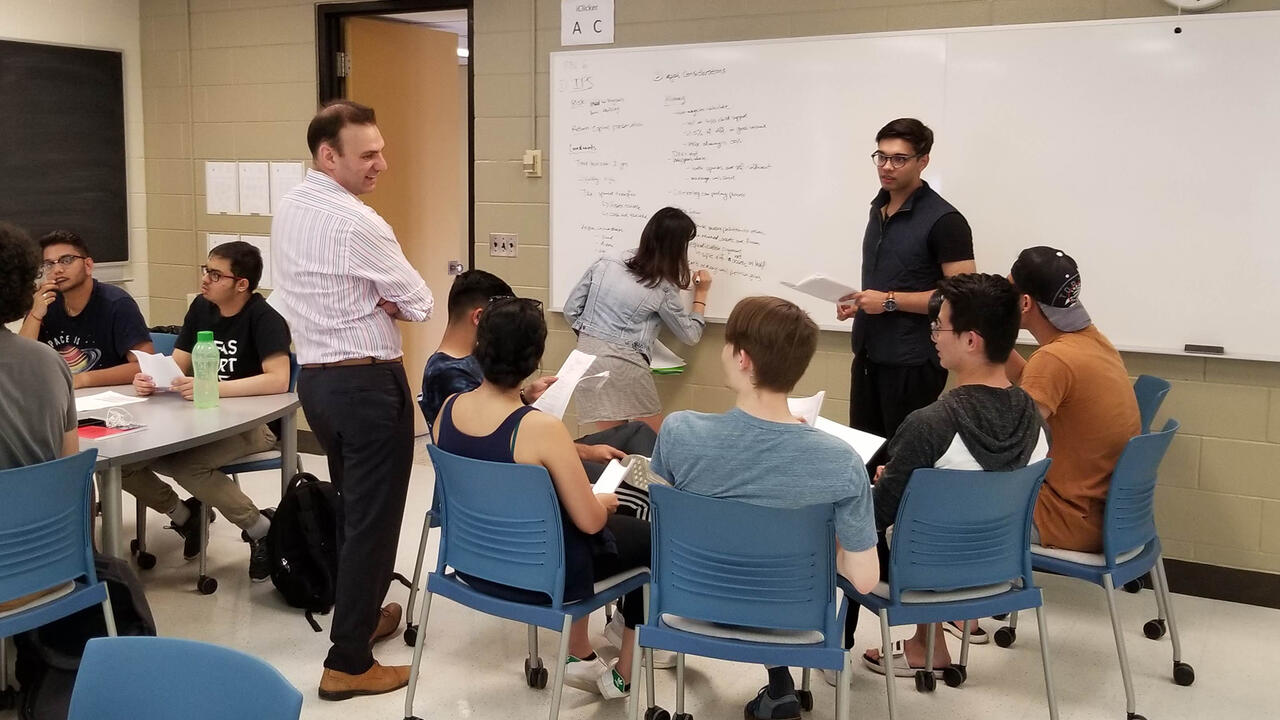

Flexible learning classroom versus traditional lecture hall. (Photos taken pre-pandemic)

The same momentum can be seen in the University’s strategic commitment to enhancing educational opportunities by creating increasingly flexible curricula that stimulate reflective, deep learning for experiences that can be applied to real-world settings.

Many of these newer approaches to pedagogy will work much better in less traditional learning spaces, and the University is working to gradually transform its stock of teaching spaces to make them more adaptable. Leading this initiative has been the Teaching and Learning Spaces Committee (TLS), established in 2020, which has received a multi-year financial commitment to upgrade and update some of Waterloo’s classrooms and other learning spaces.

David DeVidi

> Associate Vice-President, Academic

“Right now, most of our spaces have rows of chairs and desks that are nailed to the floor which is, of course, fine for traditional lecture courses, but if we’re hoping to continue doing innovative things, we’ll often need spaces that go beyond just lecture settings,” says DeVidi. “That’s the idea behind improving these classrooms — refreshing and redesigning them — this flexibility will present our instructors and students with more options for teaching and learning.”

University leaders approved approximately $1.6 million of additional funding for larger projects set for completion in 2023. One will be an active learning space that includes substantial learning technologies, such as multiple screens placed strategically around the room to facilitate idea-sharing in group settings, whether learners are in-person or remote. Upgrades to two larger classrooms in a mathematics building will also be taking place.

This ongoing project is only one of a group of related initiatives designed to support a culture of pedagogical excellence, creativity and innovation at Waterloo. Also on the horizon is the Teaching Innovation Incubator, a concept at the centre of the proposals brought forward during the development of Waterloo’s 2020 – 2025 strategic plan.

The University already has systems that support incremental improvement in teaching. The Centre for Teaching Excellence, for instance, can help an individual instructor become a better teacher or a program to decolonize its curriculum.

“The Incubator will be a place to try out ideas with the potential for more disruptive changes,” says DeVidi. “It will be a one-stop-shop: projects accepted into the incubator will get all the supports they need to develop, test drive and evaluate their potential for success. That will put everyone in a good position to decide whether the idea is worth investing in to scale up and implement.”

The concepts all aim at preparing the University and its students for the complex future that awaits them.

For more information on the Teaching and Learning Spaces initiatives at Waterloo, visit their website.

Read more

Work-Integrated Learning program helps students discover their talents and prepare for an ever-changing future

Read more

New program will offer one-term work projects, with mentorship support from industry partners

Read more

School of Pharmacy takes informatics online

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.