Putting together the puzzle on white-nose syndrome

Study highlights the biological mechanisms behind a disease that has caused over 90 per cent declines in some bat species

Study highlights the biological mechanisms behind a disease that has caused over 90 per cent declines in some bat species

By Katie McQuaid Faculty of ScienceMillions of bats in North America have died from white-nose syndrome, and a new study from the University of Waterloo explores why and how the fungal disease has devastated bat populations on this continent, while it has had little effect on bats in Europe.

White-nose Syndrome (WNS) is a fungal pathogen in bats caused by the psychrophilic fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans. Continuing to spread into other geographical areas, it disrupts bat hibernation, causing them to wake repeatedly during winter and die from starvation or dehydration. Instead of activating immune pathways to clear the fungal infection, the North American bats’ immune system response drives inflammation and tissue damage, without eliminating the fungus.

Bat species most affected by WNS are insectivorous and provide valuable natural pest control by consuming crop and forestry pests. In the U.S. agricultural sector alone, crop destruction and the need for chemical pesticides attributed to declining bat populations was estimated to be $26.9 billion between 2006 and 2017, amounting to $35 billion today when adjusted for inflation.

“Since the pathogen's detection in North America 20 years ago, likely brought here from Europe via human travel or trade, some species of bat have experienced population declines of more than 95 per cent,” said Dr. Brian Dixon, professor of biology at Waterloo. “European bats evolved alongside the fungus, and because of that, they don’t exhibit the same detrimental inflammatory response, and the effect on their bat population hasn't been as dramatic.”

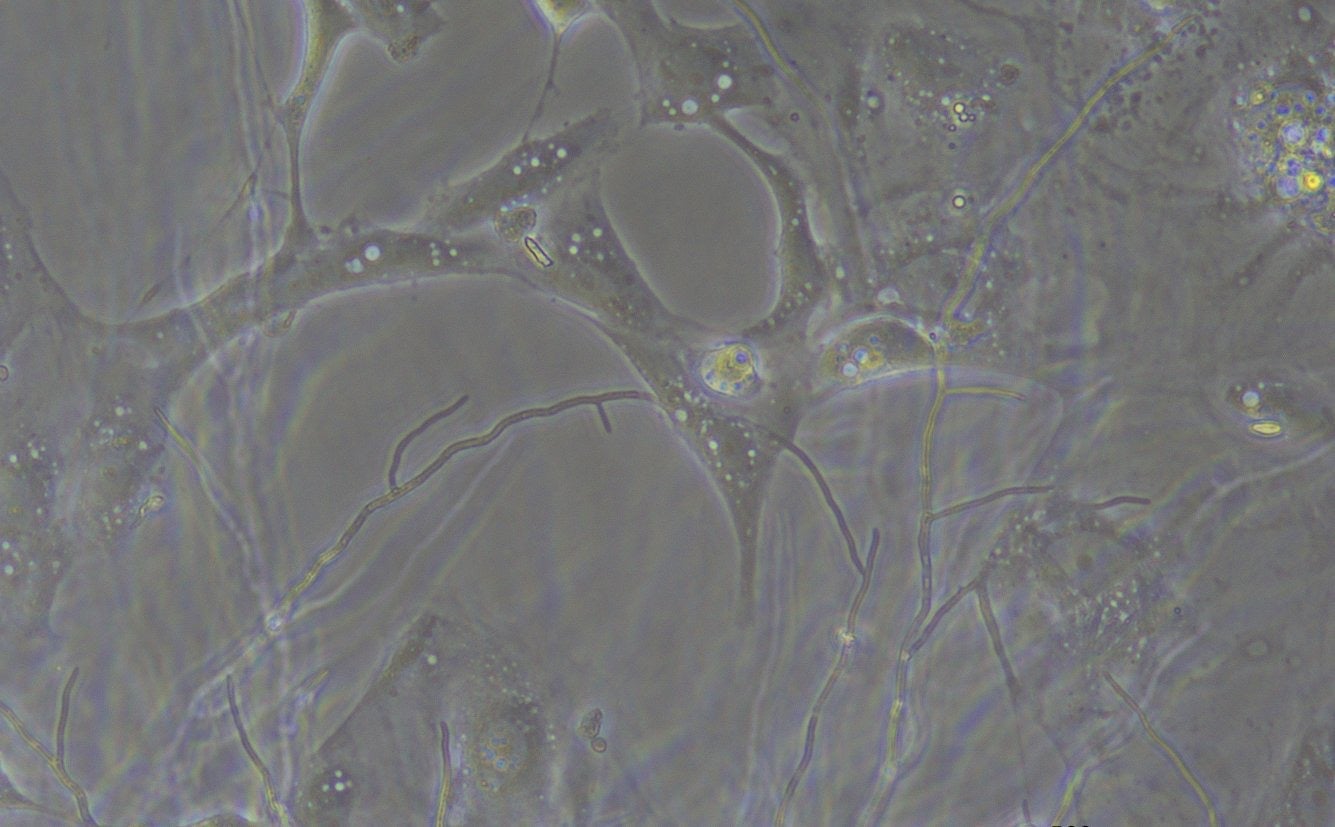

A rare glimpse of P. destructans hyphae invading bat cells - a first for this cell line and the first step toward developing an in vitro model of White-nose Syndrome infection.

Undergraduate student Maya Jacewicz worked with Dixon and Noah Rogozynski, a master’s student, to gather existing research to understand why bats are responding so negatively to WNS. They pulled from studies across multiple disciplines on everything from bat skin bacteria to vaccine trials, but with information so fragmented, they found major gaps in collective knowledge and understanding of what’s happening inside infected bats.

“Bringing this information together felt like assembling the pieces of a puzzle that may finally reveal the biological reasons behind the devastating impacts of this disease over the past two decades,” Jacewicz said. “We want to know why North American bats respond the way they do and what is happening inside them that triggers such a harmful response.”

Some experimental studies have shown that bats with stronger survival outcomes may activate a different, more protective immune pathway. This finding suggests that the type of immune response, not just its strength, matters for survival. This imbalance in immune responses between species may reflect an evolutionary trade-off that helps bats tolerate viruses but leaves them vulnerable to fungal diseases.

The researchers hope to conduct similar studies across multiple bat species to identify differences between North American and European bats and to understand why some Canadian species are better at fighting off the infection than others. By working with bat cells in culture, they will compare immune responses, decipher the genes that help clear the fungal infection, and distinguish other shared characteristics of the species that can fend off the infection.

“By combining insights from multiple scientific approaches, we might be able to develop more effective strategies to slow the spread of the disease and protect vulnerable bat populations,” Jacewicz said. “We hope that when our research is complete, our work will play a significant role in future management and conservation strategies.”

With WNS spreading across the country, and the threat of a second and equally disastrous strain of the fungus present in Europe, research into how and why it spreads and how we can help our bat population is more important than ever.

The paper, Strategies and limitations of the bat immune response to Pseudogymnoascus destructans: the causative agent of white-nose syndrome, appears in Frontiers in Immunology.

New research examines the carbon-removal potential of strategic planting (Getty Images/Zhao Qin).

Read more

AI-powered modelling shows planting in northern forests could help Canada become carbon neutral by mid-century

A member of the research team investigates a stream on the surface of the ice. (University of Waterloo)

Read more

Study reveals that airborne dust promotes algae growth that speeds glacial melt

Read more

Waterloo research is leading the fight against an invasive plant threatening Ontario wetlands

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.