Healthier societies begin with architecture and design

Looking beyond automation as an architect weighs in on COVID-19

Looking beyond automation as an architect weighs in on COVID-19

By Natalie Quinlan University RelationsThe outbreak of COVID-19 has forced the world to reconsider the way we live — right down to the structures that house us.

With more information surfacing on the transmission of the virus every day, professionals in architecture and design are re-imagining what a post-COVID society might look like.

It’s also prompting organizations to take a closer look at the layout of their quarters.

A new collaboration between the School of Architecture and Cambridge’s Self-Help Food Bank is one of these latest initiatives magnified by COVID-19.

To ensure the continued safe delivery of their services, the food bank is seeking guidance from the School of Architecture, pairing the non-profit organization with one of its master’s students.

“It means there’s someone who is taking the time to really analyze their situation,” Anne Bordeleau says, O’Donovan director and professor at Waterloo Architecture. “We’re looking at both short-term and long-term conditions — how they revisit distributing food, but also the appropriateness of the site’s location and how it can function more productively.”

It’s an initiative that, while in the very early stages, is at the front-and-centre for many businesses facing re-opening.

Anne Bordeleau, O’Donovan director and professor at Waterloo Architecture.

Anne Bordeleau, O’Donovan director and professor at Waterloo Architecture.

An interconnected world: moving fast and far

Combining former functionality and productivity processes with new cautionary measures, conversations surrounding increased automation and anti-bacterial surfaces within future design are taking centre-stage. But Bordeleau is encouraging society to look beyond these quick-fix solutions, noting that the sites our future architects will build on, the projects they’ll design, the materials they’ll specify and the people they will choose to serve will have social, environmental and economic repercussions.

“We need to change more broadly, how we live together and how we share this world. Healthier societies begin with architecture and design,” Bordeleau says. “The way in which we deal with health impacts how we approach our planning of the cites and where certain activities happen. This is not just about the materials or mechanical systems we use or how we plan waiting rooms in hospitals, but how we care for more vulnerable members of our community in the world we design for ourselves.”

It’s why, in her big-picture approach, Bordeleau is hoping professionals across all industries, not just architecture, look at the pandemic as a lens to respond to larger systemic issues (e.g., climate change, food security and vulnerable populations becoming even more vulnerable), and not as the single cause for solution. It’s also why the School of Architecture has been developing a new program in Integrated Design Arts and Technology, an education that could get future designers to think creatively and collaboratively across disciplines.

“This is an interconnected world — things move fast and far. More than ever, we have to be architects — working across scales, working across disciplines and working holistically,” Bordeleau says. “As we address COVID-19 or post COVID-19, we have to go back and work hard at these inequities, the social imbalances, the unsustainable rhythms of consumption and modes of productions. We have to rethink the way we build and think of our homes and cities, our relations to our immediate and less immediate, but no less connected environment.”

Read more

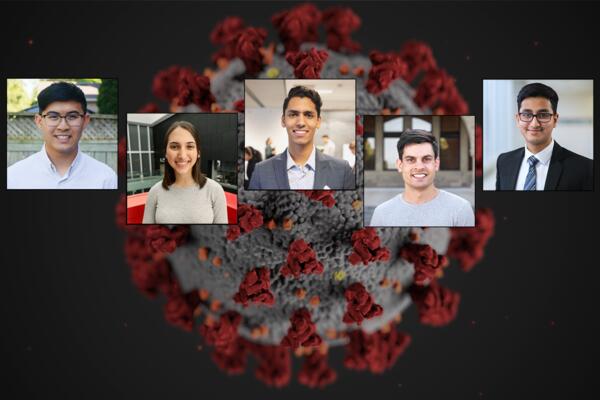

SeroTracker could inform strategies for reopening economies in Canada and around the world

Read more

New AI algorithms that provide information about physical distancing, the isolation measures that a person who tested positive for COVID has taken, and testing results for individuals will be incorporated into a contact tracing app to better forecast the spread of COVID-19 and predict any further outbreaks of the virus.

Read more

Production focus pivots to 3D-printed parts for face shields worn by health-care professionals

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.