Fast, affordable water testing for the developing world

Engineering researchers combine biochemistry and smartphone AI software in new system

Engineering researchers combine biochemistry and smartphone AI software in new system

By Brian Caldwell Faculty of Engineering

Sushanta Mitra

Sushanta Mitra was doing field trials in remote areas of India when he was struck by how many people with no reliable access to clean water were connected to the internet via smartphones.

The contrast amazed him. It also gave him a good idea.

Six years later, the University of Waterloo engineering professor and his colleagues are refining new technology that puts the power to monitor water quality in the palms of people in the developing world.

Woman collecting a water sample from a well.

“In remote locations, you’re talking about two days to take a sample, culture the bacteria and get results,” says Mitra, executive director of the Waterloo Institute for Nanotechnology. “That is a major problem because people will keep drinking the water and fall sick or even die.”

The new addition to their existing testing tools — which use paper strips, gel and plastic filters that change colour when E. coli bacteria are present in water — is AI trained to read and interpret the results.

Users simply take a smartphone photograph of the strip, gel or filter and the AI application determines, based on colour change, whether there is contamination or not. It has proven 99.99 per cent accurate, all but eliminating errors made by human interpreters.

Work is ongoing to refine the system through training with more data to also predict E. coli concentration, and therefore the level of contamination, by interpreting the intensity of the colour change.

Woman collecting a water sample from a pump during field tests.

“We brought two disciplines together,” says Mitra, a professor of mechanical and mechatronics engineering. “One is biochemistry and the other is a mathematical tool, a convolutional neural network.”

Tests using mobile water kits that were first developed by the researchers cost about $15 each. A subsequent, simpler system using paper strips costs about $1 a test. The AI app will be publicly available for free downloading.

Lab tests to determine the degree of contamination, by contrast, cost about $60 apiece, an enormous expense in developing countries that lack modern water infrastructure.

“This is a very empowering tool,” says Mitra, whose primary collaborator is post-doctoral fellow Naga Siva Kumar Gunda. “Even people who don’t have access to clean water have access to cellphone networks.”

In addition to countries such as India, the low-cost testing technology is attractive for use in remote or agricultural areas of the developed world, and for more frequent testing in modern municipal water treatment systems.

Naga Siva Kumar Gunda (far left) and Sushanta Mitra (fourth from right) with officials during their field trials in India.

The new AI app could also be adapted for other kinds of tests involving colour change. Possibilities include testing for heavy metals in water or diseases such as dengue fever and malaria.

“With this technology, we eliminate the need for independent lab tests,” says Mitra. “It saves time and costs as well. Our goal is to provide fast, accurate testing on a mobile platform as technology for the masses.”

Read more

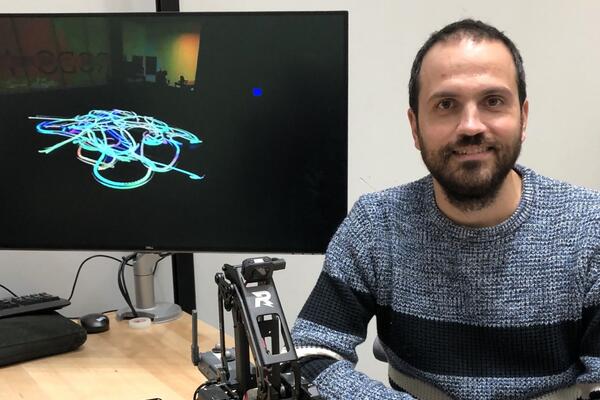

Robots the size of a soccer ball create new visual art by trailing light that represents the “emotional essence” of music

Read more

Waterloo prof leads a team of researchers to improve water quality through a community-focused approach underpinned by technical excellence

Read more

New medical device removes the guesswork from concussion screening in contact sports using only saliva

Read

Engineering stories

Visit

Waterloo Engineering home

Contact

Waterloo Engineering

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.