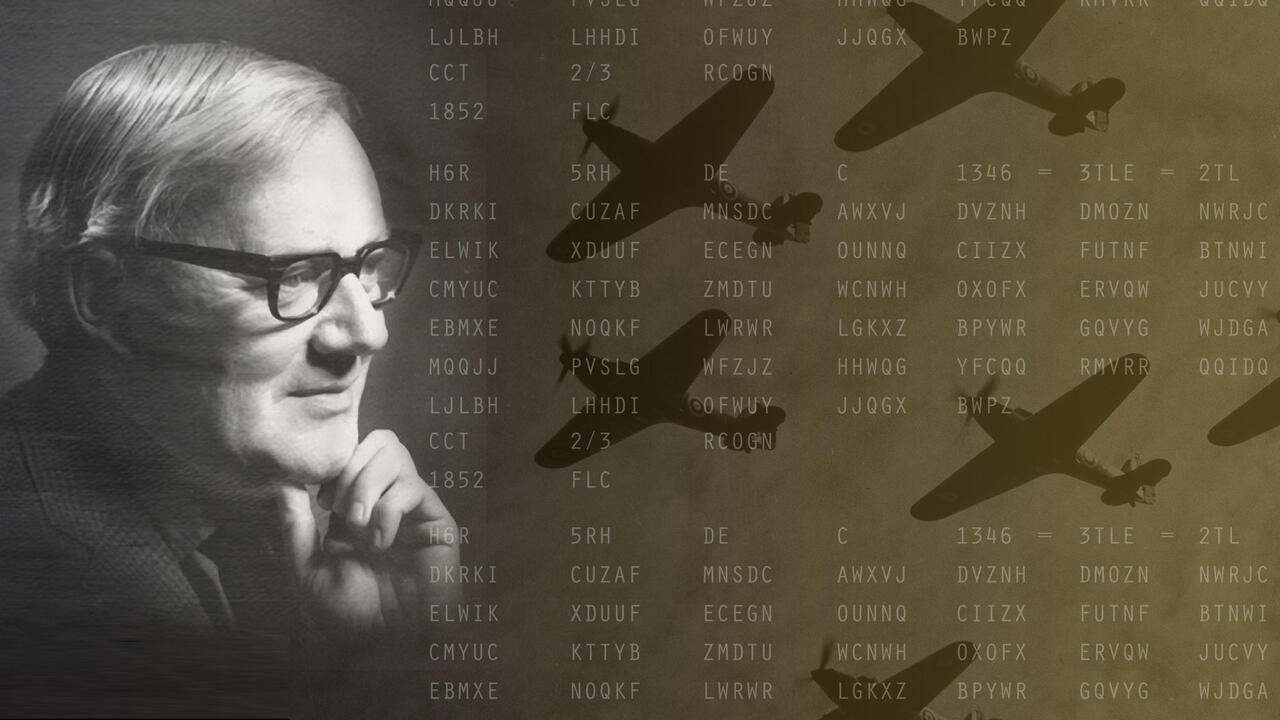

Keeping secrets

The humble math professor who cracked top Nazi code

The humble math professor who cracked top Nazi code

By Nancy Harper University of WaterlooOne of the most influential code breakers of the Second World War spent more than two decades quietly shaping the University of Waterloo’s fledgling Faculty of Mathematics into a global powerhouse.

As a professor of mathematics, William “Bill” Tutte was revered for his mathematical genius and pioneering ways, attracting top-level researchers and building the reputation of the University from the ground up.

And yet for the entire length of his decorated career at Waterloo, no one — not longtime friends, colleagues or students — knew Tutte had been one of the brilliant minds of Bletchley Park, site of the now-legendary team of wartime code breakers who worked feverishly to stop Hitler’s advance.

And while the history of Bletchley Park was dominated by Enigma and the tragic story of Alan Turing — recently immortalized in the Oscar-winning film The Imitation Game — historians and those who knew Tutte personally believe Tutte’s contributions were far greater.

It took almost 50 years for the truth about Tutte’s wartime role to be revealed. During that time, he emigrated to Canada, married Dorothea Mitchell, lived happily in the tiny hamlet of West Montrose and, with characteristic modesty, got on with the job of being a math professor.

"We should never forget how lucky we were to have men like Professor Tutte in our darkest hour and the extent to which their work not only helped protect Britain itself but [saved] countless lives."

DAVID CAMERON, British Prime Minister, in a 2012 letter to Tutte’s remaining family in Newmarket, England

Born into humble circumstances in Newmarket, England, in May 1917, Tutte received his early education at the village school in Cheveley. His potential was quickly recognized with a scholarship to the Cambridge and County Day School — which ultimately led to a scholarship to study chemistry at Trinity College, Cambridge.

At Cambridge, Tutte was able to nurture his passion for mathematical puzzles and in 1941 he received an invitation to join Britain’s Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park.

There, Tutte’s extraordinary achievement — breaking the complex German Lorenz code without ever seeing the machine that generated it — is said to have hastened the end of the war by about two years and saved millions of lives.

According to Bletchley Park historians, General Dwight D. Eisenhower himself described Tutte’s work as one of the greatest intellectual feats of the Second World War.

The Lorenz code machine — used by Adolf Hitler and senior members of the German High Command to communicate high-level strategy — was believed to be unbreakable and trusted with the most sensitive, highly strategic information. Alan Turing’s Enigma, on the other hand, was used to send tactical messages between individual formations and units, notably ships and submarines.

“Bill Tutte cracked the German Lorenz code, which was vastly more complex than Enigma and strategically much more important."

RICHARD FLETCHER, secretary of the Bill Tutte Memorial Fund in Newmarket, England

“However, for continuing Cold War security reasons his achievement was not publicly acknowledged, while Turing went on to dominate the history of Bletchley Park, largely as a result of the tragic circumstances of his death.”

Tutte’s silence, which endured for decades, demonstrates enormous strength of character. Yet it was also, quite simply, part of the job. He and his colleagues at Bletchley were bound under the Official Secrets Act of Britain, which made it an act of treason to reveal what they knew. His story did not come out until the late 1990s and then only by accident. It wasn’t until 2012 that Prime Minister David Cameron publicly acknowledged the debt owed to him.

“Like all of them at Bletchley Park, they were all told never to talk about it. Churchill called them the geese that laid the golden eggs but never cackled, Bill Tutte not only never mentioned his wartime work at any stage — even after becoming a famous mathematician in Waterloo — he saw all the hype going on about Turing and remained silent."

RICHARD FLETCHER, secretary of the Bill Tutte Memorial Fund in Newmarket, England

Dan Younger, who was a graduate student in the early ’60s when he first heard Tutte speak and later became a faculty colleague and close friend, confirms how closely those secrets were held.

“One of the ways we got to know each other was through hiking along the rivers in Waterloo region and around [West Montrose, where Tutte lived with his wife Dorothea until her death in 1994],” says Younger, a professor emeritus in the Faculty of Mathematics.

“He was a lover of wildflowers and he would soak up the wonder of them on our hikes. He was a very knowledgeable person in many different areas: about history, astronomy, almost every area of human knowledge. It was always fun to be with him.

“He was a fairly quiet person and I’m an inquisitive person, and in all those years hiking together he never ever told the secret of what he’d done in the war. [Hollywood] should do a movie because Tutte’s contribution was of a greater scope than Alan Turing’s, there’s no doubt about that."

DAN YOUNGER, student, colleague and friend

Stories about Tutte’s role began to emerge in the mid-1990s, and although he did eventually receive formal recognition as an Officer of the Order of Canada, this didn’t happen until October 2001 — only a few months before he died. It wasn’t until 2011 that Tutte’s feat garnered public attention through the BBC documentary, The Lost Heroes of Bletchley Park .

“He did say that to finally be able to tell the story removed an enormous pressure that had been on him all those years,” Younger says. “He was very proud of the fact that it finally came out, and wanted to share it with me. I think [the British government] made it a mistake in keeping it a secret for so long.”

Tutte’s efforts were especially critical in the latter part of the war, Younger explains. Between November 1942 and May 1945, more than 13,500 Lorenz messages were deciphered at Bletchley, allowing the Allies to pinpoint the positioning of Nazi units.

In fact, the Allied invasion of Normandy was successful partly because Tutte and his colleagues had intercepted Nazi communications showing the Germans were expecting an invasion at a different location.

Cracking the code was indeed a herculean effort, but Tutte was a modest man.

“He would’ve emphasized the fact that he was part of a larger effort, but he was also extremely proud that the Canadian government honoured him with the Order of Canada,” Younger says. “He wanted to be recognized for what he did. He was fortunate that he lived just long enough to tell the story and to be recognized for that story.”

That Tutte isn’t yet a household name is something a handful of passionate British historians are trying to rectify.

The Bill Tutte Memorial in Newmarket’s town centre was unveiled this past September as a way to pay tribute to the man and to raise awareness of Tutte’s contributions to code breaking and mathematics.

A memorial fund in Tutte’s name (donations to which can be made online) has also been established to help promising young students of modest means to further their studies in mathematics or computer science.

Newmarket’s Fitzroy House is the birthplace of Bill Tutte, where Tutte’s father William worked as the gardener and his mother Annie the housekeeper. Today, Fitzroy House is one of Britain’s most picturesque and historic racing yards, home to dozens of champion racehorses. (Photo courtesy of Michael Bell)

Tutte (bottom row, far right) is pictured with his classmates at Cheveley Village School in 1923. (Photo courtesy of Sylvia Greening)

It was Tutte’s interest in mathematical puzzles that led to his invitation to join the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park, where he was based in the Testery in F Block (now demolished). (Photo by J. E. Hoad, with the permission of the Bletchley Park Trust)

The four-rotor naval Enigma (left) used Morse code and the 26-letter alphabet, whereas the vastly more complex German Lorenz cipher encrypted messages that were sent by radio teleprinter using Baudot code. Tutte is credited with cracking the Lorenz code. (Photos courtesy of Claire Butterfield)

The mathematician circa 1968 near his home in West Montrose. (Photo courtesy of Richard Youlden)

Tutte was made an Officer in the Order of Canada in 2001, shortly before he died in 2002.

Read more

Redefining capstone learning by bringing students, faculty and community partners together to tackle real-world challenges

Read more

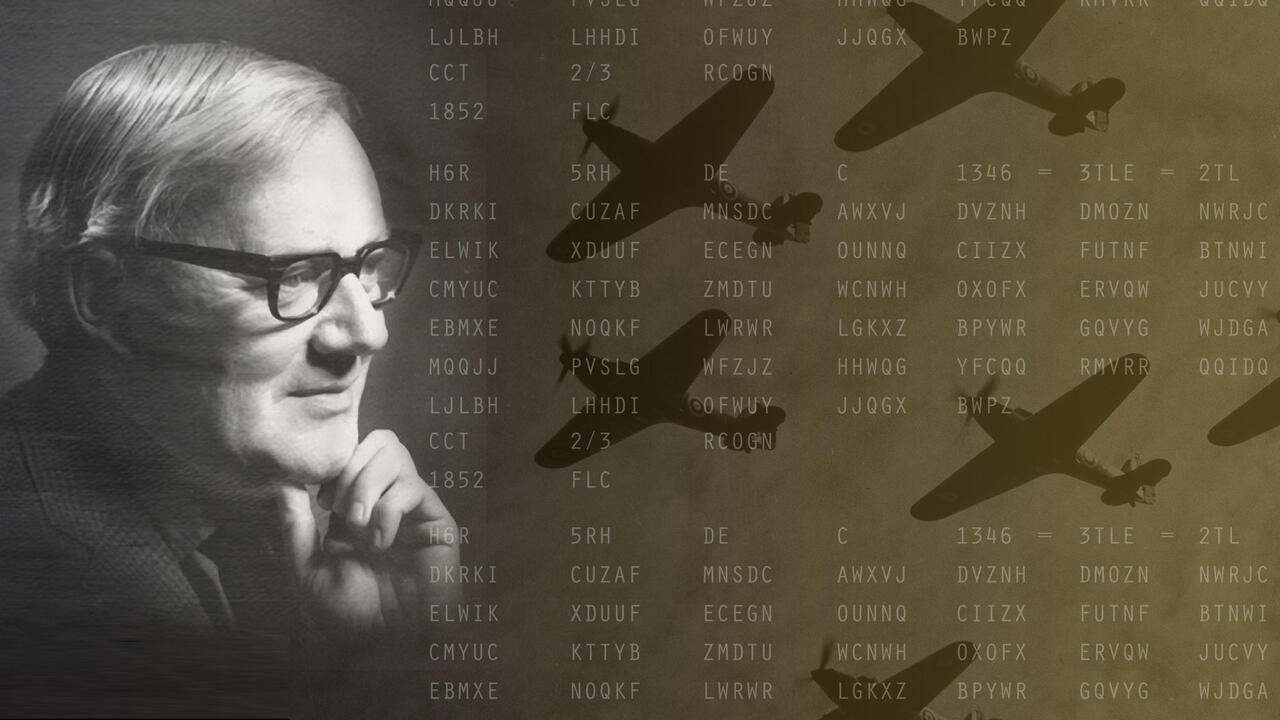

How machine learning empowers collaboration between computer science, math and medical research

Read more

Here are the people and events behind some of this year’s most compelling Waterloo stories

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.