Researchers aim to free diabetics from painful finger pricks

Wearable radar and AI technologies being developed at the University of Waterloo would monitor blood sugar without drawing blood.

Wearable radar and AI technologies being developed at the University of Waterloo would monitor blood sugar without drawing blood.

By Brian Caldwell Faculty of EngineeringResearchers at the University of Waterloo are developing new technology that would free people with diabetes from painful finger pricks to monitor their blood sugar.

A team led by engineering professor George Shaker has combined radar and artificial intelligence (AI) to detect changes in glucose levels without the need to draw blood several times a day.

“We want to sense blood inside the body without actually having to sample any fluid,” says Shaker, who is cross-appointed to mechanical and mechatronics engineering, and electrical and computer engineering. “Our hope is this can be realized as a smartwatch to continuously monitor glucose.”

The research involves collaboration with Google and German hardware company Infineon, which jointly developed a small radar device and sought input from select teams around the world on potential applications.

The system under development uses the radar device to send high-frequency radio waves into liquids containing various levels of glucose and receive radio waves that are reflected back to it.

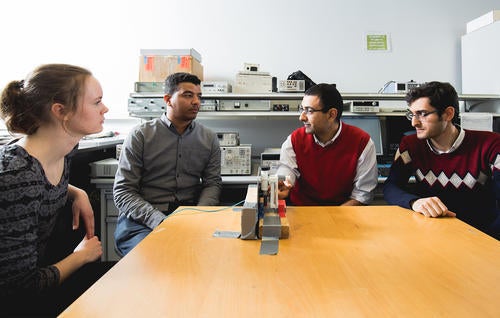

George Shaker (second from right) discusses research into the development of a glucose monitoring system for diabetics with students (left to right) Karly Smith, Ala Eldin Omer and Mostafa Alizadeh.

Information on the reflected waves is then converted into digital data for analysis by machine-learning AI algorithms developed by the researchers.

The software is capable of detecting glucose changes based on more than 500 wave features or characteristics, including how long it takes for them to bounce back to the device.

Initial tests with volunteers at the Research Institute for Aging in Waterloo achieved results that were 85 per cent as accurate as traditional, invasive blood analysis.

“The correlation was actually amazing,” says Shaker. “We have shown it is possible to use radar to look into blood to detect changes.”

Next steps include refining the system to precisely quantify glucose levels and obtain results through the skin, which complicates the process.

The research team is also working with Infineon to shrink the radar device so that it is both low-cost and low-power.

The data analyzed by AI algorithms is now sent wirelessly to computers, but the ultimate aim is self-contained technology similar to the smartwatches that monitor heart rate.

“I’m hoping we’ll see a wearable device on the market within the next five years,” Shaker says. “There are challenges, but the research has been going at a really good rate.”

Collaborators at Waterloo include electrical and computer engineering professor Safieddin (Ali) Safavi-Naeni, kinesiology professor Richard Hughson and numerous students.

A study on the research, Non-invasive monitoring of glucose level changes utilizing a mm-wave radar system, was published in June in the International Journal of Mobile Human Computer Interaction.

Read more

Two University of Waterloo affiliated health-tech companies secure major provincial investment to bring lifesaving innovations to market

Read more

Researchers engineer bacteria capable of consuming tumours from the inside out

Hand holding small pieces of cut colourful plastic bottles, which Waterloo researchers are now able to convert into high-value products using sunlight. (RecycleMan/Getty Images)

Read more

Sunlight-powered process converts plastic waste into a valuable chemical without added emissions

Read

Engineering stories

Visit

Waterloo Engineering home

Contact

Waterloo Engineering

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.