Julia Hughes, Rachael Driediger, and Isabella Barichello, second-year Biomedical Engineering (BME) undergraduate students, showcase their hands-on design experience in creating a functional EMG-controlled prosthetic hand.

What inspired your design?

We chose to design for transradial amputees because many people with limb loss below the elbow still have strong forearm muscles that can generate clear EMG signals. That meant we could create a prosthetic that tapped into existing muscle control, making it both intuitive and practical to use. At the same time, we saw that commercial prosthetics often fall short; many are expensive, uncomfortable, or lack fine control, leading to high rejection rates. Our project aimed to show that with thoughtful engineering, even a low-cost design could restore meaningful function for this community.

Can you describe your solution?

Our solution was a below-elbow prosthetic arm that responds to muscle signals from the forearm. When the user flexes, electrodes pick up those signals and send them through a small circuit and Arduino, which trigger a motor to pull tendons that close the prosthetic’s fingers. To reopen the hand, the user flexes a second time, which reverses the motor and releases the grip. The design included a fixed thumb and two tendon-driven fingers, shaped to stack cups as a way of mimicking everyday tasks like gripping, lifting, and releasing. Built with 3D-printed parts, an aluminum base, and rubber grips on the fingers, the prototype was both affordable and functional.

What knowledge and skills did you use to develop your solution?

Creating a functional EMG-controlled prosthetic hand from start to finish required a wide range of skills. We started by constructing our mechanical design, circuitry, and Arduino code using various modelling tools to ensure our system functioned properly under simulations. Our mechanical design was created in Autodesk Fusion. While the prosthetic fingers themselves were mostly 3D printed, our design included many small sheet metal parts, which we customized in the machine shop. We also needed circuitry knowledge from our courses this term to apply signal processing to the raw EMG signal. We gained a lot of hands-on experience troubleshooting in the lab through this project. We also used our programming skills to develop code for the Arduino.

Was there a roadblock you hit during the design process and how did you overcome it?

One of the roadblocks we encountered during the design process involved the execution of our mechanical design. Our prosthetic design consisted of two tendon-actuated fingers. The “phalanges” were 3D printed and joined together via waterjet sheet metal. The 3D printed components had been originally modelled for a specific gauge of sheet metal, but at the last moment we had to change the sheet metal gauge. This required us to rework the modelled pieces, but even then the metal still didn’t fit properly with the printed material. To overcome this, we went through several iterations, filing the metal parts down further and experimenting with different adjustments until they fit together as intended. Throughout this process, we relied not only on our own creative problem-solving but also on the insights and suggestions of others, which helped us find a workable solution.

We could create a prosthetic that tapped into existing muscle control, making it both intuitive and practical to use.

What did you learn from testing the design in realistic scenarios?

After initial testing of our prosthetic with a known signal (produced with a function generator), we moved to testing with EMG, which is a more realistic method of actuation for the prosthetic. This process taught us a lot about EMG signals and how difficult they can be to work with, given that raw EMG data is noisy and has a very small amplitude (on the order of ±5mV), which varies depending on the person and electrode placement. Testing with EMG also revealed just how much muscle fatigue diminishes the amplitude of EMG signals, which informed some of our design decisions surrounding the prosthetic’s method of actuation.

Julia, a second-year BME student, filing the sheet metal as part of the design fabrication process.

How did the collaboration in the group shape the final design?

Group collaboration was a driving force behind the success of our prosthetic, influencing our final design from initial brainstorming to final testing. Working in a team meant that we were able to combine our diverse skill sets and technical abilities. Our different strengths ensured that every aspect of our project from mechanical design to signal processing was complete and effective, contributing to a well-rounded final design. This allowed for task delegation as well, increasing our efficiency. As different team members were focused on different aspects, such as electrical circuit development or physical prototype creation, we were able to work in parallel to meet internal deadlines and complete the project. Dividing up the work also permitted us to work on tasks that aligned with our interests, contributing to us all having a strong sense of ownership over the final prosthetic design. Lastly, due to the collaborative nature of our design we all contributed to troubleshooting. Coming together to brainstorm how to overcome various challenges led to quick and efficient problem-solving and let us work on continually improving the prosthetic design.

If you could take this project to the next stage, what improvements or new features would you add?

If we were to take this project to the next stage, we would first replace the breadboard with a custom PCB to improve reliability and signal consistency. Mechanically, redesigning the forearm base to better match individual limb geometry and enclosing exposed electronics would enhance comfort and safety. We would also refine the tendon routing and spring mechanism for smoother finger actuation and add textured silicone grips to improve consistency and durability. These changes would make the prosthetic more user-friendly and closer to real-world application.

Group collaboration was a driving force behind the success of our prosthetic, influencing our final design from initial brainstorming to final testing.

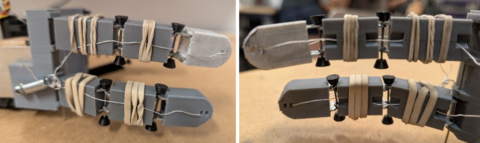

Figure 1. (a) The leftmost image is of the back of the tendon-actuated prosthetic fingers. Notable features include the extension spring at the base of the fingers, the elastic bands holding the tension springs in place against the back of the phalanges, and the holes at the tip of each finger allowing the strings to pass through to the front. (b) The rightmost image is of the front of the tendon-actuated prosthetic fingers. Notable features include the channels in the phalanges, holding the tension spring in place against the fingers, as well as the metal hinge joints, metal joint pins, and pin caps which are used to assembly phalanges together into a moveable finger.

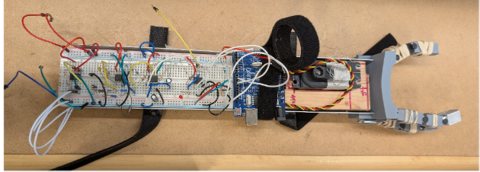

Figure 2. Image of the final functioning prosthetic device with all mechanical elements mentioned included. The electrical and mechanical systems have been merged. The black arrows represent the paths that the tendon-actuated fingers follow during prosthetic operation.