The single-family home has epitomized the American (and Canadian) dream at least since the 1950s when rapid growth occurred at the edges of metropolitan areas in the form of low-density suburbs. However, since then changes in demography, cultural and social values, gender roles, and the structure of cities and housing markets have begun to change the image of single-family home living as the norm.

In many places, the bungalow style single-family house (or other smaller detached homes) is still commonly portrayed as the ‘starter home’ for young families with children—young adults would upgrade to larger homes as they earned more income with experience in the labor market. The attainment of homeownership was, and remains, associated with social status and cultural ideals as well as serving the more practical purpose of a forced retirement savings plan.

This retirement plan looked something along the lines of the following (and still does in some cases): paying down the mortgage, fixing or perhaps even enhancing the home with new features, and eventually downsizing at an older age to retrieve some of the equity in the home for use as income during retirement. The ‘housing-based’ retirement plan only works if prices keep rising.

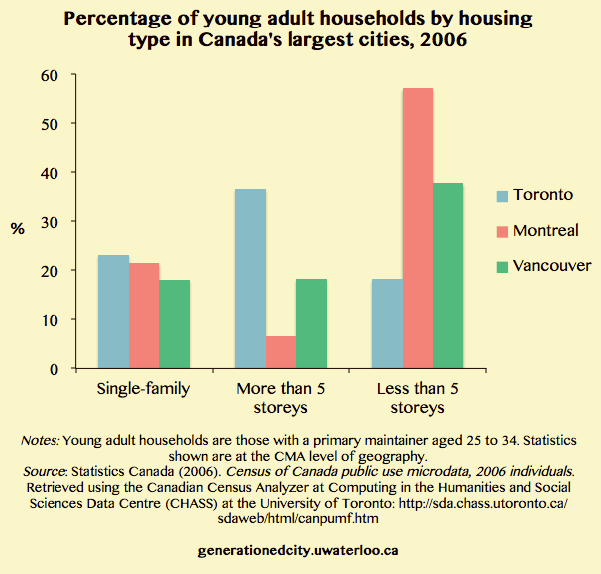

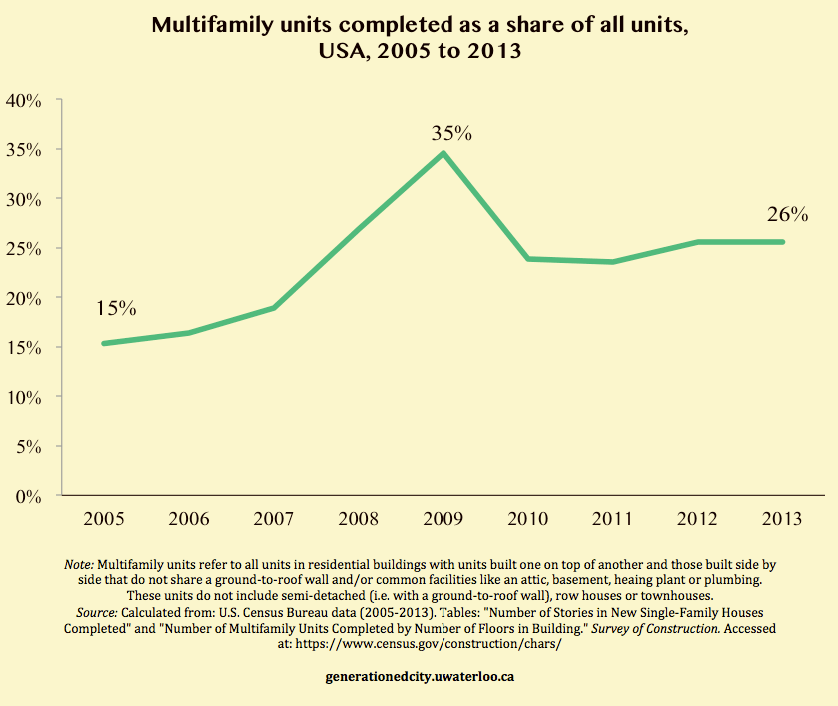

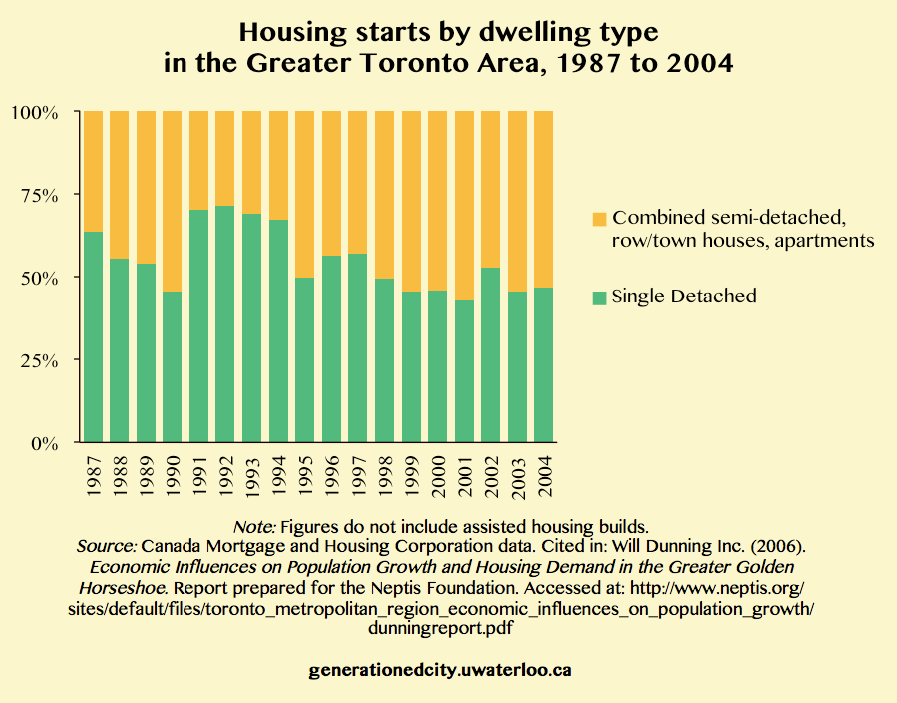

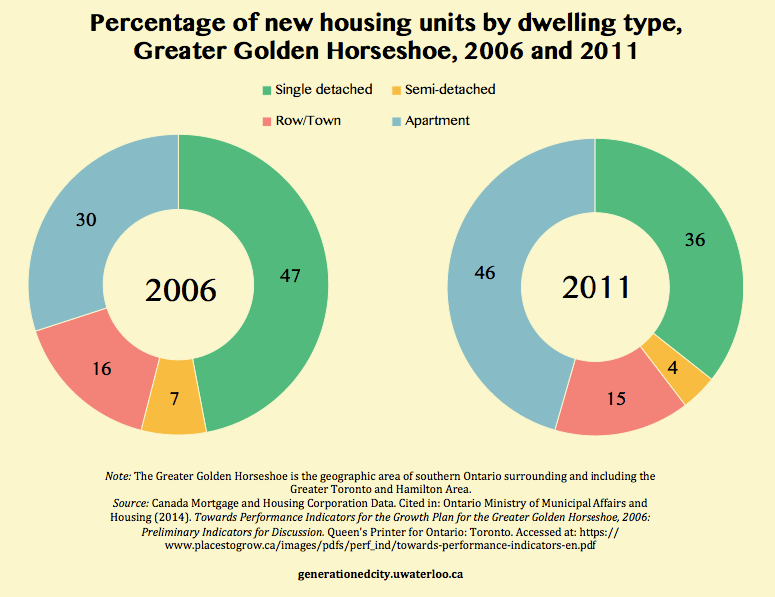

There is increasing evidence that young adults today are not following in the same footsteps as their parents in regards to housing decisions. While homeownership rates have remained remarkably stable given rising affordability concerns, young adults are more likely to purchase into multifamily housing, such as high-rise condominiums, rather than purchasing suburban single-family homes.

Some have argued that the condominium apartment has replaced the bungalow as the ‘starter home’ in some cities. The wide spread assumption (and there is some evidence in our published research to support this) is that young adults are living in small, centrally located apartments until, if ever, their household size grows. Those that remain in high-density areas with spouses and children are believed to be those with higher incomes—they can afford to pay the high price of space in central locations; or those who continue to live alone or with a partner or spouse without children when getting older.

There are also evident geographic differences—it is in the largest, most expensive cities where the growth in multifamily housing is occurring. Whether or not the condominium apartment will ever replace the single-family home in cultural, economic and social significance remains to be seen.

There are several explanations for the changes in housing preferences toward higher density, multifamily, housing options:

- Decreasing household size

- Lower incomes and more temporary, contract jobs increase the share of those renting, and rental supply typically consists of more multifamily housing

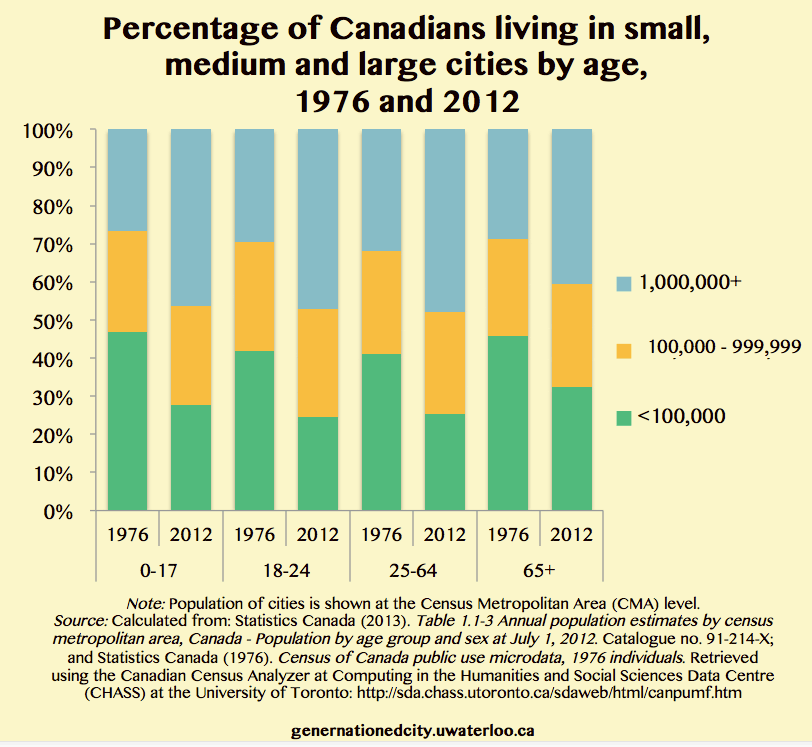

- Urbanization – more people, and particularly young people, living in cities

- Rising prices in large cities leads to affordability concerns. This increases share of renters, and rental supply consists of more multifamily housing

- Moving to ‘high demand’ cities for lifestyle amenities, thus facing steep prices/rents

- Increasing supply of multifamily housing units due to urban growth, rising land values, and/or smart growth planning principles

- Preferences for urban lifestyle where fewer single-family homes are available, or not affordable to young adults

- Preferences for shorter, transit-oriented, walkable or cycling commute facilitated by higher density living

- Proximity to post-secondary educational institutions

We would argue that these are complementary explanations, but that some explanations are more accurate in some cities than others, and the importance would also vary for different kinds of young adults (e.g., by income, gender, race, ethnicity etc.).

At Generationed City we hope to shed more light on the relative importance of these explanations in different places and for different kinds of young adults through our research.