There is growing concern that housing is becoming less affordable to young adults in North America. While there is certainly a wealth of research on emerging employment and housing challenges, surprisingly little of this research focuses on young adults. Here we describe the trends that are commonly believed to contribute to affordability challenges. This is a starting point for our research to collect more systematic evidence on these issues—in particular, we aim to move from simply documenting the trends toward gaining an understanding of the factors behind increasing affordability and employment concerns, and in what ways do they shape young adults’ opportunities.

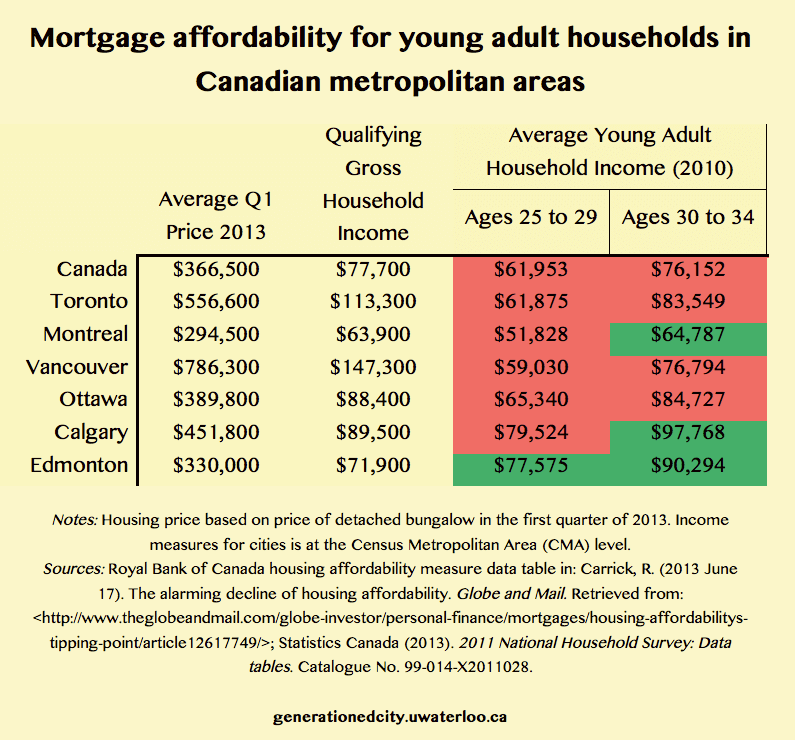

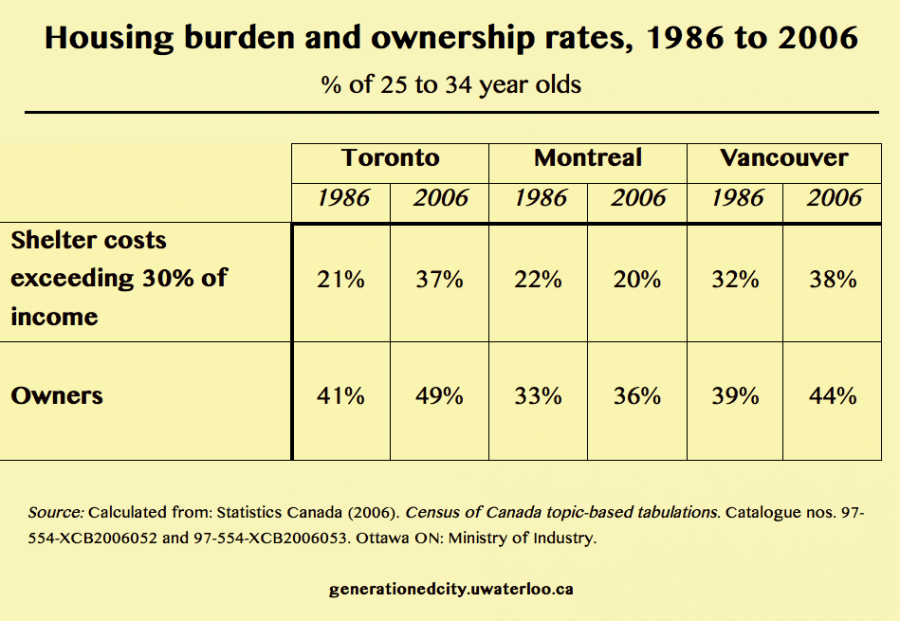

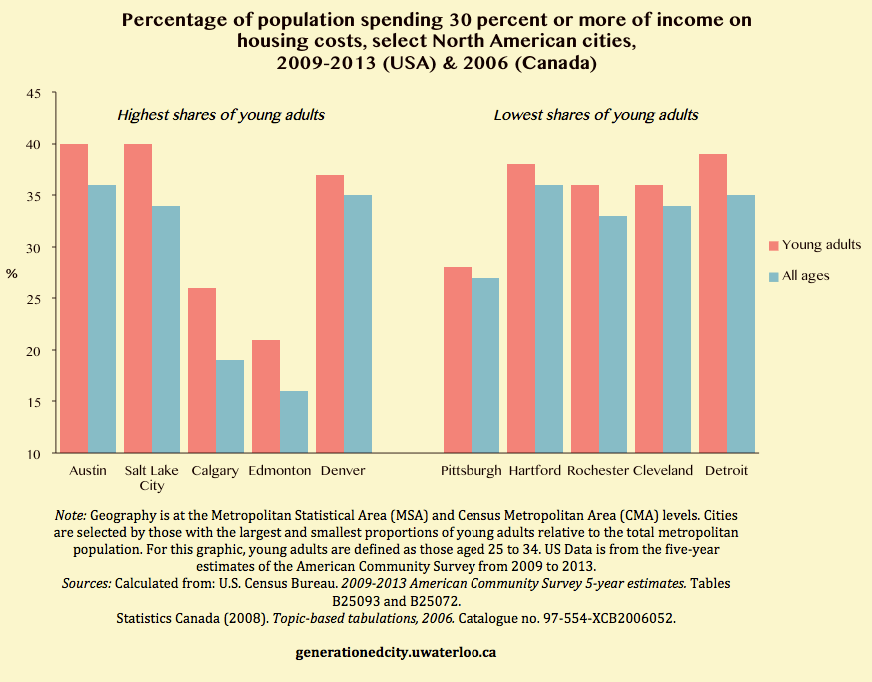

One the one hand, prices and rents have certainly increased in large metropolitan areas experiencing population and economic growth such as New York, Los Angeles, Toronto or Vancouver. This would make it more difficult for young adults just starting out to enter the housing market on their own.

On the other hand, interest rates have been particularly low in recent years. This should, at least in theory, make it easier for young adults to enter housing markets.

One might also argue that in cities experiencing housing price increases due to economic growth, we should see incomes rise as well. At the same time, there are several markets where prices have not increased as much, or even decreased, due to economic decline such as in cities in the industrial rust belt, or due to the recent recession.

However, there are several reasons why housing affordability is generally believed to have decreased over time for young adults in most cities. First, in the cities experiencing declining or stable housing prices, job opportunities are generally also scarcer, unemployment rates are higher, and income growth is moderate at best. In these cases, lower housing costs simply mirror lower economic prospects and spending power.

Second, due to the increases in educational attainment, and concurrent student debt, it has been argued that young adults are finding it more difficult today to come up with a down payment for a home. If this is indeed the case, low interest rates on financing would not benefit young adults if a larger share of them cannot obtain mortgage credit in the first place.

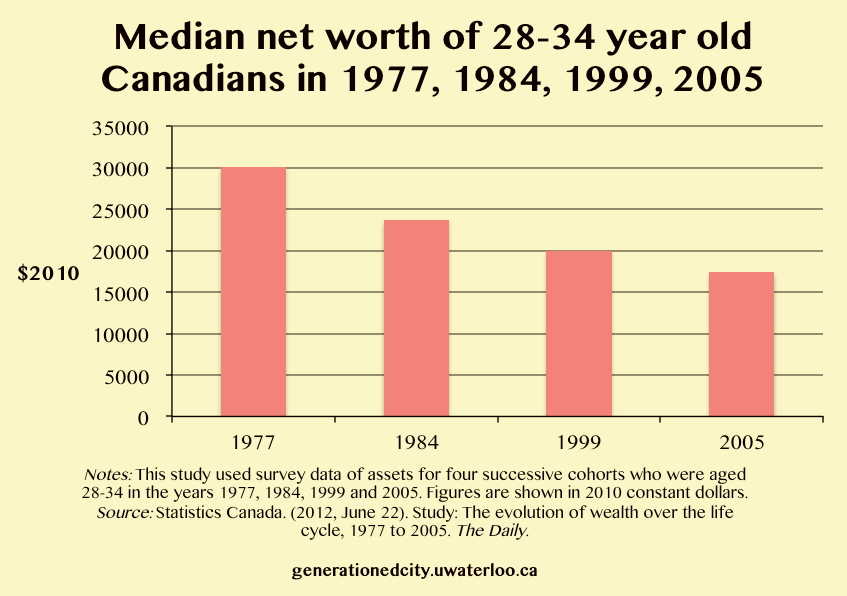

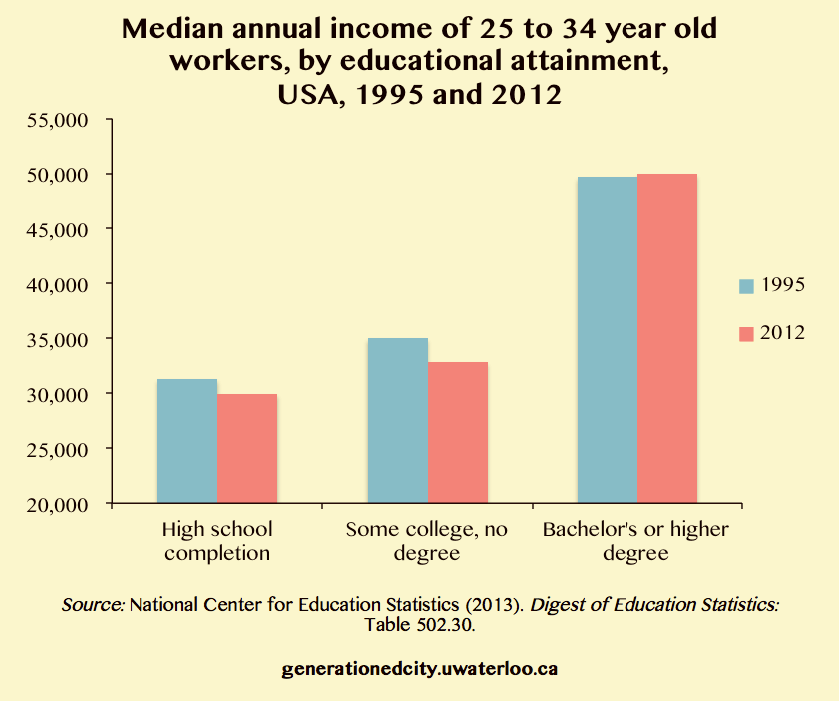

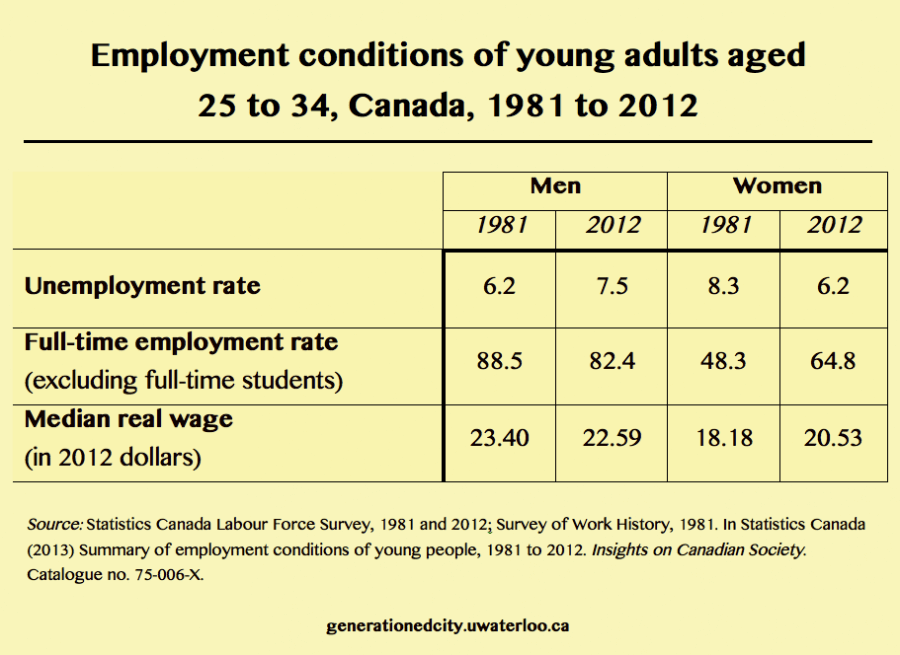

Third, there is increasing evidence that the earnings of young adults have not kept pace with economic growth. Several studies, including those conducted by Generationed City researchers, show that young adults today are earning less than someone in a similar job, with a similar education and a similar demographic profile did thirty to forty years ago.

Fourth, the dismantling of government programs since the late 1970s have reduced the assistance for social and assisted housing—a shift noticeable in the U.S. and Canada. But in the latter the changes were perhaps even more pronounced since Canada had quite an elaborate housing policy system before it was subject to restructuring at all levels of government. This is often believed to have dramatically reduced the supply of affordable housing.

Fifth, the free-market and small government ideologies that contributed to a reduction of government assistance and programs also altered labor markets. A decline in unionization rates and permanent and full-time jobs is commonly argued to have created increasing employment insecurities and declining opportunities to earn a stable income for workers. These changes, along with other factors, are commonly argued to have contributed to increasing concerns over income inequality that materialized in the Occupy Wall Street Movement and also the recent fast-food worker protests.

At Generationed City we aim to add more evidence to this debate. We will collect systematic evidence and analyze existing data on these trends, as well as the reasons driving the changes across North American cities. This way we will be able to say more definitively what factors contribute to declining employment prospects and housing affordability concerns among young adults, why, and whether the challenges have actually increased over time.