This case study was written by Nancy Goucher in 2004 as part of her fourth year undergraduate degree. More info is provided in the full report. The full list of citations are also provided in the report.

Image source: Goucher

Introduction

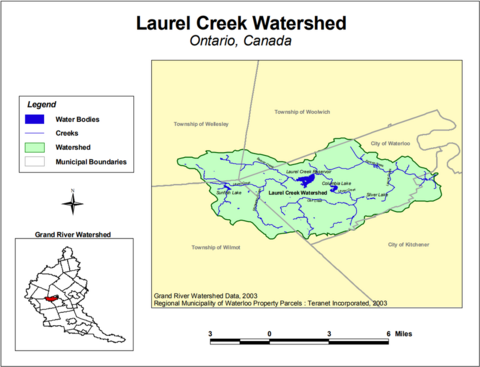

Laurel Creek is a tributary of the Grand River, one of the largest rivers in southern Ontario. The Laurel Creek watershed (LCW) is a fertile, diverse area rich with aquifers supporting the storage of groundwater, interesting terrestrial resources, and diverse species habitat. Most of the LCW is located within the city of Waterloo; watershed planning, however, is conducted by the Grand River Conservation Authority (GRCA) at the Grand River watershed scale.

The Laurel Creek watershed is located in southwestern Ontario, Canada. The creek drains an area of 74.4 km2 (28.7 mile2 ) into the Grand River, which continues to Lake Erie. The Laurel Creek watershed is located at the northwestern end of the regional municipality of Waterloo

Image source: Goucher

The largest municipality in the watershed is the city of Waterloo. Eighty percent of the city is drained by Laurel Creek (Grand River Watershed Data, 2003). In 2003, the city of Waterloo had a permanent population, excluding students, of 87,874 (City of Waterloo, 2003c). Between 2001 and 2002, the city’s population increased by 3.4 percent (Region of Waterloo, 2003).

Laurel Creek’s headwaters begin in rural landscapes of the township of Woolwich and Wellesley and drain into the Grand River in the city of Kitchener at Bridgeport Road. Laurel Creek’s main tributaries include Clair Creek, Forwell Creek, Beaver Creek, and Monastery Creek, all of which have major sections running through the city of Waterloo (GRCA, 1993).

The watershed is characterized by well-drained soils and moraines that enable groundwater recharge and the sustainability of relatively large aquifer systems. In its original state, the groundwater would contribute to the base flow of Laurel Creek and its tributaries to provide for productive coldwater fisheries. The moraine system also supports a wide range of plant, animal, and bird species.

Geology

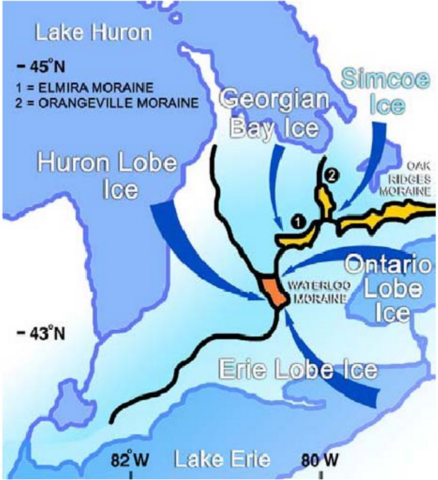

The long-term geologic history, including past glacial activity, has affected the current LCW landscape. Waterloo’s underlying bedrock was created during the Silurian Period 430 to 395 million years ago when sediments were deposited in the ancient Silurian and Devonian seas that once covered much of southern Ontario (Nelson et al., 2003). These compressed sediments created a Salina Formation consisting of interbedded gray to green shale, mudstone, dolomite, salt, and gypsum. In the past two million to 11,000 years ago, a number of glacial advances and retreats of the Erie-Ontario and Huron–Georgian Bay ice lobes resulted in between 45 and 100 meters of glacial deposits left on top of the bedrock. See Figure 3. The quaternary geology of the watershed is mostly kame and till. Kames are glacial stream deposits of mostly sand and gravel. In the LCW, kames formed a “hummocky” topography in the west end with numerous small hills and depressions. Till plains are relatively flat with mixed sand, clay, and gravel resulting from glacial advances carrying forward a mix of debris. The LCW also has small areas of outwash, or material deposited by glacial meltwater streams, and “alluvium,” or unconsolidated materials recently deposited by rivers and streams (GRCA, 1993).

The kame deposits have created the most significant landscape in the watershed, which is generally called the Waterloo Moraine or Sandhills. This moraine provides opportunity for large aquifers and groundwater recharge and is not only important as a groundwater recharge zone to the LCW, but also to the entire Grand River watershed (GRW). The Waterloo Moraine provides drinking water for at least 300,000 people in the Waterloo region (City of Waterloo, 2003a). Furthermore, numerous spring-fed wetlands and small ponds dot the area.

Image source: Goucher

Image source: Johannes Plenio

Vegetation

In pre-European times, dense forest and extensive marsh wetland dominated the watershed. In fact, 91.3 percent of Waterloo county consisted of nonwetland woodland around 1800 (Larson, 1999). The LCW lies within the Mixed Deciduous and Coniferous Forest Zone. Original vegetation included a mix of upland and lowland species and coniferous and deciduous forests. Common native trees include aspen, beech, Manitoba maple, oak, and white pine (Nelson et al., 2003).

Originally, the area was also rich with wildlife. Mammals there would have included black bears, bobcats, cougars, gray foxes, lynx, raccoons, white-tailed deer, wolves, and woodland caribou. Birds would have included bald eagles, Canada geese, great blue herons, hooded warblers, least bitterns, Louisiana waterthrushes, northern cardinal, short-eared owls, and redheaded woodpeckers. When the streams were cool and high in oxygen, fish such as bluegill, brown trout, perch, redside dace, salmon, and walleye were common (Nelson et al., 2003).

Image source: University of Waterloo Library

Laurel Creek in Early Years

Laurel Creek’s headwaters begin in rural landscapes of the township of Woolwich and Wellesley and drain into the Grand River in the city of Kitchener at Bridgeport Road. Laurel Creek’s main tributaries include Clair Creek, Forwell Creek, Beaver Creek, and Monastery Creek, all of which have major sections running through the city of Waterloo (GRCA, 1993).

The watershed is characterized by well-drained soils and moraines that enable groundwater recharge and the sustainability of relatively large aquifer systems. In its original state, the groundwater would contribute to the base flow of Laurel Creek and its tributaries to provide for productive coldwater fisheries. The moraine system also supports a wide range of plant, animal, and bird species.

Image source: ARTS 490

Present-Day Laurel Creek

Laurel Creek begins in a rural landscape and flows through a few woodlands and wetlands. Agricultural land uses contribute to the degradation of the stream as fields’ edges abut the course allowing for livestock grazing around and in the water. In addition to the resulting soil erosion, runoff of pesticides, fertilizers, and other chemicals is a concern. The creek then flows into Laurel Creek Reservoir, which was specifically built in 1966 to contain heavy stream flows. Here, the water slows, the silt and contaminants are dropped, and the temperature of the water increases because of lack of shade and the shallowness of the lake. Challenges here include water weeds and hundreds of ducks and geese and their waste products. Laurel Creek then cools a little as it leaves the reservoir and some groundwater infiltrates the stream, but it warms again when it travels through Columbia Lake and the ponds on the University of Waterloo campus. Laurel Creek then continues to Silver Lake in UpTown Waterloo. Here too warming water, ducks and geese, and nutrient and silt accumulation prove problematic. A 500-meter (1640-foot) culvert then takes the creek underground, where it emerges beside the Waterloo City Centre. The final stretch includes some shade and attractive components, where 14 the water cools slightly. Because some buildings are quite close to the waterway, however, erosion is a problem. In addition, people have used the creek as a dumping ground for yard waste and hazardous household products (GRCA, 1993).

Modifications of Laurel Creek

Between 1948 and 1982, a number of structural flood/erosion controls, including diking, channel improvements, and bank stabilization, were used throughout the entire Grand River watershed. From an engineering perspective, building dikes and channelizing creeks increased a river’s capacity to handle peak flows. Channel improvements, meant to remove obstructions and straighten, deepen, widen, and line the channel with materials such as concrete, were thought to increase hydraulic efficiency and to provide erosion control. Laurel Creek is one of the waterways within the Grand River watershed to undergo such changes to its structure (GRCA, 1983). In 1966, Laurel Creek Reservoir was built by the GRCA as a floodwater storage structure. Built to control flood flows with the intent of reducing flood risk downstream, today it is the centerpiece of the Laurel Creek Conservation Area managed by the GRCA. Lands for the conservation area were bought mainly for flood control purposes, but the area has come to be valued as open space in the midst of rapid urban development. Columbia Lake and Laurel Lake were also built around this time, more so for aesthetic reasons than for flood control (GRCA, 1993). Although structural approaches are somewhat effective, a lot of credit for reducing flood damage and increasing water quality has been attributed to watershed planning and floodplain management (City of Waterloo, 2003a).

NGOs and Laurel Creek Management

A number of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are involved in the management of Laurel Creek. Some of these groups are action-oriented and others are lobbying the government take action to better protect the integrity of the watershed.

The Laurel Creek Citizens Committee (LCCC) was initiated by concerned citizens in 1990 to protect, rehabilitate, and enhance Laurel Creek. Today, the city of Waterloo, the Grand Creek Conservation Authority, and local environmental consulting firms support the LCCC with advice, funding, and administrative support, but the work is conducted by approximately eighty members.

Furthermore, the city of Waterloo invites the LCCC as well as other NGOs such as the Waterloo Citizen’s Environmental Committee to participate in steering committees for studies done in the subwatershed studies for the LCW and the rest of the city.

Other NGOs are involved in lobbying city council to protect, enhance, and rehabilitate the watershed. For example, Get Rid of Urban Pesticides (GROUP), a volunteer organization, initiated a campaign in 2001 to help homeowners wean themselves off of pesticides. The campaign was a response to the increasing concerns people had about the use of pesticides on urban lawns. GROUP conducts workshops on natural lawn care and distributes educational material to assist in its mandate of creating a healthier and safer pesticide-free community (Koswan, 2003).

Other NGOs in the area are concerned with stewardship of the watershed. For example, the Kitchener-Waterloo Field Naturalists oppose the sale of conservation lands for development (Kitchener-Waterloo Field Naturalists, 2003).