Pedagogy of the streets

Dr. Adam Ellis developing radical approach to teaching and learning

Dr. Adam Ellis developing radical approach to teaching and learning

By Jon Parsons University Relations“I grew up on the margins,” he says. “I was in a school system that wasn’t built for success, or was built for success for some people and not others. The seed was planted for me to think about pedagogy way back then.”

In his work as an assistant professor in the Department of Sociology and Legal Studies, Dr. Adam Ellis is now practicing an approach to teaching and learning that aims to undo the very systems that pushed him to the margins, a liberatory pedagogy he is developing organically.

“Growing up in an environment and a system that had already labelled me a failure, I started to believe that higher education was never an option,” he continues. “I lost hope. That’s when I got involved in the streets and I got involved in gangs.”

Dr. Adam Ellis, founder of The Street Institute, a research hub for critical scholars and community activists who have direct knowledge and experiences of life on the streets.

Ellis is currently teaching a criminology course focused on gangs and street culture. He has a forthcoming book that he co-edited called Thug Criminology: A Call to Action, to be published through University of Toronto Press. Ellis is the founder of The Street Institute, a research hub for critical scholars and community activists who have direct knowledge and experiences of life on the streets.

“At that point, during high school when I was involved in the streets and gang life, it was a situation where my friends and I were socialized to the idea that life was a dead end, with death or jail being the only options,” he says. “It was a disaster. I reflect now and think, when I create classrooms, how can I create systems of care for students?”

Ellis opens his course by narrating his own lived experience of the streets. He describes his values as a teacher and how he intends to support the class.

Then, he organizes the students into their own fictional ‘gangs.’

“Alright, you’re no longer Jeremy, I say. Now you need a street name or an AKA. And this is your new group, and you all need to come up with a name for your gang. We go through a process of identity transformation, as if it was happening in the streets. That’s who they are for this semester, because I want them to start living, feeling and learning like they are the gang.”

As for assessment, Ellis looks to further the experience of the streets. Along with regular readings and weekly reflective writing, students engage in arts-based and ethnographic work. It may be the creation of murals and graffiti about systemic racism, police violence and death and loss. It may be developing hip hop or rap songs about street trauma. It may be creating clothing or styles. In this sense, students analyze the gang and street culture they are immersed in and co-creating.

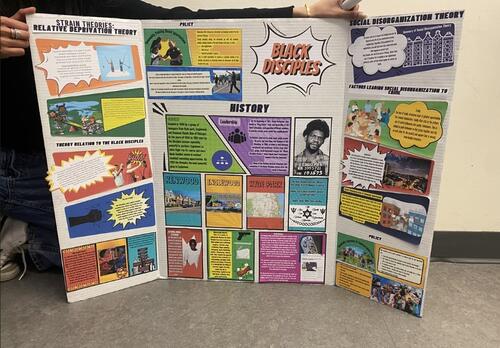

A student poster from the end-of-term course conference Ellis organizes in his class.

Ellis is keen to point out that the course isn’t an attempt to glamorize gang culture. Rather, the whole purpose is to challenge taken-for-granted notions of what gangs are, why people join them and the function they serve in marginalized communities.

“By the end of the term, the whole journey is to see the arc of a person’s life and tell a story of a young person and why they wanted to join a gang,” Ellis says.

While he is committed to developing his teaching practice, it’s not something he has been specifically trained in. In fact, Ellis’ pedagogy flows from his desire to open education to people who grew up like him, so that anyone could have a successful educational experience.

He says he is doing his best to integrate Indigenous approaches to decolonizing pedagogy, and says his work with Jessica Rumboldt, an educational developer specializing in Indigenous knowledges at Waterloo’s Centre for Teaching Excellence, has been highly influential.

Ellis’ teaching practice also has echoes of some of the best-known liberatory pedagogues: Paulo Freire’s pedagogy of the oppressed, Augusto Boal’s aesthetics of the oppressed and bell hooks’ pedagogy of hope, to name a few.

In the Canadian teaching and learning context, it is easy to see in Ellis’ work various elements of Max van Manen’s famous work on the tact of teaching and Carl Leggo’s contributions to artography.

Yet for all the synergies, Ellis develops his own teaching practice organically.

“I don’t study pedagogy,” he says. “Not that I’m not interested, and I am starting to learn more about pedagogy, but I just know what in my mind would have worked for my community and the people I was around to get them excited about education.”

“I’m looking at how I can get students to engage with the arts, especially urban arts, to start thinking about rewriting history, engaging in allyship and to learn how to empower themselves and tell their own stories.”

Read more

Waterloo’s institutional response to ChatGPT

Read more

Introducing the 2023 Global Futures: Innovation Update

Read more

Recent philosophy PhD graduate breaking new ground in disability studies

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.