Better breast cancer screening

Inexpensive new technology promises benefits including more frequent tests, earlier detection and enormous health-care savings

Inexpensive new technology promises benefits including more frequent tests, earlier detection and enormous health-care savings

By Brian Caldwell Faculty of EngineeringResearchers at Waterloo Engineering have developed new, inexpensive technology that could save lives and money by routinely screening women for breast cancer without exposure to radiation.

The system uses harmless microwaves and artificial intelligence (AI) software to detect even small, early stage tumors within minutes.

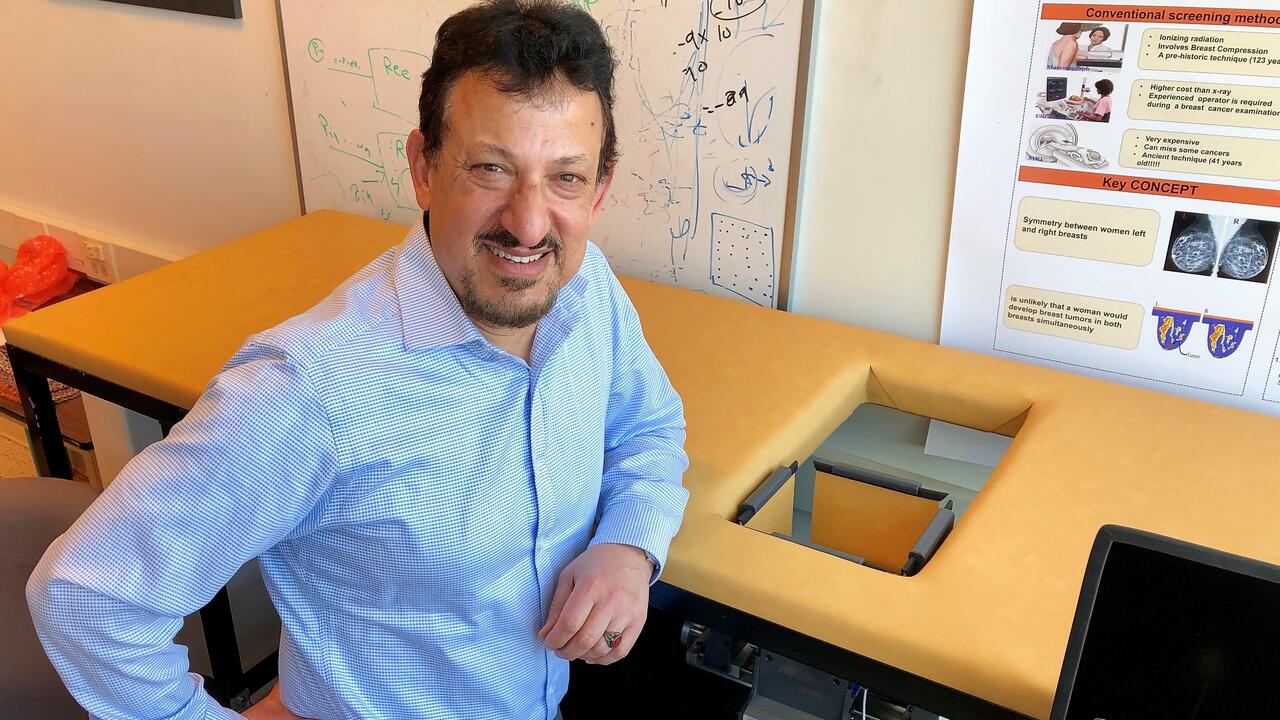

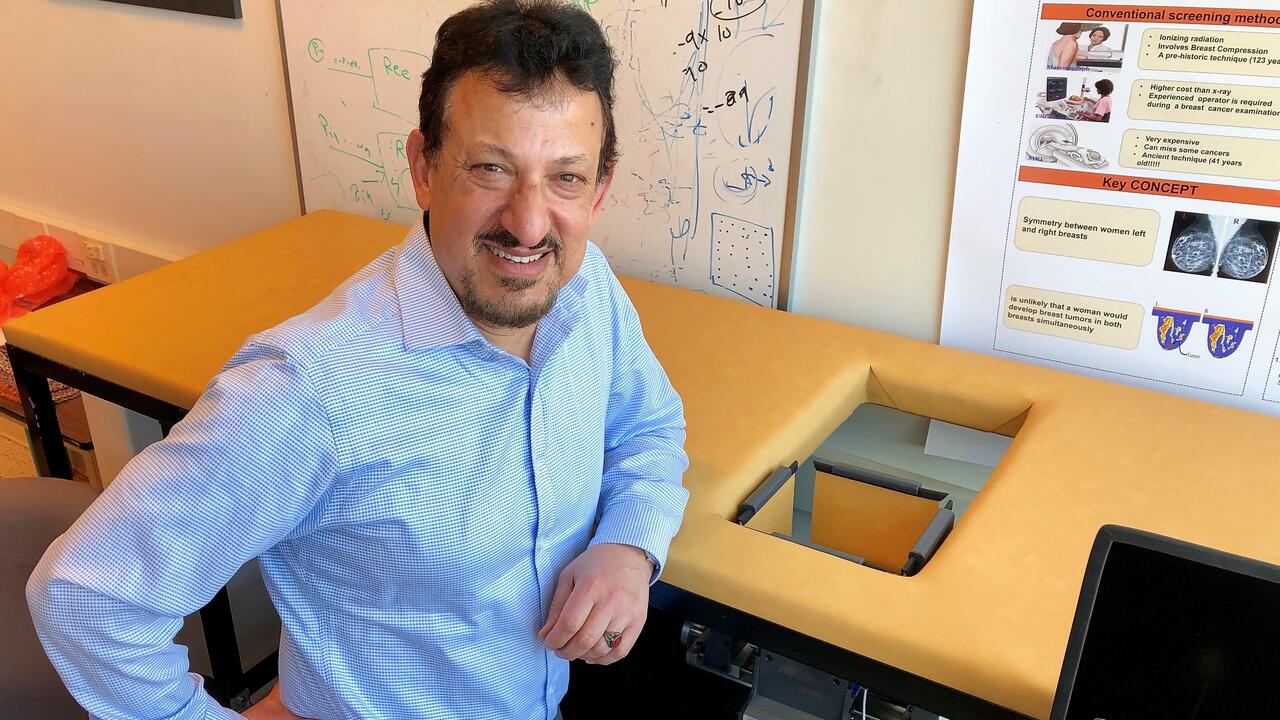

“Our top priorities were to make this detection-based modality fast and inexpensive,” says Omar Ramahi, a professor of electrical and computer engineering. “We have incredibly encouraging results and we believe that is because of its simplicity.”

A prototype device - the culmination of 15 years of work on the use of microwaves for tumor detection, not imaging - cost less than $5,000 to build.

It consists of a flat sensor in an adjustable box about 15 centimetres square that is situated under an opening in a padded examination table.

Patients lie face-down on the table so that one breast at a time is positioned in the box. The sensor emits microwaves that bounce back and are then processed by AI software on a laptop computer.

By comparing the tissue composition of one breast with the other, the system is sensitive enough to detect anomalies less than one centimeter in diameter.

Ramahi says a negative result could quickly rule out cancer, while a positive result would trigger referral for more expensive tests using mammography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

“If women were screened regularly with this, potential problems would be caught much sooner – in the early stages of cancer,” he says. “Our system can complement existing technology, reserving much more expensive options for when they’re really needed.

“We need a mixture, a combination of technologies. When our device sent up a red flag, it would mean more investigation was warranted.”

In addition to reducing patient wait times and enabling earlier diagnosis, Ramahi says, the device would eliminate radiation exposure, improve patient comfort and work on particularly dense breasts, a problem with mammograms.

It would also save health-care systems enormous amounts of money and, because of its low cost and ease of use, dramatically increase access to screening in the developing world.

Researchers have applied for a patent and started a company, Wave Intelligence Inc. of Waterloo, to commercialize the system and hope to start trials on patients within six months. Three rounds of preliminary testing included the use of artificial human torsos known as phantoms.

The latest in a series of papers on the research, Breast Tumor Diagnosis using Machine Learning with Microwave Probes, was presented at a recent conference in Yemen.

Ramahi’s collaborators include engineering PhD student Maged Aldhaeebi, and former PhD students Thamer Almoneef and Hussein Attia.

Read more

Researchers engineer bacteria capable of consuming tumours from the inside out

Hand holding small pieces of cut colourful plastic bottles, which Waterloo researchers are now able to convert into high-value products using sunlight. (RecycleMan/Getty Images)

Read more

Sunlight-powered process converts plastic waste into a valuable chemical without added emissions

University of Waterloo researchers Olga Ibragimova (left) and Dr. Chrystopher Nehaniv found that symmetry is the key to composing great melodies. (Amanda Brown/University of Waterloo)

Read more

University of Waterloo researchers uncover the hidden mathematical equations in musical melodies

Read

Engineering stories

Visit

Waterloo Engineering home

Contact

Waterloo Engineering

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.