Building on 50 years of experience

Waterloo’s School of Architecture marks its golden anniversary as an international leader in design and research

Waterloo’s School of Architecture marks its golden anniversary as an international leader in design and research

By Carol Truemner Faculty of EngineeringIn 1967, Canada celebrated its Centennial year, the University of Waterloo commemorated its 10th anniversary and Waterloo’s School of Architecture launched as part of the Faculty of Engineering.

To mark its 50th anniversary, Architecture hosted a special evening in June for students, faculty and alumni.

Fittingly, the event included the naming of the school’s main lecture theatre in honour of Laurence (Larry) A. Cummings. In the mid-1960s, Cummings presented the motion at the University of Waterloo Senate to create the Architecture program. Along with professors Murray McQuarrie and Robert Wiljer, he co-founded Architecture’s cultural history stream.

The evening also included the kickoff of Architecture’s 50th Anniversary Lecture Series by Brigitte Shim and Howard Sutcliffe. As founders of Shim Sutcliffe Architects, one of the most distinguished design firms in Canada, the architects, both BArch ’83, are among the many hundreds of exceptional alumni Waterloo’s program has produced over the past five decades.

In the 50th anniversary lecture, Shim recalled that when she was a student the program’s studio space was off campus on Phillip Street in largely unheated industrial buildings that had steel columns, concrete floors and bleachers. Indoor bike races often took place there in the winter and oil changes for pickup trucks in the summer.

“The building was an unlikely place for such intense discussions about the interplay between architecture, urbanism and society,” she told the audience.

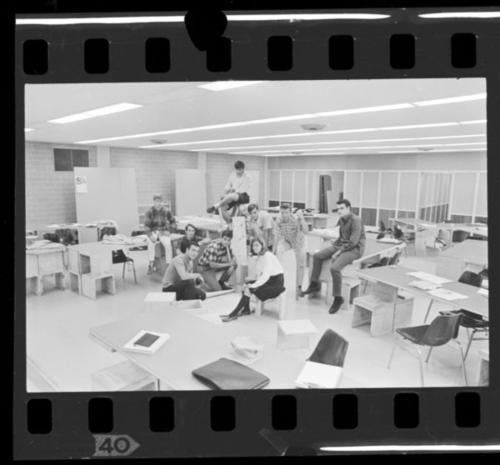

This photograph of an architecture do-it-yourself classroom project was taken when the School of Architecture was founded in September 1967.

Rick Haldenby has similar memories of the Phillip Street studios. A member of an early Architecture class, he graduated with a BArch in 1975. Before the ink on his degree was dry, he was asked to fill in for an ailing professor and teach a couple of courses. Although he had some doubts about whether teaching was for him, he was persuaded to stay on as a faculty member, a position he still holds. From 1988 until 2013, he was director of the school.

"I stuck around because I thought Waterloo was on the right track in seeing architecture as a field of critical and cultural speculation, rather than just a technical field," he says."

On September 7, 1979, Architecture’s renowned Rome program for fourth-year students was introduced. On the same September date 25 years later, the first class was held in the school’s new home in Cambridge. Situated along the banks of the Grand River, the former Riverside Silk Mill building provides open spaces for design studios, labs and classrooms.

Haldenby says while the school was still in Waterloo, it had become the leading school of architecture in the country, but had some of the worst facilities.

In the late 1960s, the school became part of the Faculty of Environment and eventually relocated on campus into the Environmental Studies II building. As the success of the program grew, the classes became crowded and the design space cramped.

Before the school moved to its current home in Cambridge there was some resistance.

“There were people on campus who said that by moving we’d lose our edge,” Haldenby says. “I responded that with better facilities we could do more things, especially in our graduate program. Our students have expanded the bounds of what we think is architecture in a way I would never have imagined.”

The School of Architecture's current home in Cambridge, Ontario.

In 2004, The School of Architecture returned to its roots as part of the Faculty of Engineering after 36 years in Environment. Today, the school is an international leader in design education and research. It offers a fully cooperative professional program and is ranked as having the greenest architecture curriculum in Canada.

The competition is stiff for Waterloo’s undergraduate Architecture program that attracts top students from around the world. This year, a panel of faculty members and students interviewed 450 applicants, culled from well over 1,000, for just 77 first-year spots.

Anne Bordeleau, the current director of the School of Architecture, says she’s impressed with the students’ openness and their willingness to learn.

“They’re creative people who understand there’s not just one solution to the problems they may encounter,” she says.

An architect and historian who has been a professor at Waterloo since 2007, Bordeleau believes the best way of teaching architecture is within a full cultural context.

"It is about opening their eyes rather than just honing in on disciplinary skills," she says. "We are trying to help develop critical thinkers and encourage students to become active citizens of the world."

One way students have expanded on what they’ve learned in the classroom has been through their involvement in the Venice Architecture Biennale, the largest and most important international architectural exhibit. Waterloo Architecture faculty members have curated exhibits at four of the past five biennales – an unparalleled feat.

One way students have expanded on what they’ve learned in the classroom has been through their involvement in the Venice Architecture Biennale, the largest and most important international architectural exhibit. Waterloo Architecture faculty members have curated exhibits at four of the past five biennales – an unparalleled feat.

Bordeleau says she’s impressed not only by the continued involvement of the school’s faculty members, but more particularly by how professors have made it their mandate to involve students in every project.

Piper Bernbaum was one of the students on the team that designed The Evidence Room for last year’s biennale. Led by Bordeleau and professors Robert Jan van Pelt and Donald McKay, the installation consists of all-white, full-scale, haunting models of the architecture of Auschwitz.

Waterloo Architecture students Alexandru Vilcu, Siobhan Allman, Anna Longrigg and Piper Bernbaum review the Auschwitz Crematorium Evidence Plans with professor Robert Jan van Pelt, second from right.

Bernbaum, who received the Governor General’s Gold Medal for a master’s student when she graduated last spring, was the installation and project manager of the expanded exhibition of The Evidence Room that is on display until early next year at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. Currently, she is teaching as an adjunct faculty member for the school’s Rome program.

“The strong feelings I have for the school and great gratitude for the enormous opportunity and encouragement the faculty has given me, is shared among many alumni who after completing their degrees, continue to come back and be involved in the school community,” says Bernbaum. “The school spirit dominates in what has been an amazing 50 years of collective support and exploration.”

Read more

Here are the people and events behind some of this year’s most compelling Waterloo stories

Read more

Waterloo Engineering community honours impact and innovation at annual awards dinner

Read more

Meet five exceptional Waterloo graduate students crossing the convocation stage as Class of 2025 valedictorians

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.