Ourotech developing biomaterials for testing of cancer drugs

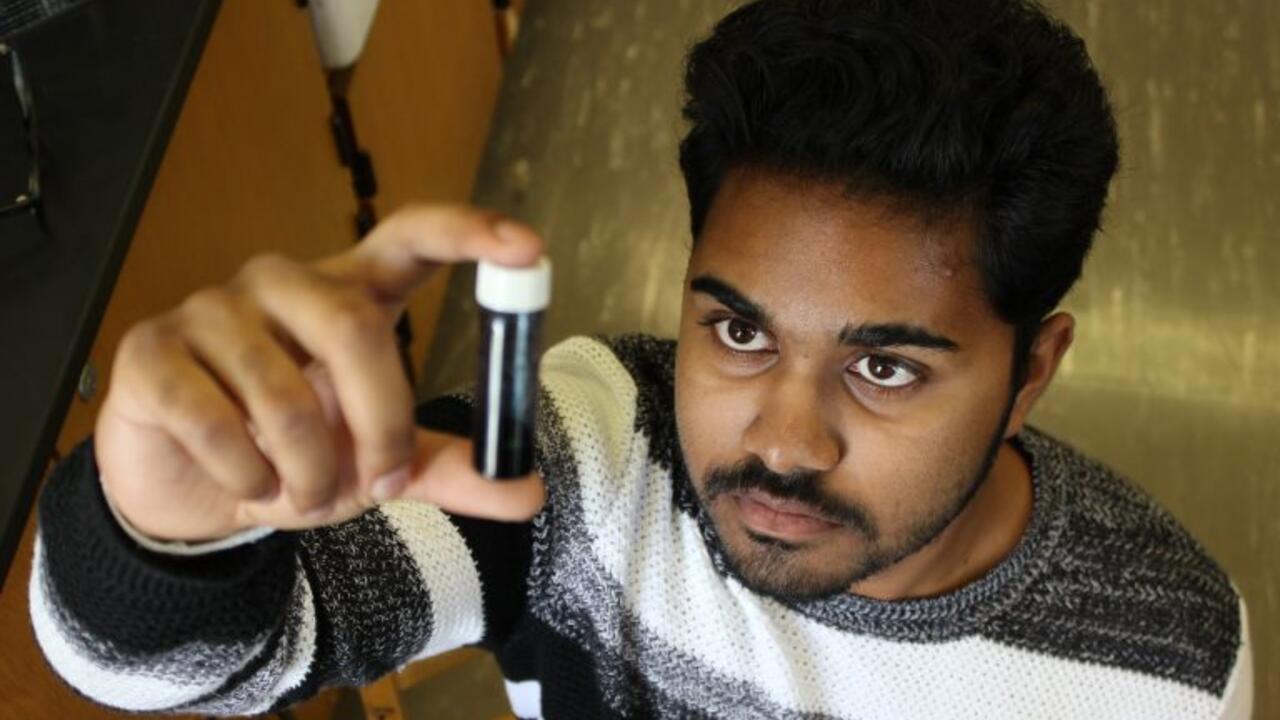

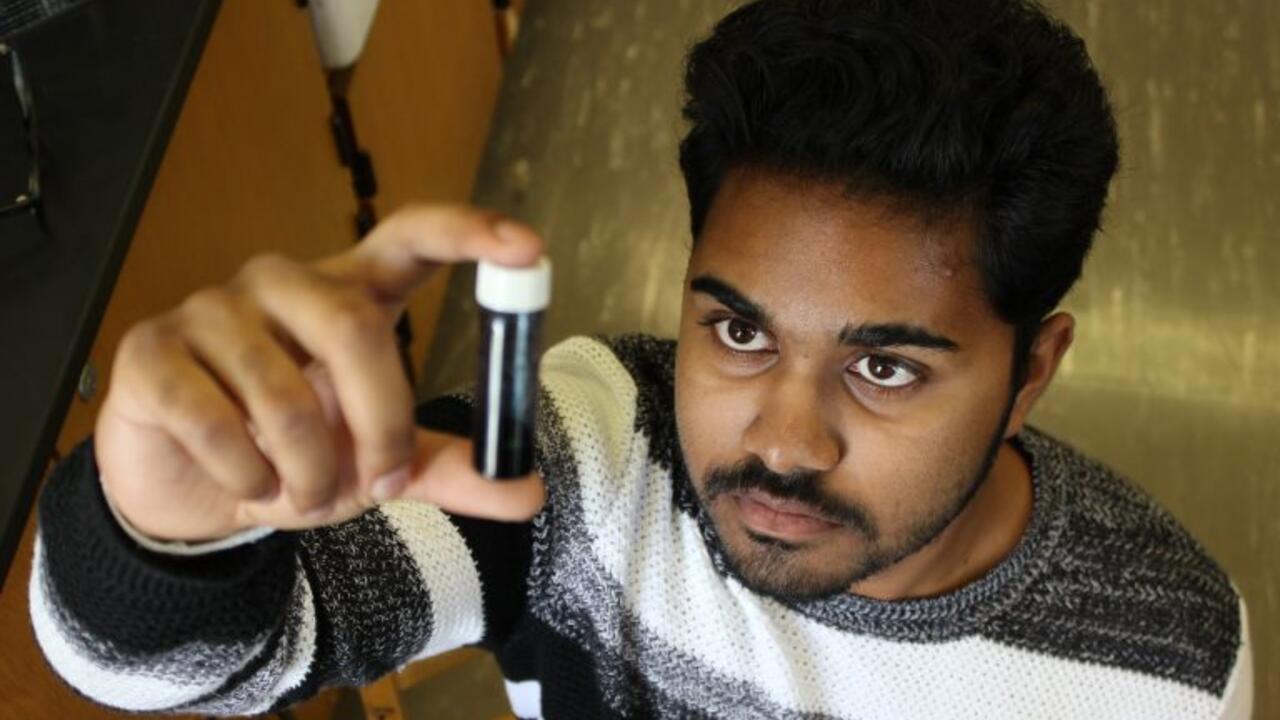

Duleek Ranatunga and the Ourotech team walked off with a $50,000 prize at the Wolves Summit last year

Duleek Ranatunga and the Ourotech team walked off with a $50,000 prize at the Wolves Summit last year

By Shane Schick Faculty of EngineeringDuleeka Ranatunga proved the strength of his belief in his business idea when he entered – and won – a startup competition known as the Wolves Summit last year.

Held biannually in Warsaw, Poland, the contest is widely celebrated as a gathering of engineers, designers and other innovators. It’s also an opportunity for entrepreneurs to get in front of investors to make five-minute pitches.

When Ranatunga went to pitch Ourotech’s soft-tissue printer, he knew the competition was going to be stiff.

“The stats were against us, but I did bet my savings on it to go to Europe to pitch it, so I was definitely hoping,” he says. “It was $3,000 for the trip, plus I had to pay for the conference ticket, hotels.”

The gamble paid off and then some. Up against more than a hundred startup companies from across Europe, the only Canadian entry walked off with a $50,000 prize.

Since then, Ourotech has evolved both its product and the value proposition it brings to the medical sector.

While still in a University of Waterloo research lab in 2014, Ranatunga was working with hydrogels and hoping to use them to make orthopedic soles. Later, he started experimenting with 3D printing and hydrogels to make artificial organs for use by surgeons practicing difficult procedures.

After returning home victorious from Poland, however, the Ourotech team began to realize an even more unique opportunity.

“I was getting a lot more into cancer research, and I found that we can actually use these hydrogels we were working with to make tumors,” Ranatunga says. “We basically take cancer cells from patients and put them into the biomaterials to make the tumors. We can then use those tumors to test cancer drugs.”

The innovation is important because 94 per cent of drugs that pass in animal testing go on to fail during human trials. He says that costs pharmaceutical companies up to $400 million per failed drug due to unnecessary human trials.

Ourotech aims to streamline the testing process by providing researchers with patented biomaterials mimicking parts of the human body.

“Mostly what we’re concerned with is copying things with the PH or oxygen ingredients found in human tumors,” he says. “We can fail drugs that don’t work in that kind of environment, even if they work in animal testing.”

It’s not uncommon currently to do tests on 1,000 animals, usually mice, in a single project. With its models using biomaterials, Ourotech can help researchers reduce the number of tests by half.

In addition to increasing accuracy, Ourotech projects that pharma companies could save 40 per cent on drug-testing costs because its models are only one-fifth as expensive as a single mouse.

The company, which includes a team of five full-time employees, is currently manufacturing its product and by next year expects to be focused on sales.

As he helps lead Ourotech to its next success story, Ranatunga credits the University’s nanotechnology engineering program with getting him off to a great start.

“The research I did in co-op is what helped me a lot,” he says. “The education was the fundamental building block, especially with the chemistry and biology.

“We have something the animals can’t replicate. You can fail drugs earlier, before doing human or animal testing, because we’re testing something that mimics the human body.”

Read more

Here are the people and events behind some of this year’s most compelling Waterloo stories

Read more

Meet the five exceptional graduate students taking the convocation stage as Class of 2024 valedictorians

Read more

The Government of Canada announces funding for discovery and applied research in engineering, natural sciences, health and social sciences

Read

Engineering stories

Visit

Waterloo Engineering home

Contact

Waterloo Engineering

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.