Artistic careers by design

Two Architecture alumni are fulfilling their artistic passions in unique ways

Two Architecture alumni are fulfilling their artistic passions in unique ways

By Carol Truemner Faculty of EngineeringWhether it’s creating a mural in a public space or building a tiny mobile home, two Waterloo School of Architecture alumni are fulfilling their artistic passions in unique ways.

Stephanie Boutari (BArch ’11 and MArch ’14) and Adam Schwartzentruber (BArch ’11) chose to study architecture not knowing where it would lead, but driven by a common desire to pursue a creative career.

After Boutari completed her undergraduate degree, she worked for a Toronto urban planning firm for a year before returning to Waterloo to begin a master’s in architecture.

It was when she started her graduate thesis that Boutari decided to take her artistic talents in a different direction.

“I began looking at the use of colour in architecture and exploring it physically, not just writing about it,” she says. “I became interested in testing the architectural effects of paint.”

As luck had it, there was a building across from Waterloo’s School of Architecture on Melville Street in Cambridge that Boutari thought would make a great canvas.

Boutari contacted the owner of the building, who provided her with the required permissions to paint a mural.

“He was on board and even offered to cover the cost of the materials,” Boutari says. “In his mind, it was a beneficial thing to have art there to deter graffiti and vandalism.”

Boutari’s concept for the mural was to create visual depth on the building’s flat surface by painting geometric forms that appear to be recessed within the wall.

“From a distance, it kind of looks like abstract windows,” she says.

Stephanie Boutari painted her first mural on the outside wall of the Bread Factory located across from Waterloo’s School of Architecture.

After finishing her first mural, Boutari started another as part of her thesis and this time it was a paid commission. She worked on several paintings before embarking on an installation at the School of Architecture’s gallery. The completed design allowed visitors to inhabit a mural ‘room’ as the painting covered three walls and the floor of a semi-enclosed area.

“I painted a line pattern that covered the room’s walls and floor so that if you stood at a specific point it created a perspective illusion, making the walls on either side effectively disappear into the back wall,” she says. “Then on the opposite side of the room, you could see a projected video of how it was created so you really see the contrast.”

After graduating with her master’s degree, Boutari returned to Toronto, where she worked for a company that specializes in interior design, architecture and fabrication.

She spent her weekends working on mural commissions in the Waterloo area, including one at the Settlement Co. coffee shop and another at Abe Erb brewpub, both in Kitchener.

“Both were really good exposure for me because those places are popular," she says. "As a result, I got more requests for murals.”

In June 2017, Boutari took a leap of faith and quit her job to pursue art full-time.

One of the first projects she worked on after leaving her Toronto position was a live art project to spruce up Goudies Lane in downtown Kitchener.

Sponsored by Kitchener’s Business Improvement Association, the project’s goal was for the four participating artists to transform a bleak space into a bright and colourful pedestrian walkway where people could enjoy a coffee, eat lunch or hold events.

“I came up with a design ahead of time and made sure I could execute it in the time given,” she says. “I wanted to create something really bold and bright that would look three-dimensional and appear as if it’s folding.”

As part of an art project to spruce up Goudie’s Lane in downtown Kitchener, Stephanie Boutari created a mural that looks three-dimensional.

At the beginning of the show, people questioned Boutari about what she was doing. By its end, many were not only liking her geometric design on social media, but were using it as a backdrop for photos.

“That engagement is what I want public art to do,” she says. “The success of using art to help rejuvenate a neglected public space is exactly why I got into this in the first place.”

Her career, which has flourished since the Goudies Lane art project, includes mural work for Miovision and North Inc., both founded and owned by Waterloo Engineering alumni.

Stephanie's mural for MiovisionStephanie Boutari has completed murals for companies founded by Waterloo Engineering graduates, including Miovision.

Along the way, Schwartzentruber, who Boutari began dating as an undergraduate student and married in 2013, has helped with the installation of her work.

Schwartzentruber completed two years of physics at Waterloo before transferring into architecture to join Boutari’s class.

He admits that he didn’t always follow the program’s studio rules, which was something Architecture Professor Philip Beesley not only noticed, but encouraged.

Impressed with Schwartzentruber’s approach to architecture, Beesley offered him a co-op position with his firm Philip Beesley Architects, which specializes in the architectural design of public art and experimental installations.

“It was really kind of funny because I didn’t know my theoretical approach to studio projects was very much in line with Philip’s firm and practice,” he says.

Schwartzentruber spent three consecutive co-op terms working for Beesley and joined his firm after graduation.

“During that time I got to install sculptures all over the world for him,” he says. “It was a really good gig, but very atypical as well.”

Like Boutari, Schwartzentruber eventually returned to Waterloo for his master’s in architecture. As part of his program, he opened Boko, a creative design studio located behind a small plaza in New Hamburg.

“The basic goal of the studio was to learn by experience rather than by research,” he says. “It was kind of like a counter-thesis essentially.”

Instead of completing his graduate studies, Schwartzentruber began working full-time at Boko, of which Boutari is now a partner.

He describes the studio as “kind of a playground.”

“The slogan for Boko in the past was ‘anything and everything’ and it really has been,” he says.

Projects Schwartzentruber has worked on range from building a tiny 4.88-metre-by-2.7-metre house to creating custom-built ice cream carts as well as a tasting room for Kitchener’s Four All Ice Cream owned by Ajoa Mintah, a Waterloo chemical engineering alumnus.

In front of one of Boutari’s murals at Kitchener’s Settlement Co., hanging from the double-height ceiling is Schwartzentruber’s installation of an original Volkswagen Beetle that appears to be exploding.

Adam Swartzentruber puts finishing touches on a reclaimed window wall he built and installed for the new Settlement Co. in Ayr Ontario. Photo by Caitlin McWilliams

Schwartzentruber, who grew up outside of Wellesley, Ontario, and Boutari, who was born and raised in Bahrain, off the coastline of Saudi Arabia, frequently collaborate with each other on a variety of projects. Despite working together, their creative styles are different.

“We’re very opposite in some ways,” says Schwartzentruber. “She’s much more regimented and organized and I’m much more dreamlike and all over the place.”

While embracing the directions their careers have taken, the couple say their time spent as architecture students has greatly influenced where they are now.

“I feel like I learned a lot from all of the steps that brought me here and that my time at the School of Architecture has shaped the way I approach art,” says Boutari.

Top banner photo by: Sharon Mendonca

Read more

Redefining capstone learning by bringing students, faculty and community partners together to tackle real-world challenges

Read more

Here are the people and events behind some of this year’s most compelling Waterloo stories

Read more

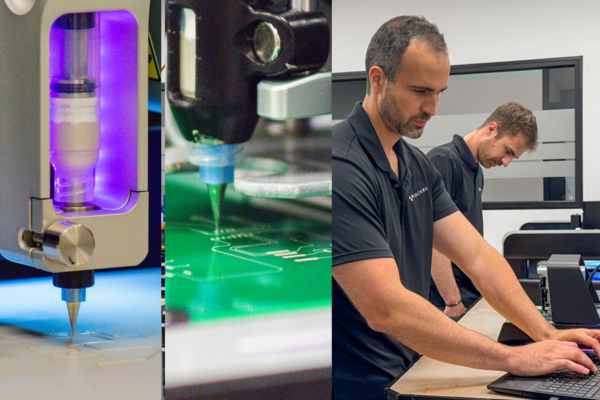

Voltera prints electronics making prototyping faster and more affordable — accelerating research to market-ready solutions

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.