Tiny technology to prevent the risk of skipping a beat or worse

A small blood monitor, about the size of a typical cell phone, could someday be all that stands between life and death for a cardiac patient

A small blood monitor, about the size of a typical cell phone, could someday be all that stands between life and death for a cardiac patient

By Kira Vermond Faculty of EngineeringA small blood monitor, about the size of a typical cell phone, could someday be all that stands between life and death for a cardiac patient.

Patricia Nieva, a mechanical and mechatronics engineering professor, is leading an international team of experts in creating a handheld monitor that could predict a heart attack in minutes, hours or even days before it happens.

Much like a glucose monitor that requires a diabetic to prick a finger and insert the test strip into a device for a reading, Nieva’s heart attack monitor goes even further: it would wirelessly and instantly relay test results to the person’s doctor. A cardiologist would then decide if an ambulance should be called.

With a hospital in India lined up for testing, and doctors and biomarker specialists at McMaster University weighing in, Nieva, who has a patent on the technology, is ready to build a prototype.

“The device will save the health industry a lot of money and will also give a sense of ease to those living with heart disease,” she explains.

She makes a good case. Today throat and chest pain is the second most common reason for emergency room visits in Canada, after abdominal and pelvic pain.

When someone goes to the hospital complaining of potentially life-threatening cardiac symptoms, they’re often hooked up to an electrocardiogram (EKG) machine and blood is taken to be tested for heart-related biomarkers to catch or rule out a heart attack. Waiting for results can take time, however, and that means emergency departments become clogged with waiting patients.

While Nieva’s cardiac blood test monitor works roughly the same way – it tests for an elevated level of a biomarker called cardiac troponin I – patients can wait at home.

The monitor could be especially useful for female cardiac patients who rarely experience typical men’s “Hollywood heart attack” symptoms: clutching the chest and a sudden collapse. Those who experience more common women’s symptoms including mild chest pressure, chills and nausea, would likely feel more comfortable testing themselves at home rather than rushing to the hospital on a hunch.

Nieva, who directs the University’s Sensors and Integrated Microsystems Laboratory, says the project combines her own background in sensors with her physician father’s interest in cardiology. Yet the technology has a wide reach that encompasses her other research involving automotive car batteries.

Nieva says she’s able to explore such innovative ideas with life-changing potential because Waterloo Engineering encourages entrepreneurism with real world impact. The fact that she owns her intellectual property rights is a huge bonus not just for her own research, but for her students’ as well.

One of her graduate students, Ryan Denomme, even launched a spinoff startup company out of her lab. His company Nicoya Lifesciences focuses on building low-cost and accessible diagnostic tools.

“I think this happens only at Waterloo. It’s unique.”

“We have the freedom to be able to have an idea and develop it. And sometimes those ideas even save lives.”

Read more

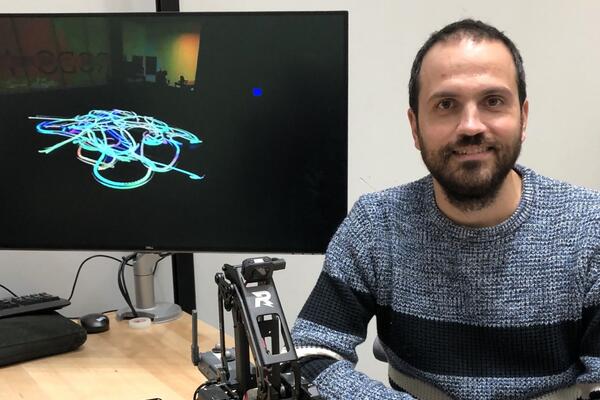

Robots the size of a soccer ball create new visual art by trailing light that represents the “emotional essence” of music

Read more

Waterloo prof leads a team of researchers to improve water quality through a community-focused approach underpinned by technical excellence

Read more

New medical device removes the guesswork from concussion screening in contact sports using only saliva

Read

Engineering stories

Visit

Waterloo Engineering home

Contact

Waterloo Engineering

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.